Later this year, Australians will vote in a referendum about whether to enshrine an Indigenous Voice to Parliament in the constitution.

The Voice is a proposed independent and permanent advisory body that would advise policymakers on matters affecting the lives of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

The scope of issues on which the Voice would provide advice has been a source of conflict in recent debates.

In the lead-up to the vote, here are all your questions answered.

What is the proposed Voice to Parliament?

The would be a body advising the government on issues particularly impacting First Nations Australians. It would not have the power to veto laws.

The Voice would make representations to both the Australian parliament and executive government on matters relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. The parliament makes laws, while the executive government develops laws and policies and administers them.

Many details on how the body would function will be worked through after the referendum, but:

- Members would have fixed-term dates to "ensure accountability"

- It would be gender balanced and include youth members

- It would draw on representatives from all states and territories

- It would include representatives from specific remote communities

- We still don't know whether members would be democratically elected or appointed.

The form the Voice could eventually take remains in the hands of parliament and would be determined after a successful Yes vote.

According to the Yes side’s proposed constitutional amendment, the parliament would retain power over the "composition, functions, powers and procedures" of the Voice.

However, according to the Voice’s , members of the Voice "will be chosen by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people based on the wishes of local communities”.

The Voice would also be allocated enough funding to allow it “to research, develop and make representations” to both the parliament and government, the Voice website says.

The scope of issues on which the Voice would provide advice has been a regular source of conflict in recent debates.

Members of the No camp have frequently suggested that its remit would essentially be boundless and would include defence and monetary policy.

Yes campaigners have stressed that the Voice , such as poverty, incarceration, child removal, and poor health and educational outcomes.

Others in the 'progressive no' camp have suggested that , and instead have called for seats in parliament and a treaty.

The Voice wouldn’t be the first Indigenous advisory body set up by an Australian government.

The Hawke government established the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission (ATSIC) in 1990, but it was abolished in 2005.

At that time, the Howard government was able to do this because ATSIC wasn’t enshrined in the constitution.

What is a referendum?

A referendum is a question put to eligible Australian voters that has the power to change the constitution, the body of rules that sets out how the country is governed.

Holding a referendum is the only way for the government to amend the constitution.

What is the Voice referendum?

The Albanese Labor government has committed to enshrining an Indigenous Voice to Parliament in the Australian Constitution. To do this, it must hold a national referendum.

Australians will be asked to vote Yes or No to changing the Constitution, formally recognising Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the First Peoples of Australia and setting up a Voice to Parliament.

If a Yes vote is successful, an Indigenous Voice along the lines of that described above will be established permanently, or at least until another referendum is held.

The decision to enshrine the Voice in the constitution is based on recommendations from the Uluru Statement from the Heart, which came out of a long consultative process with Indigenous groups.

However, Prime Minister Anthony Albanese’s decision to pursue a constitutional amendment is contested by his political opponents.

Opposition leader Peter Dutton has previously suggested that his side would support a Voice legislated by parliament. However, the Liberal Party’s Coalition partners, the Nationals, have said they don’t support a Voice legislated by parliament.

Opposition leader Peter Dutton has previously suggested that his side would support a Voice legislated by parliament. Source: AAP

To win a plebiscite, such as that held to select Advance Australia Fair as the national anthem in 1977, one side must secure a majority of votes across the nation.

However, there are two thresholds for a successful referendum: a majority of votes and a majority of states.

That’s just states, not territories; votes in the Australian Capital Territory and the Northern Territory count towards the first threshold but not the second.

Like a regular election, all eligible Australians aged 18 and over . If an eligible person fails to provide a valid and sufficient reason why they didn’t vote, they may be fined.

Australia's referendum history. Source: SBS News

The Voice will be the nation’s first referendum in almost a quarter of a century and, if successful, it will be the first time Australians have voted to alter their constitution since 1977.

