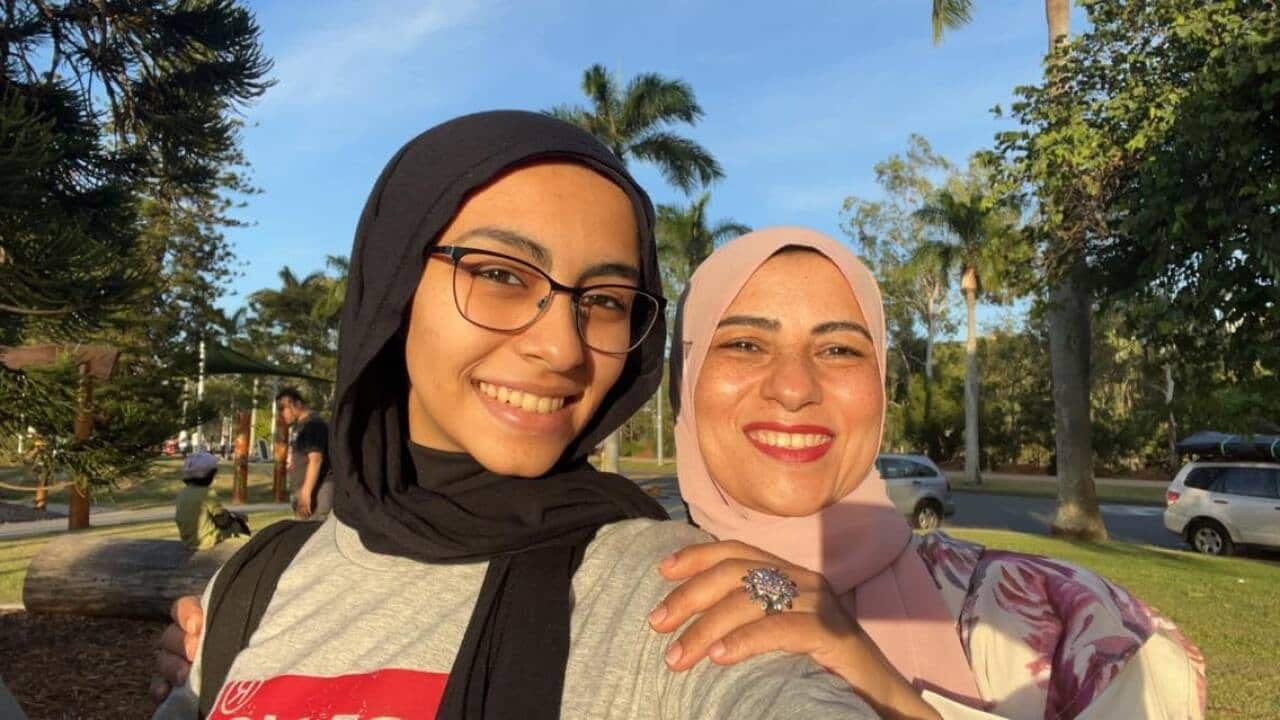

Sanaa* (not her real name), 43, got a divorce 12 years ago but for most of those years, her four children lived with her ex-husband.

“It was hard, but I didn’t have the financial means to support them,” she said.

“I had to get a job and find my feet first.”

Sanaa had two children under the age of five at the time of divorce.

Despite lacking financial stability, Sanaa, who has been living in Sydney, chose not to seek a property settlement.

“‘Disgust’ is the word that describes best how I felt. I felt disgusted at the idea that I needed money from someone.

“I didn’t want my ex to come to me one day and say, ‘you took my money’. I’d rather be wronged than wrong someone.”

In Australia, if a couple cannot decide how their property can be divided after divorce, it is left up to the family court to decide.

But some Arab women are made to feel uneasy about taking a share of the wealth and assets accumulated during marriage.

The reasons are often a mixture of culture and religion.

'Religious excuses’

According to the research paper , sharing property between spouses has long been a controversial subject among Muslims in particular.

Authored by two lecturers in Sharia and Law at Malaysia's Universiti Islam Antarabangsa Sultan Abdul Halim Mu’adzam Shah, the study says that many Islamic scholars believe that splitting wealth after divorce “contravenes what the Shariah has dictated, regarding an independent financial responsibility for both spouses”.

The Council of the International Islamic Fiqh Academy (IIFA) issued a in 2018 stating that “each spouse property, whether resulting from the marriage contract or other reasons, is considered personal property of its owner and will”.

