Hundreds of demonstrators protested in Shanghai on Sunday night as flared for the third day and spread to several cities in the wake of a deadly fire in the country's far west.

The wave of civil disobedience is unprecedented in China since assumed power a decade ago, as frustration mounts over his signature zero-COVID policy nearly three years into the pandemic. The COVID measures are also exacting a heavy toll on the world's second-largest economy.

Meanwhile, the BBC said a journalist covering the protest was assaulted by police.

"The BBC is extremely concerned about the treatment of our journalist Ed Lawrence, who was arrested and handcuffed while covering the protests in Shanghai," a spokesperson for the British public service broadcaster said in a statement.

"He was held for several hours before being released. During his arrest, he was beaten and kicked by the police.

"This happened while he was working as an accredited journalist."

Protesters in Beijing hold up white pieces of paper against censorship on 27 November. Credit: Kevin Frayer/Getty Images

Protesters also took to the streets in the cities of Wuhan and Chengdu on Sunday, while students on numerous university campuses around China gathered to demonstrate over the weekend.

In the early hours of Monday in Beijing, two groups of protesters totalling at least 1,000 people were gathered along the Chinese capital's 3rd Ring Road near the Liangma River, refusing to disperse.

"We don’t want masks, we want freedom. We don’t want COVID tests, we want freedom," one of the groups chanted earlier.

A protester gestures as he participates in a protest for the victims of a deadly fire as well as a protest against China's harsh Covid-19 restrictions in Beijing on 28 November. Source: AFP / NOEL CELIS/AFP via Getty Images

In a country where public criticism of the government is fraught, the protesters' condemnation of the regime is rare.

Why are people protesting?

Crowds took to the streets on Friday night in Xinjiang's capital of Urumqi, chanting "End the lockdown!" and pumping their fists in the air after a deadly fire triggered anger over their prolonged COVID-19 lockdown.

Ten people were killed and nine injured when the blaze ripped through a residential building in Urumqi on Thursday night, according to state news agency Xinhua.

In this image from a video, police, foreground, watch protesters in Shanghai on Saturday, 26 November 2022. Source: AAP / AP

Videos showed people in a plaza singing China's national anthem with its lyric, "Rise up, those who refuse to be slaves!" while others shouted that they wanted to be released from lockdowns.

On Sunday in Shanghai, police kept a heavy presence on Wulumuqi Road, which is named after Urumqi, where a candlelight vigil the day before turned into protests.

"We just want our basic human rights. We can’t leave our homes without getting a test. It was the accident in Xinjiang that pushed people too far," said a 26-year-old protester in Shanghai who declined to be identified.

Protesters light candles and leave cigarettes at a memorial for victims of a deadly fire during a protest against China's strict zero COVID measures. Credit: Kevin Frayer/Getty Images

By Sunday evening, hundreds of people gathered in the area. Some jostled with police trying to disperse them. People held up blank sheets of paper as an expression of protest.

A Reuters witness saw police escorting people onto a bus which was later driven away through the crowd with a few dozen people on board.

On Saturday, the vigil in Shanghai for victims of the apartment fire turned into a protest against COVID curbs, with the crowd chanting calls for lockdowns to be lifted.

“Xi Jinping, step down! CCP, step down!”, one large group chanted in the early hours of Sunday, according to witnesses and videos posted on social media, in a rare public protest against the country's leadership.

How significant are the protests?