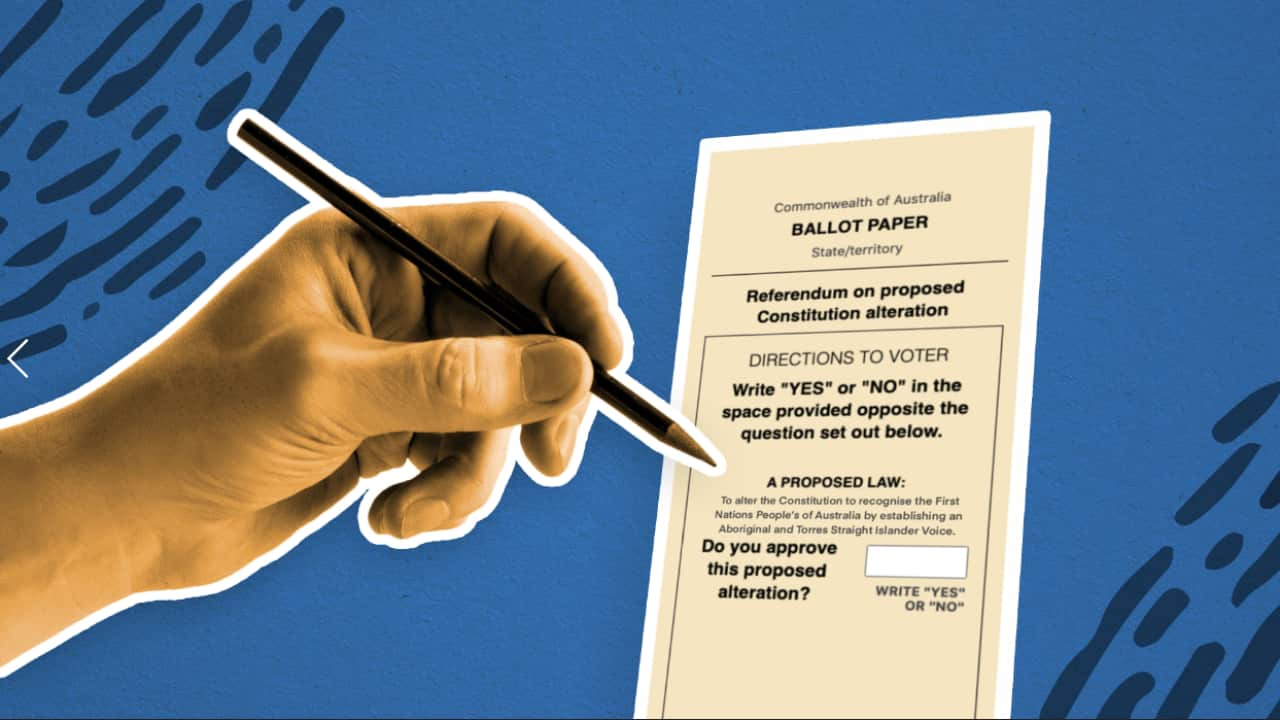

What is the Indigenous Voice to Parliament referendum question?

The question Australians will be asked to vote on in the Voice referendum was announced by Prime Minister Anthony Albanese on 23 March.

A Proposed Law: to alter the Constitution to recognise the First Peoples of Australia by establishing an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice. Do you approve this proposed alteration?

When is the Voice to Parliament referendum?

The Voice to Parliament referendum will occur on 14 October 2023.

Prime Minister Anthony Albanese announced the date of the referendum on 30 August 2023 in Western Australia. Source: AAP

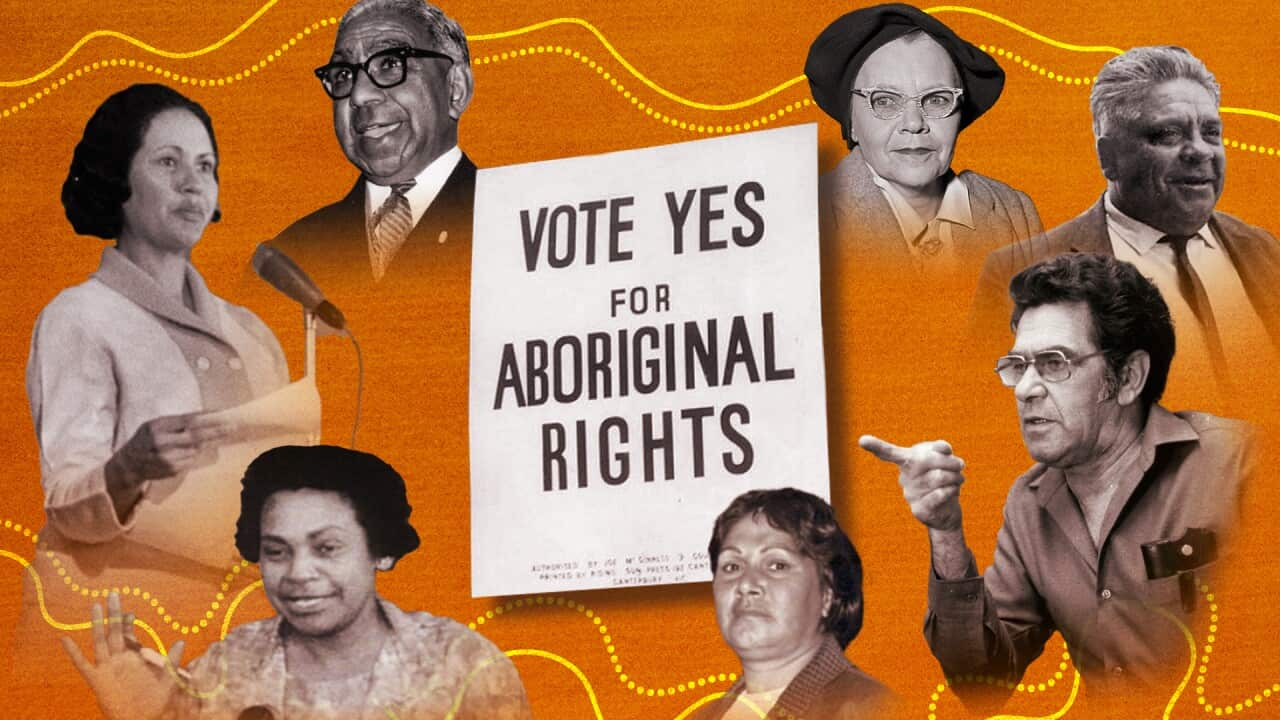

What is the 1967 referendum?

In 1967, Australia voted to remove two provisions in the Australian constitution that discriminated against Aboriginal people.

