Convinced that racism and racist violence in the Australian community justified a strong response, the Labor government of Paul Keating pressed ahead with new laws to deal with racial hatred.

And in doing so, they launched a simmering controversy over one particular provision which outlaws any act which has the effect of offending, insulting, humiliating or intimidating another person or group.

That's better known now as Section 18C of the Racial Discrimination Act 1975, an amendment made in 1995 following a long period of public consultation. Cabinet papers for 1995, released on Monday by the National Archives of Australia, show that even then, there was widespread objection on grounds that this would impact free speech.

Cabinet papers for 1995, released on Monday by the National Archives of Australia, show that even then, there was widespread objection on grounds that this would impact free speech.

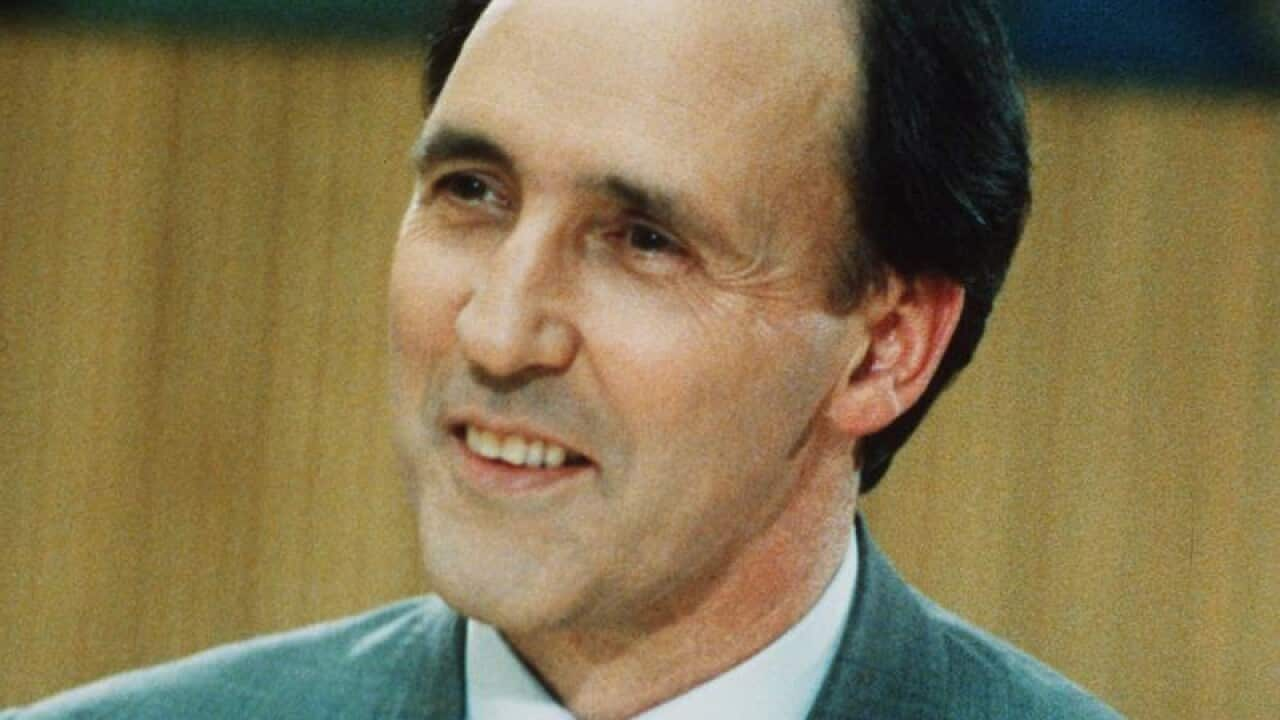

Paul Keating: Instrumental in passing the Native Title Act in 1993. Source: AAP

Labor government attorney-general Michael Lavarch said in his view none of the fears were well-founded and it would not affect the basic right of freedom of speech.

"That right is of course not absolute - there are already a number of restrictions on freedom of speech under existing law, for example laws on defamation and obscenity," he said in his submission to cabinet in October 1994.

"I believe the right to free speech must be weighed against the right of people from different racial backgrounds to enjoy their lives free from racial discrimination and hatred."

But however the government proceeded there would be strong criticism, Lavarch admitted.

That criticism and public debate about 18C and its effect on free speech surged in recent years, triggered by high-profile cases, such as that of journalist Andrew Bolt over two articles in Melbourne's Herald Sun newspaper. They were found reasonably likely to offend, insult, humiliate or intimidate fair-skinned Aboriginal people.

The Keating Labor government decided to proceed with a new Racial Hatred Bill after the original bill lapsed when parliament was dissolved for the 1993 election.

Lavarch said the public consultation process attracted more than 700 submissions, with fewer than 100 supporting the legislation.

"Many submissions received by my department expressed the fear that no-one will be able to do such things as make jokes about the Irish any more or go to see 'Wog-a-rama' if such sanctions apply and that the thought police would be able to visit people in their homes to see what they were saying and reading," he said.

Others thought existing state and territory laws were sufficient and that criminal sanctions wouldn't work.

Lavarch said inclusion of criminal sanctions was the most contentious aspect of the 1992 bill. He said he now favoured both criminal and civil sanctions.

"In my view the degree of seriousness of some instances of racism is such that there are strong grounds to enact both civil and criminal prohibitions," he said.

"Criminal sanctions will deter potential offenders and punish proven offenders in an exemplary fashion. Some groups in the community need special protection from threats, harassment, ridicule and contempt."

Lavarch stepped away from including ethno-religious hatred in the bill.

He said there were good reasons for anticipating this would be more rather than less divisive, protecting people who stood out on the basis of their religious dress.

In a draft speech to parliament, Lavarch said this law was intended to cover racist statements or propaganda of a serious and damaging kind.

He cited examples such as extremist groups letter-boxing leaflets accusing certain races of plotting to overthrow the government, public speeches calling for repatriation of ethnic groups or violence against ethnic groups.

With AAP