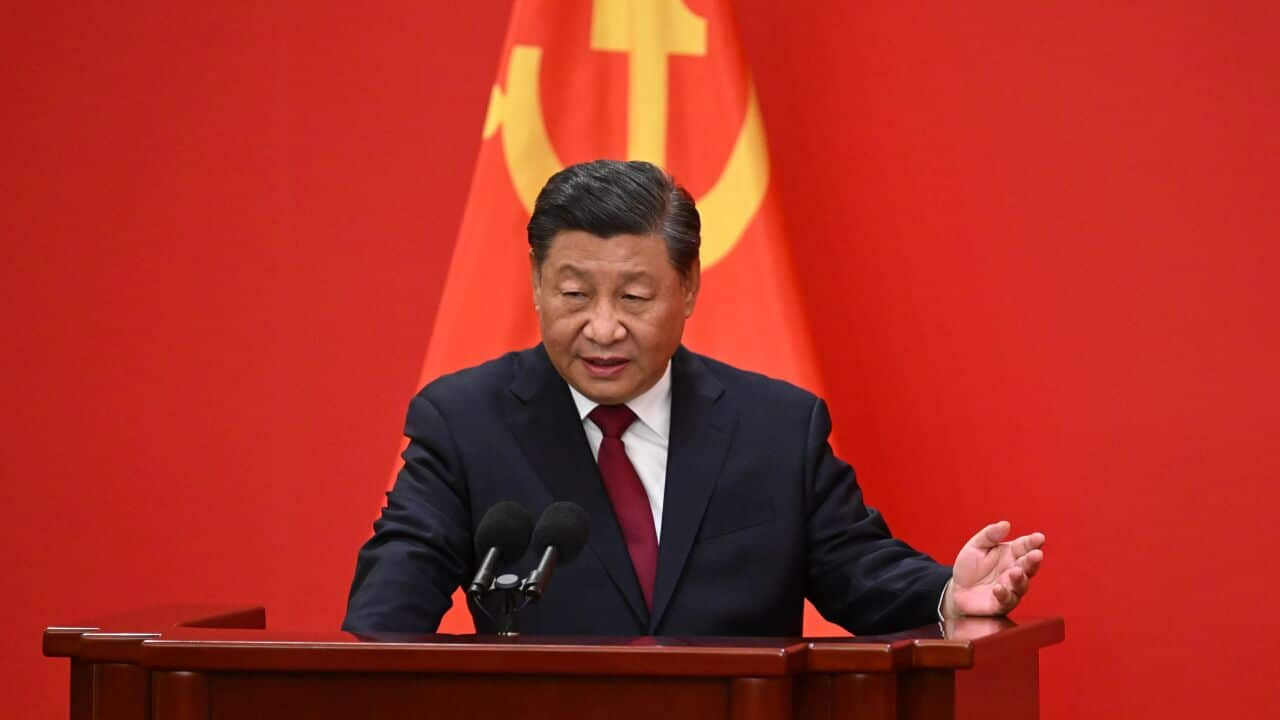

Widespread public protest is rare in China, where room for dissent has been all but eliminated under Xi Jinping — China's paramount leader — forcing citizens mostly to vent their frustration on social media where they play cat-and-mouse with censors.

Frustration is boiling just over a month after Mr Xi secured a third term at the helm of China's Communist Party.

"This will put serious pressure on the party to respond. There is a good chance that one response will be repression, and they will arrest and prosecute some protesters," said Dan Mattingly, assistant professor of political science at Yale University.

Still, he said, the unrest is far from that seen in 1989, when protests culminated in the bloody crackdown in Tiananmen Square.

He added that as long as Mr Xi had China's elite and the military on his side, he would not face any meaningful risk to his grip on power.

Richard McGregor, senior fellow of East Asia at the Lowy Institute said criticism of the ruling Chinese Communist Party is rare.

"It's very unusual to see protesters yelling out condemnation of the Communist Party and Xi Jinping,” he said.

“That’s something we have not seen for a long time.”

Mr McGregor said it would be difficult to predict whether the protest could lead to any change in policy.

“China is going into winter, they’ve got a lot of under-vaccinated people … the government officially is standing by COVID-zero ... but I think in many places — but not everywhere — there’s frustration with it," he said.

"So the question is whether the policy is changed or modified and whether we’ve seen the start of that."

China defends President Xi Jinping's signature zero-COVID-19 policy as life-saving and necessary to prevent the healthcare system from being overwhelmed.

Officials have vowed to continue with it despite the growing public push-back and its mounting toll on the world's second-biggest economy.

“I want to be careful of saying there’s a single public mood … but in some cities, there is a lot of anger and frustration about the policy and it seems to be reaching a tipping point," Mr McGregor said.

What has the official reaction been?

Urumqi officials abruptly held a news conference in the early hours of Saturday to deny COVID-19 measures had hampered escape and rescue, but internet users continued to question the official narrative.

Dali Yang, a political scientist at the University of Chicago, said the comments from authorities that the residents of the Urumqi building had been able to go downstairs and thus escape was likely to have been perceived as victim-blaming and further fuelled public anger.

"During the first two years of COVID, people trusted the government to make the best decisions to keep them safe from the virus," Mr Yang said.

"Now people are increasingly asking tough questions and are wary about following orders."

Reuters verified that the footage was published from Urumqi, where many of its four million residents have been under some of the country's longest lockdowns, barred from leaving their homes for as long as 100 days.

In the capital Beijing, 2,700km away, some residents under lockdown staged small-scale protests or confronted their local officials over movement restrictions placed on them, with some successfully pressuring them into lifting them ahead of schedule.

On Sunday, a large crowd gathered in the southwestern metropolis of Chengdu, according to videos on social media, where they also held up blank sheets of paper and chanted: "We don't want lifelong rulers. We don't want emperors," a reference to Mr Xi, who has scrapped presidential term limits.

In the central city of Wuhan, where the pandemic began three years ago, videos on social media showed hundreds of residents take to the streets, smashing through metal barricades, overturning COVID testing tents and demanding an end to lockdowns.

Other cities that have seen public dissent include Lanzhou in the northwest, where residents on Saturday overturned COVID staff tents and smashed testing booths, posts on social media showed. Protesters said they were put under lockdown even though no one had tested positive. The videos could not be independently verified.

At Beijing's prestigious Tsinghua University on Sunday, dozens of people held a peaceful protest against COVID restrictions during which they sang the national anthem, according to images and videos posted on social media.

China has stuck with its zero-COVID policy even as much of the world has lifted most restrictions. While low by global standards, China's case numbers have hit record highs for days, with nearly 40,000 new infections on Saturday, prompting yet more lockdowns in cities across the country.

Beijing has defended the policy as life-saving and necessary to prevent overwhelming the healthcare system. Officials have vowed to continue with it.

Why are Xinjiang and Shanghai in the spotlight?

Xinjiang is home to 10 million Uyghurs. Rights groups and Western governments have long accused Beijing of abuses against the mainly-Muslim ethnic minority, including forced labour in internment camps. China strongly rejects such claims.

Shanghai, China's most populous city and financial hub, which endured a two-month lockdown earlier this year, tightened testing requirements on Saturday for entering cultural venues such as museums and libraries, requiring people to present a negative COVID-19 test taken within 48 hours, down from 72 hours earlier.

This weekend, Xinjiang Communist Party Secretary Ma Xingrui called for the region to step up security maintenance and curb the "illegal violent rejection of COVID-prevention measures".

China is the last major economy wedded to a zero-COVID-19 strategy, with authorities wielding snap lockdowns, lengthy quarantines and mass testing to snuff out new outbreaks as they emerge.