The first of these provisions related to what is known as the ‘race power’:

The Parliament shall, subject to this Constitution, have power to make laws for the peace, order, and good government of the Commonwealth with respect to:- …(xxvi) The people of any race, other than the aboriginal people in any State, for whom it is necessary to make special laws.

The proposed amendment was to remove the words “other than the aboriginal people in any State” from this section.

This gave the federal government, rather than state governments, the power to make laws for Indigenous Australians.

Before the 1967 referendum, there were state-by-state differences in the laws that applied to Indigenous people.

For example, in NSW, Victoria and SA, Indigenous people were able to marry freely and vote freely (from 1962), but those living in WA and Queensland could not.

At the time, advocates for a Yes vote sought to put pressure on the federal government to use its new power to provide positive policies for Indigenous people.

The second provision altered by the 1967 referendum related to counting Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in official population numbers.

It sought to remove the following section from the Australian constitution:

In reckoning the numbers of the people of the Commonwealth, or of a State or other part of the Commonwealth, aboriginal natives should not be counted.

The referendum was overwhelmingly won by the Yes side, with over 90 per cent of Australians in support.

As well as the legal changes it brought about, the referendum quickly took on an important symbolic value and it was followed by campaigns such as the 1972 Aboriginal Tent Embassy and the land rights movement.

Referencing the changes to Section 127, the final paragraph of the Uluru Statement from the Heart reads: “In 1967 we were counted, in 2017 we seek to be heard.”

- It gave Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people the vote

- It officially granted Indigenous people citizen rights

- It gave equal rights in Australia

None of these ideas about the 1967 referendum are strictly true.

What is the Uluru Statement from the Heart?

The is the culmination of a series of dialogues held with First Nations representatives, which arrived at a consensus about what constitutional recognition should look like.

It is that calls for the establishment of an Indigenous Voice to Parliament enshrined in the constitution and a Makarrata commission for the purpose of treaty-making and truth-telling. Makarrata is a Yolngu word that refers to coming together after a struggle.

According to the statement, Makarrata “captures our aspirations for a fair and truthful relationship with the people of Australia and a better future for our children based on justice and self-determination".

The sequence of the statement’s recommendations is also important, particularly a constitutionally enshrined Voice as the first order of business.

“We’re starting with the ‘big law’ – the Constitution is the highest law in the land. This is the best way for us to ensure tangible outcomes to improve the lives of First Nations peoples,” reads the official Uluru Statement website.

“To put it very simply, the Uluru Statement from the Heart is almost like a sales pitch to the Australian people as to why we need constitutional reform,” one of the statement's authors, Professor Megan Davis, .

The Yes camp has often highlighted the consultative nature of the document’s construction, but some prominent No campaigners have said that the statement doesn’t reflect the will of all Indigenous people.

"There are a lot more Indigenous Australians out there who don't feel like they've been represented through the Uluru Statement from the Heart," Opposition Indigenous Australians spokeswoman Jacinta Nampijinpa Price has previously said.

Source: Facebook / The Uluru Statement from the Heart

Its launch came after the 16-member Referendum Council engaged in dialogues with over 1,200 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander representatives across Australia over a six-month period.

Members of the Referendum Council include Pat Anderson, Megan Davis and Noel Pearson.

While the Uluru Statement was promptly dismissed by the Turnbull government and the Morrison Coalition government refused to support a Voice referendum, there was some progress on the design of the Voice during those years.

The Albanese Labor government was the first to fully embrace the document.

“On behalf of the Australian Labor Party, I commit to the Uluru Statement from the Heart in full,” were some of the first words Albanese said in his speech after winning the May 2022 federal election.

"[It is a] concise, uplifting Uluru Statement from the Heart. On one page, a single page, a gracious invitation to non-Indigenous Australia to advance our country," he said in August.

The document also sets out a definition of sovereignty, a concept that has been a point of contention for those in the “progressive No” camp.

SBS Radio has shared the Uluru Statement from the Heart in 20 Aboriginal languages from communities in the Northern Territory and North Western Australia, and more than 60 other languages for Australia’s culturally and linguistically diverse communities.

What are the arguments for Yes and No in the Voice referendum?

The official Yes campaign pamphlet, released through the Australian Electoral Commission (AEC) outlines several main reasons to vote for the Voice.

It makes a two-pronged argument for the value of listening to Indigenous people's advice on matters that impact them.

The first component of this is a moral argument: that Indigenous people should rightfully have a say in shaping policies that affect them.

The second is based on policy outcomes: If the government has more policy-making input from Indigenous people, this will ostensibly lead to better results in Indigenous health, education, employment, and housing.

Yes proponents also say the Voice would be a necessary mechanism through which to negotiate Truth and Treaty processes involving the federal government. Truth and Treaty are the subsequent steps for national reconciliation outlined in the Uluru Statement from the Heart.

The Yes camp says that entrenching the Voice in the constitution means that future governments won't be able to remove it, which they see as a positive.

On the other hand, the No camp sees the idea of constitutional change as a negative.

“Putting a Voice in the Constitution means it’s permanent. We will be stuck with negative consequences,” the official No pamphlet reads.

The No pamphlet also says a Yes vote would be risky because "no issue is beyond its reach", including “the economy, national security, infrastructure, health, education and more”.

The No camp also argues that a constitutionally enshrined body “for only one group of Australians means permanently dividing Australians".

“This goes against a key principle of our democratic system, that all Australians are equal before the law,” the No pamphlet reads.

The No pamphlet also says that Australians are being “asked to sign a blank cheque” as details about the Voice “would only be worked through after Australians have voted".

Senator Jacinta Nampijinpa Price, the Opposition's Indigenous Australians spokeswoman and prominent No campaigner has previously said: "Australians deserve details, consultation and transparency. Instead, we’ve been given a proposal that is risky, full of unknowns and enshrines division in the constitution."

There is also a separate No camp, sometimes called the 'progressive No'. As opposed to the 'conservative No' camp, which argues that a constitutionally enshrined Voice goes too far, the 'progressive No' say it doesn’t go far enough.

They take issue with the fact that the Voice will only have advisory powers, with the parliament and legislature maintaining ultimate decision-making authority.

They say that recognition of sovereignty and truth-telling is the key to real change.

Senator Lidia Thorpe, for example, has attacked the Voice to Parliament as

In a self-released Voice pamphlet, Thorpe say the Voice is “not a step in the right direction, but "another powerless advisory body" and that it’s a "destructive distraction" and would "absolve the government of its continued crimes".

Independent Senator Lidia Thorpe and Warlpiri elder Ned Hargraves speak during a press conference at Parliament House. Source: AAP / Lukas Coch

The embassy was set up in January 1972 when Michael Anderson, Billy Craigie, Bertie Williams and Tony Coorey marched on Canberra to protest a land rights announcement by then prime minister William McMahon.

Opposite the building now known as Old Parliament House, they planted a beach umbrella and erected a sign reading 'Aboriginal Embassy'. The embassy is an ongoing site of protest.

Embassy representative Nioka Coe, Craigie's daughter, has said people at the encampment had not been consulted about the Voice. In August, Coe called the proposed constitutional change a "tokenistic gesture".

"I don't think we need to be added to a constitution that oppresses our people," she said.

Who is involved in the YES campaign?

Perhaps the most prominent campaign in support of an Indigenous Voice to Parliament is Yes23. Led by the group Australians for Indigenous Constitutional Recognition (AICR), it calls itself a grassroots coalition that is supported by many organisations.

Yes23 is currently organising and training volunteers to actively campaign in their local area, including knocking on doors, handing out flyers and making phone calls.

In parliament, the push for a Voice is , the Greens, and most independent MPs. Indigenous Australians Minister Linda Burney is also a prominent figure in the campaign.

A small number of Liberal MPs, such as Bridget Archer and Julian Leeser, . Former Liberal leaders such as Malcolm Turnbull and John Hewson have also expressed support for a Yes vote.

The premiers of all states and territories , including the Liberal premier of Tasmania Jeremy Rockliff.

Trade unions and the Business Council of Australia are making a rare show of unity in support for the Voice. Many unions are actively campaigning for a successful vote and prominent businesspeople, such as Michael Chaney and Daniel Gilbert, sit on the board of Yes23.

Notable Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander figures in the Yes campaign include Professor Megan Davis, Noel Pearson, Thomas Mayo, Tom Calma, Marcia Langton and Pat Anderson.

They’re all long-term, prominent advocates for Indigenous social and economic justice who’ve been intimately involved in shaping the Voice proposal.

Davis, Anderson and Pearson were all co-chairs of the Referendum Council, a body set up in 2015 that consulted with hundreds of Indigenous people and eventually produced the Uluru Statement from the Heart.

Calma and Langton were co-chairs of the

Mayo is a signatory to the Uluru Statement from the Heart and a director for Yes23 and AICR. He also recently co-authored a book called The Voice to Parliament Handbook.

Pearson’s think tank, the Cape York Institute, also runs a subsidiary group called From the Heart that has been playing a prominent role in pro-Voice education campaigns. He's also a director of Yes23.

Who is involved in the NO campaign?

The No campaign is being run by multiple groups with different reasons for opposing an Indigenous Voice to Parliament.

Recognise a Better Way and Fair Australia, the latter of which operates under the auspices of conservative lobby group Advance Australia, are two of the most prominent.

Earlier this year, they combined their efforts into a single campaign called Australians for Unity and, like Yes23, are mobilising people to campaign in their local areas.

Several prominent Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are leading figures in the campaign, including Senator Jacinta Nampijinpa Price and Warren Mundine.

Senator Jacinta Nampijinpa Price is among those leading the No campaign. Source: AAP / Mick Tsikas

The following year, he was appointed as chairman of the then Coalition government’s Indigenous Advisory Council by then-prime minister Tony Abbott.

Price formerly served as a councillor and deputy mayor of Alice Springs. Like Mundine, she also unsuccessfully ran for a lower house seat in the 2019 election. She was elected as an NT senator in 2022 and currently serves as the Opposition's Indigenous Australians spokeswoman.

In parliament, both the Liberal and National parties are campaigning for a No vote although, as mentioned above, several Liberal Party parliamentarians .

Opposition leader since his party announced its formal opposition to the Voice earlier this year.

The National Party announced its opposition to the Voice even earlier, and party leader David Littleproud has regularly spoken against it in parliament and to the media.

Former Liberal Party prime ministers John Howard and Tony Abbott have also publicly criticised the Voice proposal, although the latter has been far more present in the No campaign.

One Nation leader Pauline Hanson has also long been an outspoken opponent of the Voice.

