Disclaimer: This article discusses Aboriginal deaths in custody, which may be upsetting for some readers. It also contains the names and images of Aboriginal people who have passed.

Australia is not one country. It’s two.

We are split along racial lines as surely as South Africa was during the era of apartheid.

It may sound like hyperbole but it is a fact.

In 2018, an Australia-first report card on levels of institutional racism in Queensland’s health system found that ten of the state’s 16 Health and Hospital Services (HHS) scored ‘very high’ levels of institutional racism, and the remaining six, a ‘high’ level of institutional racism.

In over 20 years of working as a human rights lawyer it is my observation that the Queensland experience is common to most, if not all, states and territories.

The racial divide that I see means that most white people lead lives of privilege whilst Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders are shunted aside, told that they do not really matter, and they face prejudice at every turn.

The focus recently has (rightly) been on Black deaths in custody. But what of the role that prejudice in the health system plays in Indigenous deaths.

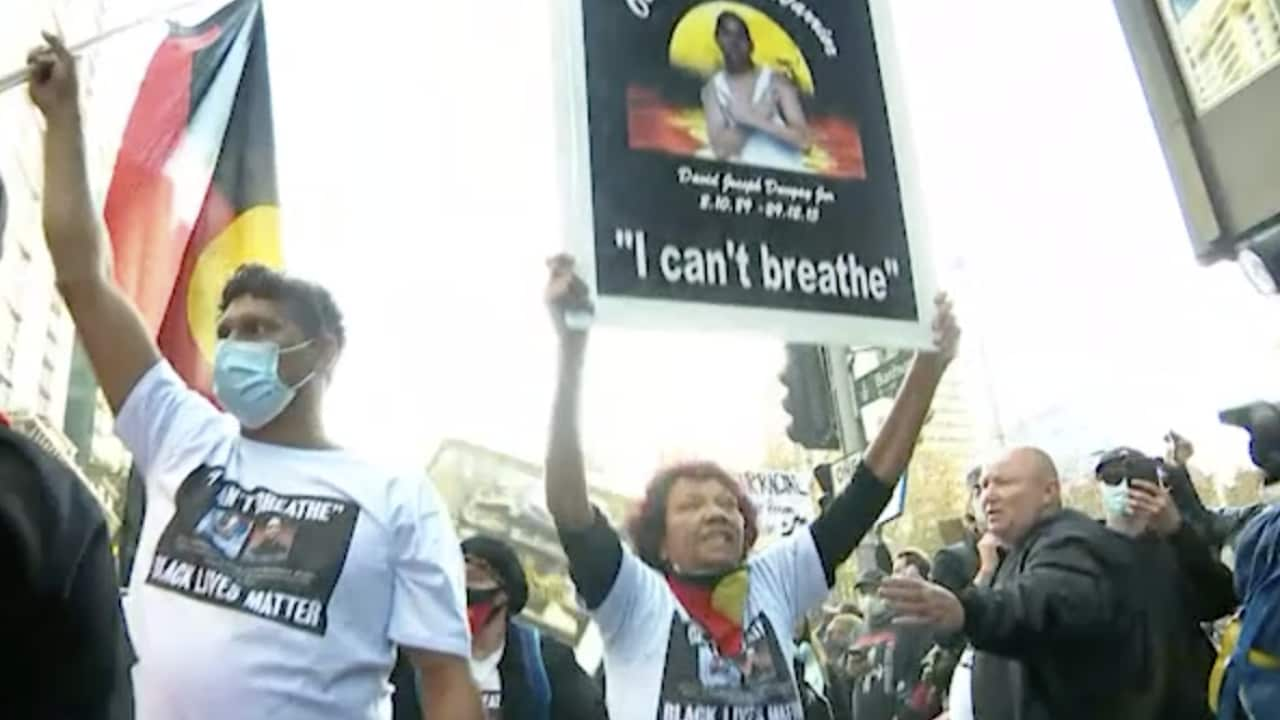

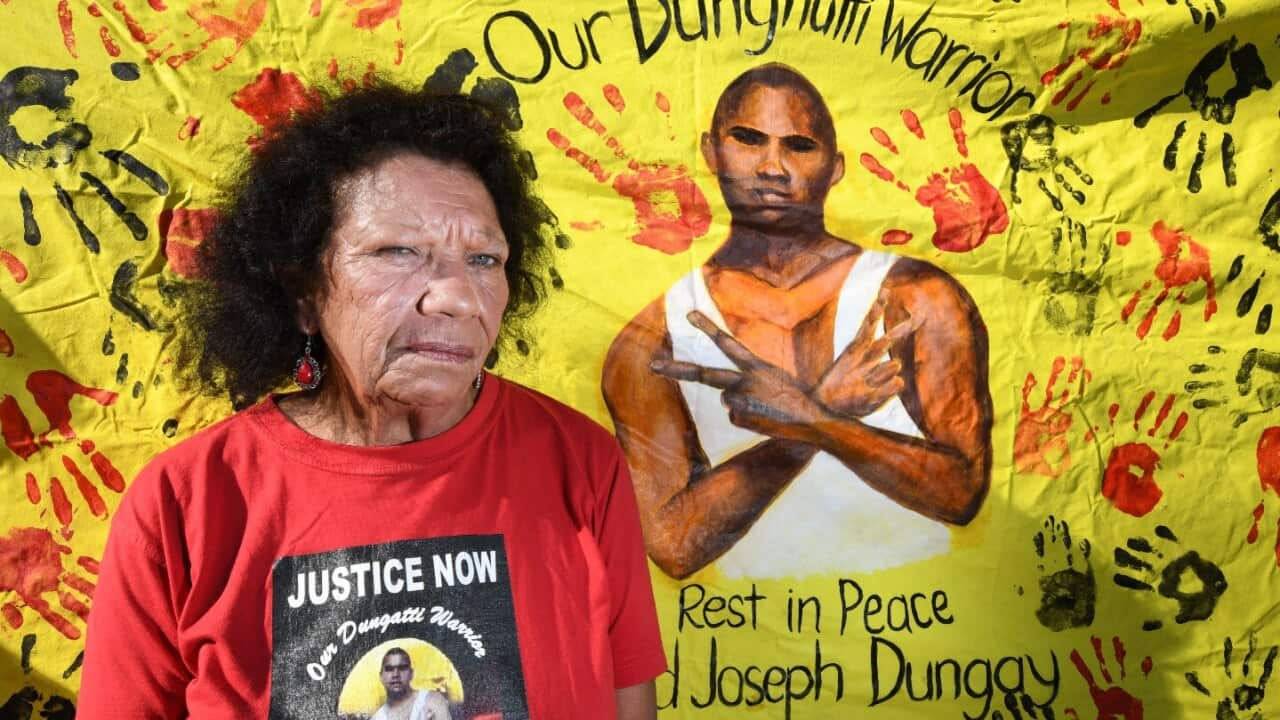

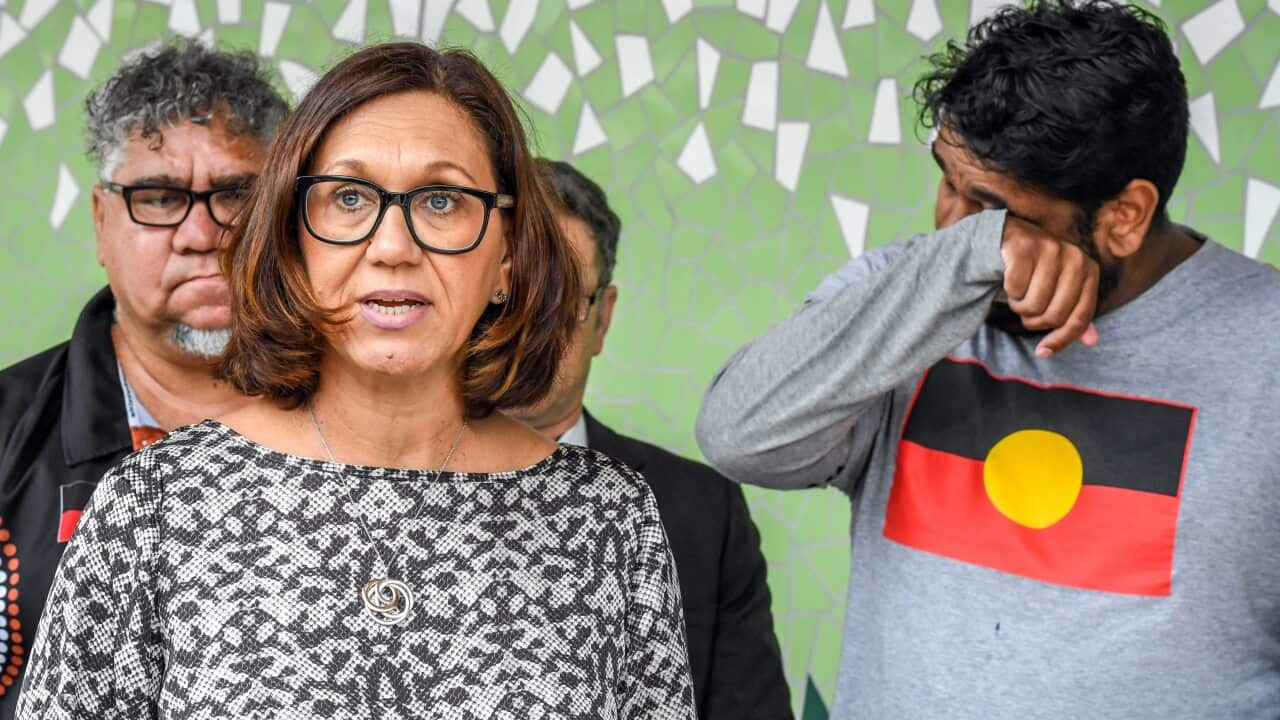

The connection between George Floyd and David Dungay Jr highlights the similarities between state violence in the USA and in Australia but does not reveal the role that racial bias in health care plays in Indigenous deaths and injuries.

Most Australians are unaware that David Dungay Jr died in a prison hospital.

NSW is the only Australian state or territory that has a hospital inside a jail.

David Dungay’s death exposed the dysfunctional relationship between prison guards and health professionals in that strange environment. During the course of the inquest into David’s death it became obvious that prison guards, without any medical training, tried to get involved in the management of David’s psychiatric and diabetic issues, by using the bluntest tool at their disposal - the prison’s Immediate Action Team, a special team of guards well-trained in the use of force but not positional asphyxia.