The fatwa adds that “there is no Shariah prohibition if the spouses mutually agree to share their properties based on consent and personal choice”.

However, the council’s opinion slightly departs from the orthodox stance by explaining that upon divorce the wife has the right to resort to court to claim compensation for “losses that affected her” during the marriage.

Dr Ibrahim Abu Mohamad, Mufti of Australia, echoes a similar opinion.

“A wife who has contributed to augmenting the family’s wealth has the right to ask for a share of it upon divorce,” he said.

However, some within the Arab community still refer to religion to discredit women who seek a share of matrimonial property after divorce.

“Even if a few people support her, the rest of the community would accuse her of doing an injustice to her ex-husband,” Sanaa said.

“Religious excuses are definitely used against women in this case.”

Lawyer Hashim al-Hosseini explains that Australian law does not differentiate between men and women.

“The distribution does not favour women over men as it is perceived sometimes.”

“It all depends on each partner’s contribution to the wealth, be it direct or indirect,” he added.

Because Arab women, especially in the older generations, are mostly the ones who forgo work outside the home to care for family, they are, according to al-Hosseini, seen as “undeserving” of a share of mutual wealth.

“We grew up in a culture where men don’t appreciate housework and they do not see it as equal to working outside the home. This form of unpaid work is taken for granted,” he said.

“The partner who is staying at home and looking after the house and the kids is enabling the other one to work outside and advance their career,” he added.

Credit: Unsplash

“If he had hired someone to do all those chores all those years, he would’ve paid them a fortune,” he said.

Making a case for cultural specificity

Some Arab men, however, think that what works for the Australian larger society does not necessarily work for the Arab community where the division of roles and responsibilities within the family is different.

“Arab men are the breadwinners and based on religion, tradition and culture, they are the ones fully responsible for supporting the family financially. Even if the wife works, her financial contribution is optional and minimal,” said Mohamed Hamdy, an Australian Egyptian who has been living in Sydney since 2016.

“It is not like with Western couples where family expenses are split between the two partners equally,” he added.

Kamal Moussa, who makes YouTube to help Arabic-speaking viewers migrate to Australia, reiterated the cultural specificity argument.

“My wife works, but her income is used for her own personal expenses. She contributes to household spending from time to time, but her contribution would never be 50 per cent,” he said.

Therefore, both Hamdy and Moussa believe it is “unfair” to the husband to have to give up a share of his wealth to his ex-wife after spending so much money during the marriage.

“The wife might be the one who ends up accumulating more wealth because of the lack of financial responsibilities,” explained Hamdy.

Popular misconceptions

There is a popular perception within the Arab community that there is a 50-50 split rule of wealth in case of divorce.

But al-Hosseini explained that it is not that simple since a variety of factors must be considered.

“As per the law, there is no strict formula for a divorce financial settlement in Australia,” he said.

“It varies from one case to another.”

And when religion is thrown into the formula, divorce among Muslim couples in Australia becomes even more complicated.

Traditionally, Islamic law does not recognise the concept of marital wealth.

Islamic law, however, gives women specific financial entitlements upon divorce.

Therefore, in addition to following the Australian divorce law, a couple may also need to decide how Islamic law applies in their situation.

IIFA’s describes recoursing to court as a “contemporary activation” of the spouse’s financial entitlements specified by Islamic law.

If he ever gets a divorce, Kamal said Islamic law would be his reference.

“A couple can do their own informal agreement based on shari’ah,” he explained.

Credit: Moment RF/jayk7/Getty Images

‘Mix and match approach’

When Sanaa divorced her husband, she received her financial entitlements based on Islamic law, but it did not help much.

“It was a small amount of money. I went through financial difficulties for sure,” she explained.

Dr Abu Mohamad says that after 20 years of marriage, for example, the amount of money specified in the marriage contract would probably be insignificant.

“In some of the mediation cases I was involved in, the amount of money the husband owed the wife based on the marriage contract was less than 100 dollars,” he said.

“It should be calculated against a fixed reference, such as gold, for example,” he added.

Ruba (not her real name), a mother of three who got a divorce six years ago, failed to get a share of the wealth accumulated during her marriage because her ex-husband hid his property in his home country.

“I had no documents to prove it,” she said regretfully.

She is happy she had been working all along, which saved her from falling into financial distress.

Ruba thinks the problem is that some Muslim couples approach divorce with “a mix-and-match logic”.

“People want to use a mixture of Australian law and Islamic law to their advantage,” she explained.

“They should stick to one or the other.”