Some are also campaigning from a "progressive No" perspective. Former Greens - now independent - senator .

Thorpe has consistently demanded Truth and Treaty instead of what she calls the "powerless" Voice.

In , Thorpe said the government should call off the referendum, but also suggested there was still time for Labor to convince her to back the Voice.

Independent Senator Lidia Thorpe at the National Press Club in Canberra. Source: AAP / Mick Tsikas

What are the YES and NO pamphlets?

Australian law requires the AEC to send out official information to households at least two weeks before a referendum.

Both Yes and No camps in the Voice to Parliament referendum signed off on their official pamphlets in mid-July and they’re already available via the .

In terms of the print versions, AEC spokesperson Pat Callanan told ABC Radio Melbourne in mid-August that the organisation was “hoping to start getting those pamphlets out to mailboxes by mid to late August and then it should be out to all of Australia by the end of September hopefully".

Neither the Yes or No pamphlets are fact-checked, even for typos, and are published exactly as submitted to the AEC.

However, SBS News has worked with the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology's FactLab CrossCheck team .

The official Yes and No pamphlets for the Voice referendum will soon be landing in mailboxes. Source: SBS News

The pamphlets are written by majority groupings of politicians who support either side, although the legislation doesn’t clearly spell out how this process should operate.

Each side gets 2,000 words to make its case.

Labor, the Greens, pro-Voice Liberal MPs, and a host of independents were consulted on the Yes pamphlet's contents.

The No campaign’s pamphlet was mainly written by Coalition politicians. “Progressive No” advocates such as Lidia Thorpe, who , were not consulted.

Under the banner of the Blak Sovereign Movement, the “progressive No” camp has released pamphlet.

How can you access referendum information in languages other than English?

The AEC has to help people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds understand the referendum process.

The official referendum booklet - including pamphlets outlining the arguments for and against a Voice to Parliament – has been translated into over 30 international languages. Information is also available in 13 First Nations languages.

What kind of misinformation has spread about the proposed Voice?

Misinformation about what the proposed Voice could mean for Australia if it passes has been circulating online in the lead-up to the referendum.

One of the most prominent claims that has been spread about the Voice is that it would divide Australia by race, or give special rights to one race of people.

The proposed law Australians are being asked to approve would insert lines into the constitution recognising Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the First Peoples of Australia.

RMIT CrossCheck told SBS News the Voice "does not propose any racial segregation policies".

It would be "an advisory body that makes non-binding representations to parliament, and which may recommend changes to improve laws and policies that have an impact on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples".

Constitutional law expert Cheryl Saunders said in her view, this does not mean Australia will be divided by race, or that Indigenous people will have special rights.

"We're recognising Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people because they were the first peoples here, not on the grounds of race," she said.

Race is already mentioned in the constitution. Section 51(xxvi) allows parliament to make special laws for people of "any race for whom it is deemed necessary to make special laws".

Another prominent piece of misinformation that has emerged is that the Voice will lead to policies that favour Indigenous people, such as land tax, property rights, and non-Indigenous people losing their properties or having to pay rent.

According to RMIT CrossCheck, the Voice is not designed to enable any such policies: the constitutional change would not convert private land to native title, and the Voice would have no formal power to force policy changes or control Australia’s land and resources.

There have even been claims the United Nations will control all land in Australia if the referendum is successful.

RMIT CrossCheck investigated suggestions of the UN using the voice to upend sovereignty and found the claims were incorrect.

Australia is a voluntary member state of the intergovernmental organisation, and the UN is not authorised to intervene in matters that fall under the domestic jurisdictions of its members.

What will happen if the Voice referendum fails?

If a No vote is successful, an Indigenous Voice will not be enshrined, and the constitution will remain unchanged.

It’s unlikely another referendum will be held on the question in the short-term. Albanese framed the referendum as a in April.

“If this isn't successful, it's not like a month later there'll be another referendum around," he said.

In August, Albanese suggested an alternative form of recognition would not be implemented if the Voice referendum is not successful.

The Voice is one of three aspects of the Uluru Statement from the Heart – alongside Truth and Treaty – that Albanese’s government committed to after winning the 2022 federal election.

A No vote in the Voice referendum wouldn’t automatically impede the government from following through on its commitment to processes like establishing a treaty.

But some advocates for the Voice have suggested that its establishment is .

“I just don't know how we will be able to do that when we are still voiceless in the community,” Sally Scales, a member of the Voice referendum group, told SBS News in May.

“How would we be able to do a Treaty process if we don't have a voice to have that negotiation with government?"

Are there versions of a Voice to Parliament elsewhere in the world?

Norway, Finland and Sweden designed to ensure Indigenous perspectives are presented to their governments for consideration on issues affecting these communities.

The Sámi people are indigenous to an area that covers parts of the three countries. Sámi Parliaments were established in Norway in 1989, Sweden in 1993 and Finland in 1996.

All three national bodies make representations to the respective national governments on matters impacting Sámi people.

The bodies' representations help inform legislation to best reflect the interests of the Sámi people on relevant issues. Representatives are elected every four years.

Sámi parliaments are not entrenched in their countries' constitutions. Instead, their existence is legislated.