Additionally, prejudice in health care is said to have contributed (in recent years) to the deaths of at least three Aboriginal women Ms Dhu, Naomi Williams and Shona Hookey.

In Ms Dhu’s case, despite suffering osteomyelitis, septicaemia and pneumonia, police, clinicians and health workers appear to have engaged in a negative feedback loop of stereotyping and prejudice that was conveyed back and forth from police to health workers which contributed to her death.

The WA State Coroner was told that at least some of this behaviour could be explained by heuristic thinking, a form of mental shortcut or cognitive bias, which may have led to the failures that ultimately killed Ms Dhu.

Related Reading

Ms Dhu's family opens up about the aftermath of her death

Shona Hookey was a young Aboriginal woman who died at Campbelltown Hospital in excruciating pain as a result of a twisted bowel. She suffered from a severe intellectual disability.

The NSW Deputy State Coroner was so concerned about the evidence of discrimination against Shona Hookey by a treating doctor that he referred him to the Health Care Complaints Commission for investigation.

Like Ms Dhu, Naomi Williams was suffering from septicaemia. She was sent home from Tumut Hospital with two Panadol tablets.

A few hours later, she was dead.

In her case, the NSW Deputy State Coroner also found that Naomi’s low expectations of Tumut Hospital affected her decisions in relation to her medical care in the days and hours before her death because she felt unheard, she felt stereotyped as a drug user, she felt unsafe and was planning to have her baby elsewhere because she wasn’t receiving adequate treatment.

The Coroner said that those concerns were legitimate.

In Naomi Williams Inquest the NSW Deputy State Coroner made a range of recommendations to address prejudice and bias in health care. They echo equally across all of Australia and include:

1. Strengthening the Aboriginal Health Liaison Worker programme and making it operate 24/7

2. Adopting Targets for the employment of Aboriginal health care professionals

3. Auditing Implicit Bias/Racism and recording statistics

4. Identifying and using assessment tools to measure implicit bias

5. Establishing targets for proportional representation of Aboriginal people on local health boards and Advisory committees

6. Ongoing and meaningful consultation with key Aboriginal health groups

7. Investigating strategies to develop culturally appropriate care

The 1991 Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody recognised health as a key factor in custodial safety but more importantly they recognised that “Many non-Aboriginal health professionals at all levels are poorly informed about Aboriginal people, their cultural differences, their specific socio-economic circumstances and their history within Australian society” and that negative stereotyping of Aboriginal People is not uncommon in health care.

Systemic prejudice and discrimination exist across all of Australian society. That it exists in our health care system is not just shocking, but also leads to the ongoing death, misery and suffering of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

We are all born equal with a fundamental right to equality in health care. That right must be respected.

Until we acknowledge that discrimination and prejudice contribute to the gap in the health outcomes across our nation and we start to address those evils, we cannot stop our campaign to demand health justice.

George Newhouse is the CEO of the National Justice Project, a not-for-profit legal service and civil rights organisation dedicated to tackling systemic injustice, discrimination and racism. He is also an Adjunct Professor of Law at Macquarie University. To follow George on Twitter go to @GeorgeNewhouse

To hear more about these issues tune into Living Black: Aboriginal Lives Matter on SBS On Demand: