You’re at home, switching off for the day by scrolling through your social media feed.

You come across a post about the Indigenous Voice to Parliament, and it stops you in your tracks. It’s emotive, and uses information you haven’t seen before.

Can you trust it? And what should you do with it?

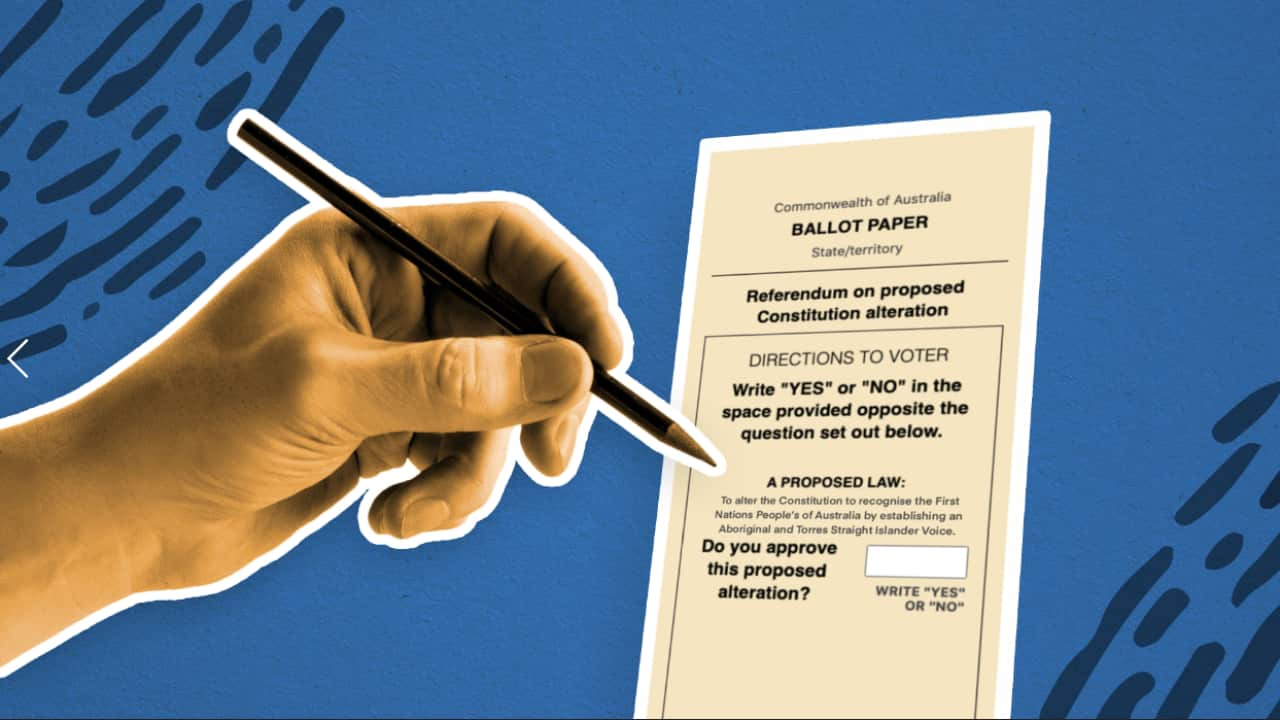

Experts are warning of an "incredibly large volume" of mis- and disinformation that is circulating in the referendum campaign, as Australians decide whether they will vote to enshrine an Indigenous Voice in the constitution.

In the lead up to voting day on 14 October, here’s what you need to know about identifying and engaging with potentially misleading content.

What is misinformation and disinformation?

Misinformation is generally defined as "false or misleading content or assertions" according to Timothy Graham, an associate professor in digital media at Queensland University of Technology who researches public communication on social media platforms.

When it comes to misinformation, he says "the person or the actor who's spreading them is not aware that what they’re doing is misleading or false".

"The difference between mis- and disinformation, in a traditional way, is really around intent. Was the person or actor aware of what they were doing? And what was the intention behind what they were trying to do?"

Ed Coper is the director of Populares, a communications agency that ran advertising for the major teal independent campaigns during the last federal election. He has also worked with GetUp and Change.org.

Coper has recently advised the federal government on dealing with misinformation and disinformation in the lead up to the referendum.

He said disinformation is more "pernicious" because it is deliberately spread by "people who know it to be false, who organise to deliberately fool people using false information lies".

Coper said it’s important to distinguish these types of information from political opinion, or the "normal cut and thrust of political arguments". "It is a spectrum," he said.

But Mathew Marques, a senior lecturer of social psychology at Melbourne's La Trobe University, says differentiating between mis- or disinformation can become complex.

"You would have to have a clear understanding of the intent of the person sending or spreading it, and that often can be hard," he said.

What about the Voice?

While it’s difficult to quantify in real terms, Coper said "there’s no doubt that on the Voice, we’re seeing an incredibly large volume of mis- and disinformation".

"It doesn’t take long, if you open up any social media platform and start looking for content on the Voice, to see that it appears the majority of it all looks very similar.

"It is all around the same types of lies and myths about the Voice."

When it comes to the voting process, these issues are also a constant battle for the Australian Electoral Commission (AEC), its commissioner Tom Rogers said last week, adding social media companies

Graham analysed 246,000 tweets about the Voice between March and May this year.

In a preprint paper published online this month, which is yet to be peer-reviewed, he broadly found that Twitter, now known as X, was then dominated by the Yes campaign in terms of tweet volume.

But the discourse was "marked by misinformation and conspiracy theories stemming from Vote No campaigners and further amplified by attempts to criticise and fact-check it from the Vote Yes camp".

How can I spot mis- and disinformation?

When you’re scrolling through social media, and you come across content that you’re unsure about, what should you do?

Marques said there are two key questions to ask yourself - what is the source, and how is the content being communicated to you?

"If you’re able, I would start off by checking the source of the information. For you, is it a trustworthy source? Is it likely to be an impartial source?"

Then, check whether the content has any "hallmarks of persuasive language" that might "draw you in".

Emotive language and 'knee-jerk reactions'

A common tool used in mis- and disinformation is emotive language.

"The use of emotive language is good at drawing people in, and making them feel something - whether that’s frustration or anger," Marques said.

"Negative emotions tend to carry more weight in terms of people’s attention to them."

Graham agreed. "When people are on social media browsing and they see content that gives them a really knee-jerk, strong emotional reaction, that’s often a sign that they need to step back and take some time to think about what’s being presented to them before acting on it," he said.

"Disinformation in particular is designed … to weaponise emotion, to get you not to think about the details… not to weigh up something that is a complex issue like this, but just to go, ‘yes I don’t want my land to be stolen'."

According to Marques, other elements to look out for include the use of "false dichotomies" or oversimplified arguments, and "scapegoating individuals".

"Attacking a person or a group, rather than debating or discussing the ideas, is another common tool that’s used," he said.

He encouraged voters to be aware of these tools and "try to drill down to the substantive content that is being put forward".

Coper said even understanding the types of tactics that are used will better equip people to recognise misinformation when they see it.

Verification and deliberation

Marques and Graham stressed the importance of verifying sources.

"One of the key dimensions to detecting and understanding mis- and disinformation … is around trying to understand where does this idea come from? What is the nature of the person or organisation that’s making this claim?" Graham said.

While this might take work, he argues responsibility lies with people who want to make informed decisions, particularly about the Voice.

Coper said the best thing individuals can do is "engage parts of our brain that aren’t normally in gear when we’re scrolling through social media".

"Everyone is susceptible to misinformation. We are susceptible when we have one mode of thinking engaged, and not the bit when we’re putting our brain into gear," he said.

"The easiest thing to do is when you see something on social media that seems novel, that you haven’t heard before, is to engage in a bit of deliberation. 'Who am I seeing this from? Is this a news source I’ve heard of? Have I heard this from other people?'

"When it's something you haven't heard before, that's a good flag for you to do a bit more digging and see if you can see that validated by other sources."

That might be a news source, or the AEC website. The AEC has set up a which it says lists the main pieces of disinformation it has discovered regarding the Voice referendum, and its actions taken in response.

What should I do when I spot mis- and disinformation?

When it comes to engaging with mis- and disinformation, Coper said our first instinct can be to call it out and correct what we know to be wrong. But this can have the opposite effect.

"The way social media works is sometimes you are really just giving more engagement to something that you don’t want people to see - and more people will see it as a result," he said.

"There’s no silver bullet," he said. "For the average person on Twitter … I think it’s just [about] being able to take a moment to ask the question, ‘should I reply to this? ... What end does that serve?'

"Probably 80 per cent of the time, it would be better to not do anything at all."

If a conversation is needed, Coper encouraged a one-on-one approach "to seek middle ground".

And, when you see misinformation on a particular platform, he said it is worth flagging and reporting it with the platform.

Stay informed on the 2023 Indigenous Voice to Parliament referendum from across the SBS Network, including First Nations perspectives through NITV. Visit the

To access articles, videos and podcasts in over 60 languages, or stream the latest news and analysis, docos and entertainment for free, at the .