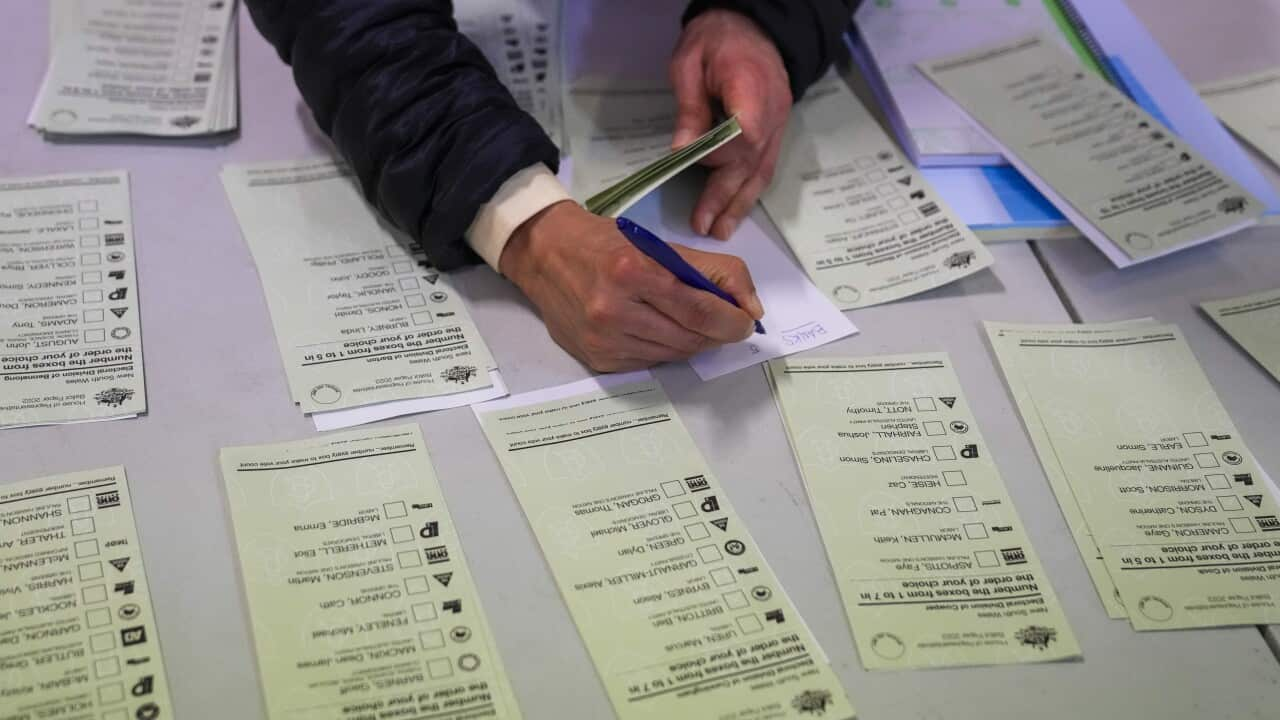

How do you cast your vote in a referendum?

Unlike federal elections, where you choose parties and candidates by filling in numbers on ballot papers, the referendum paper will ask you to answer the question on it by writing one word: "Yes" or "No".

The process is being overseen by the AEC, and, as with other elections, there will be a number of ways you can cast your vote.

In-person voting

If you're on the electoral roll, you can go to a polling place to cast your vote. Just like the federal election, there will be thousands across the country in places such as schools, community centres, church halls and surf lifesaving clubs.

The AEC says you can cast your referendum vote at any polling place in your state or territory. Polling places will be open from 10am to 6pm on the day. The AEC will list polling places on its website.

Once you’re there, your name will be marked off the electoral roll and you'll be given the ballot paper. Take it to one of the cardboard booths in the polling place, write Yes or No on the paper and then put it in the ballot box.

Postal voting

If you can’t make it to a polling place on the day of the referendum, you’re eligible to cast a postal vote - either on voting day or during the early voting period.

If you're eligible, you can apply for a postal vote Applications opened for the 2023 referendum on 11 September, after a writ was issued to the AEC by Governor-General David Hurley. Postal vote applications will be open until 6pm on 11 October.

If you're already registered as a , you'll receive your referendum ballot paper in the mail.

The Voice referendum ballot will come with clear instructions to write "Yes" or "No".

Voting in remote areas

The AEC will be servicing more remote areas in this referendum than in any other vote held in Australia.

Teams will visit remote areas in the three weeks before referendum voting day to collect votes.

Telephone voting

This option is only available for people who are blind or have low vision, or who are working in Antarctica.

You'll need to contact the AEC to register and confirm you are eligible to vote in the referendum by phone. Once you have registered, you'll receive a separate phone number to call and cast your vote.

Registration for telephone voting will be available after the issue of a writ in the referendum, and will be provided .

Residential care, homeless shelters and prisons

The AEC will send mobile polling teams to many residential aged care facilities, residential mental health facilities, homeless shelters and prisons.

Can I wear whatever I like to a polling booth?

Beyond the normal standards of decency, there are some specific rules about clothes you can wear while voting in a referendum or election.

Wearing a pin, shirt or hat with a campaign slogan into a polling may not necessarily count as a campaigning. However, seeing as campaigning inside polling venues is against the rules, a problem could arise if a voter is seen talking about the campaign-related apparel.

The AEC advises voters that it's easiest to simply avoid any potential issue by not wearing campaign material into a polling place — "or to at least bring along a piece of clothing that allows a voter to cover up".

How can you vote early in the referendum?

Early voting centres opened in Victoria, Western Australia, the Northern Territory and Tasmania on Monday, 2 October.

In NSW, Queensland, South Australia, and the ACT, they opened on Tuesday, 3 October.

Is it compulsory to vote in the Voice referendum?

In a word, yes.

Electoral Commissioner Tom Rogers said all eligible Australian citizens aged 18 years and over are required by law to enrol and vote in the referendum.

Rogers said people should check if their enrolment is up to date. "...the instruction is simple - if Australians are unsure of the status of their enrolment, they should jump on now and make sure their details are up to date.”

If you do not vote, which is illegal, you will receive a failure to vote notice from the AEC, be forced to explain why you did not vote and may be fined.

People who are – the day of the referendum – are eligible to vote.

If you've been notified of your citizenship ceremony date, and it's scheduled for referendum day or earlier, you must complete the provisional enrolment form available on the AEC website.

How will overseas voting work for the referendum?

If you’re overseas during the referendum voting period, you can vote by postal vote or in person at an overseas voting centre. There will be voting centres at embassies, High Commissions and other Australian diplomatic outposts overseas.

Australians voting overseas will see in-person voting services returning to pre-pandemic levels. There'll be around 100 in-person overseas voting centres available, with fast-tracking arrangements as there were during the 2022 federal election.

If you vote by post, it has to be received by the postal voting deadline, which is 13 days after the referendum date.

The AEC says you don’t have to vote in the referendum if you are overseas, but you should tell the AEC.

If you don’t, it will write to you at your address in Australia asking why you didn’t vote. If you’re working in Antarctica, referendum rules mean you can vote by telephone.

Can you still enrol to vote in the referendum?

Enrolment for the Voice to Parliament referendum closed at 8pm (AEST) on Monday 18 September.

If you haven't enrolled yet, you are unable to participate in the referendum.

However, you will already be on the electoral roll if you have previously voted in a federal election.

How do you check your enrolment or update your enrolment?

To maintain your privacy, your enrolment will only be confirmed if the details you enter exactly match those on the electoral roll.

If you can't confirm your enrolment this way, but believe you are enrolled, you can and find another way to check your enrolment details.

You can update your details, such as your address, through of the AEC website. However, you can only update to a new address if you've been living there for at least a month.

The AEC webpage linked above contains instructions to update other details, such as your name.

Updating your details will also require identification documents, similar to those required for enrolment, such as a driver's licence, Australian passport number, Medicare card number or an Australian citizenship number.

You can also fill in physical forms which are available online or from an AEC office, and return them to the AEC office.

The AEC may have updated your details if they have obtained your details from another government agency, which the law allows them to do.

What are some common disinformation claims about the referendum?

As the referendum draws closer, the campaign has become shrouded by . As such, voters face the increasingly urgent challenge of separating fact from fiction.

The Australian Electoral Commission (AEC) – the independent federal agency in charge of organising, conducting and supervising the referendum – has launched a specific to the referendum, to track and counter misleading claims.

One common disinformation claim about the referendum is that the AEC is compromised by corruption, mismanagement and bias, and the referendum will be 'rigged' as a result.

The AEC has directly responded to these claims online, reminding people it is “the neutral body administering elections to world leading integrity standards”, and doesn’t “advocate how people should vote, just that they do vote”.

The AEC explains on its website that the Voice referendum will be run using the same infrastructure as federal elections, which includes more than 100,000 temporary staff counting the votes under the supervision of both AEC staff and independent scrutineers. Independent experts have also told SBS News that the AEC has a respectable track record.

Another claim about the referendum is that, by accepting a tick on the ballot paper as a formal Yes vote, but not accepting a cross as a formal No vote, the AEC is favouring a Yes vote.

It’s worth pointing out this isn’t a new rule – the AEC says it has followed legal advice about ticks and crosses on referendum ballot papers for more than 30 years.

Parliament is ultimately responsible for setting how ticks and crosses are interpreted, and the AEC has "made no decision" on the matter, AEC commissioner Tom Rogers has told SBS News.

A federal court ruling on 20 September 2023 affirmed this decision, saying it has been legal precedent across six referendums.

Federal court judge Steven Rares said that a cross could indicate agreement, disapproval or an unwillingness to answer the question at all, while a tick was not similarly ambiguous, either indicating approval or an affirmative response.

Furthermore, the overwhelming majority of voters follow the instructions to write Yes or No on the ballot paper. In Australia’s last referendum, the rate of informal votes (which aren’t counted) was 0.86 per cent. The AEC says even among those, “many would have no relevance to the use of ticks or crosses”.

The AEC has repeatedly urged Australians to write either "Yes" or "No" in English, in full, on their ballot papers to ensure their vote would count.

When will we know the results of the referendum?

The counting process for the referendum will be similar to that employed for votes for the House of Representatives in a federal election, with the key difference being people are only answering Yes or No on one ballot paper in the referendum.

The streamlined counting process (federal election vote counting needs to take preferences into account) means it’s likely we’ll know the result on the night.

However, the AEC uses the slogan ‘right, not rushed’ on its website and says if the overall result is close, it may require up to 13 days after polling night for the result to be known. This is the time frame the AEC allows for postal votes to come in.

As for the mechanics of the vote count, the AEC says every vote cast on the day of the referendum will be counted that night.

Most of the votes counted at early voting centres and a small number of postal votes will be counted as well.

Results will be uploaded to the AEC's Virtual Tally Room as they're counted, both on the day of the referendum and the days following.

The AEC says it will only declare the referendum result when it’s “mathematically impossible for any other result to occur".

What happened at the last referendum?

The last time a referendum was held . It had two questions, and both failed to get anywhere near enough Yes votes to pass.

Australians were asked to vote Yes or No on altering the Constitution to establish a republic - replacing the Queen and governor-general with a president - as well as altering the Constitution to add a preamble..

The push for Australia becoming a republic was led by Malcolm Turnbull, with former prime ministers Gough Wihtlam, Bob Hawke and Malcolm Fraser also arguing Australia's head of state should be an Australian. The official No campaign argued that the system proposed would create a "politician's republic" and was undemocratic.

There was no majority for Yes in any state. Overall, 54.9 per cent voted No to the republic, and 60.7 per cent to the preamble.

After successive Labor and Liberal prime ministers have said they wouldn't revive the republic debate, there was speculation Anthony Albanese would push for an Australian head of state once he became prime minister.

The Republic Movement has said it has paused much of its campaigning until after the Voice referendum.

I've received a text message about postal voting. What should I do?

Some Australians have recently reported receiving a text message urging them to vote No, and also to apply to make a postal vote.

The text message includes a link to a website authorised by the Liberal Party. The website lists some of the reasons a person may seek to vote via post and has an 'apply' button beneath them.

Upon clicking on it, people are asked to provide details including their name, address, email address and phone number.

When being asked for the last of these details, people are informed by submitting one's details "you will be providing this information to the Liberal Party of Australia and the Nationals, who will contact you regarding the referendum". Upon giving that information, the page redirects to the AEC's postal vote application.

The Australian Communications and Media Authority (ACMA) has confirmed to SBS News that messages from registered political parties do not have to comply with the Spam Act.

ACMA advised complaints relating to such messages should be directed to the authoriser.

Political parties sending physical postal vote applications to people who request them or providing a link to the AEC's online application form is not illegal.

However, Electoral Commissioner Tom Rogers last year described the practice as "potentially misleading" and the "number one complaint" received in regard to the federal election.

The AEC refers to it as sending "third-party postal vote applications".

The Liberals are not the only party who have used websites to get voters to register for postal votes through them. For last year's federal election, Labor set up the website howtovote.org.au for that purpose. The website is no longer active.

"This is an application with no ballot papers involved," Australian Electoral Commission spokesperson Evan Ekin-Smyth said.

"If a political party receives a postal vote application, they're obligated to send it swiftly back to the AEC. We then process everything.

"The AEC handles your ballot papers for postal votes.

"Ballot papers are sent from the AEC directly to a postal voter, it comes directly back to the AEC."

Applying for a postal vote directly through the AEC’s website removes the unnecessary middleman, so people who request a physical ballot paper in the mail would likely receive it quicker.

Your information will also be afforded a level of protection.

"If you're at all concerned about your privacy because there is personal details involved in applying for a postal vote, the AEC has to operate under the Privacy Act, political parties do not, so our advice, once again, is to come to the AEC directly," Ekin-Smyth said.

Why aren't territory votes equal to state votes?

In the upcoming Indigenous Voice to Parliament referendum, votes in the ACT and Northern Territory only count for one-half of the double-majority required for successful constitutional change.

Votes in the territories will count for the purposes of calculating the national majority, but not for the majority of states.

This difference in status is arousing controversy, given the topic of this referendum and the fact that the Northern Territory is home to the highest proportion of First Nations people of any jurisdiction – roughly 30.8 per cent.

This variation in voting power is because the states and territories have different constitutional status. The constitution recognises the the states as independent, sovereign entities, with guaranteed powers of self-government.

The territories, on the other hand, are ultimately controlled by the Commonwealth, which can pass laws for them and even override laws passed in territory parliaments.

In fact, between 1911 and 1977 people living in territories couldn't even vote in referendums.

Between 1901 - the year of federation - and 1911, the Northern Territory and ACT were part of South Australia and NSW, respectively. As such, their residents had the same voting rights as those of any state.

However, when the Northern Territory and ACT became federal territories in 1911, their residents lost those rights.

It wasn't until a successful referendum in 1977 that they won them back, via an amendment that required referendum questions to be put to electors "in each State and Territory".

However, that amendment didn't alter the requirement for a majority of states to vote Yes for a successful referendum.

How to spot misinformation and what to do about it?

Experts are warning of an "incredibly large volume" of mis- and disinformation that is circulating in the referendum campaign.

Mathew Marques, a senior lecturer of social psychology at Melbourne's La Trobe University, said there are two key questions to ask yourself - what is the source, and how is the content being communicated to you?

"If you’re able, I would start off by checking the source of the information. For you, is it a trustworthy source? Is it likely to be an impartial source?"

Then, check whether the content has any "hallmarks of persuasive language" that might "draw you in".

When you see misinformation on a particular platform, it is worth flagging and reporting it with the platform.

This article was originally published on 29 August. It is being regularly updated.