Key Points

- Barnaby Joyce raised his issues with the proposed Voice to Parliament while appearing on NITV's The Point.

- Nova Peris, Karen Mundine and Kate Carnell also appeared on the panel, refuting many of Joyce's statements.

- Peris described the Constitution as a birth certificate for the country where the "first-born" had been left off.

Nationals MP Barnaby Joyce railed against the proposed Indigenous Voice to Parliament when appearing on NITV's The Point program on Tuesday night.

He was one of four panellists who spoke on NITV’s Indigenous current affairs program as it examined issues surrounding the upcoming Voice referendum. You can watch the episode on

Joyce sat on a panel with former senator and Olympian Nova Peris from the Australian Republic Movement, Karen Mundine from Reconciliation Australia, and head of Liberals for Yes, Kate Carnell.

While on the program, Joyce said he believed a Voice would give some people a “greater parliamentary right”, questioned what the legislation might look like and expressed concern that a Voice would “cause more problems”.

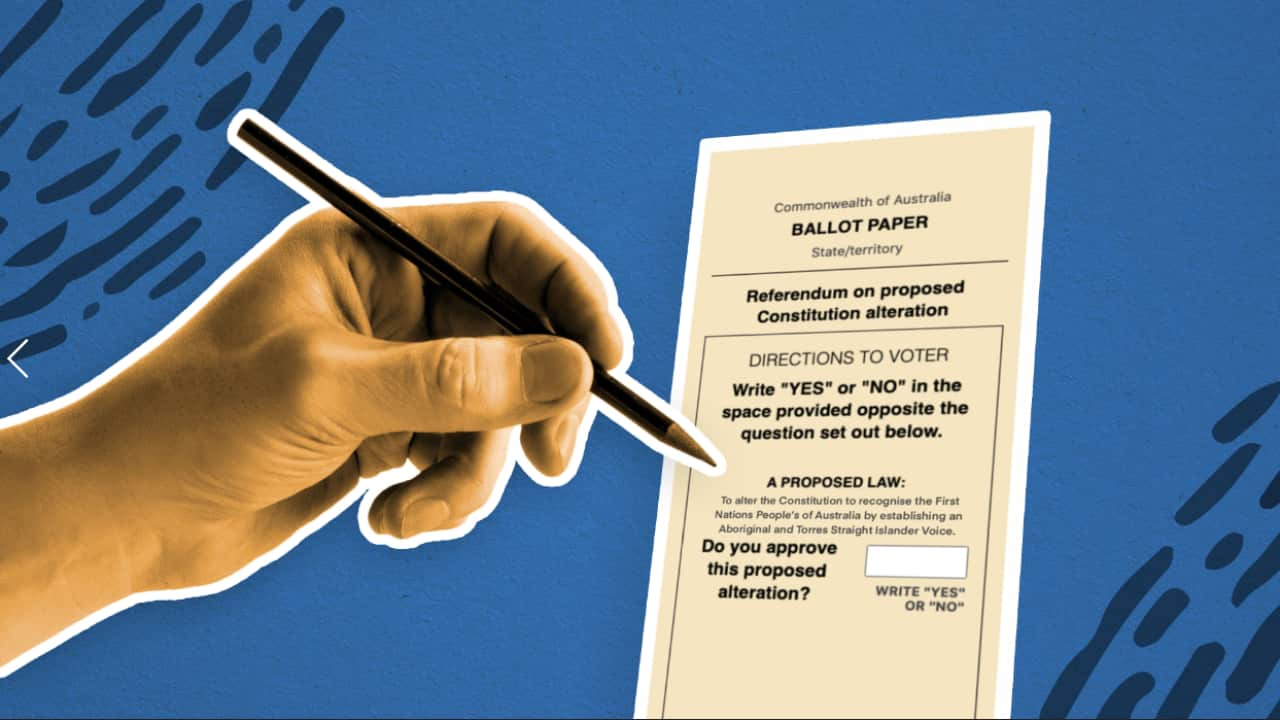

Australians will about whether to enshrine an Indigenous Voice to Parliament in the constitution.

The Voice is a proposed independent and permanent advisory body that would advise policymakers on matters affecting the lives of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

'A greater parliamentary right'

Joyce said one of things that “annoys” him about the idea of an Indigenous Voice to Parliament was that based on race, some Australians would have greater rights and that the Constitution would separate people by race.

“So two people born in the same hospital, in beds next to each other, go to the same primary school, go to the same high school and live next to each other in the same village and one gets a greater parliamentary right than the other person. People have to see how that annoys me,” he told the program.

Joyce said he’d grown up being told not to define people by race but in the case of the Voice, it's a case of “Well, hang on, except on certain occasions, where we will define people by race".

Peris disagreed with Joyce, pointing out how the Constitution from the outset defined people by race to the detriment of Aboriginal people.

Nova Peris. Credit: NITV

“Fast forward, 1901. This document. 1901 is the birth certificate of this country. Now, there were two references to Aboriginal people in there in 1901: that the Commonwealth shall make law for whom it deems necessary for except the Aboriginal race … and the other one was the Aborigines could not be counted, so we weren't allowed to be counted as part of Australian population,” she said.

“We have been subjected since day dot in this country to brutal acts that have hurt our people," Peris added. "It's a very simple thing what we're asking ... The birth certificate of this country does not include the first-born."

The Voice legislation

“We don't know what the ledge (legislation) is, and people say it's advice and there's a lot more than that, the word advice is not even in the constitutional question," Joyce said.

“It's a capacity for people to have representations and I tell you what, if I got the High Court I want legal representation, not legal advice.”

Joyce suggested the legislation may have already been drafted. “But they just don't want to show us that yet,” he said.

Carnell refuted Joyce’s suggestion that details of the related legislation that would follow a successful Yes vote needed to be put on the public record ahead of the country voting.

“In the Constitution, there's no detail about anything. It says the federal government will run Defence. It doesn't say how, it doesn't say what the legislation might look like.

“The fact is our Constitution sets in place things like, 'We will recognise Indigenous Australians as Australia’s First People through a voice to Parliament'. It doesn't then have a copy of the legislation as it might be.”

Carnell pointed out that, following a successful Yes vote, the federal parliament would then put together the legislation determining what the Voice to Parliament would look like.

Constitutional law expert Anne Twomey previously told the ABC it would be inappropriate for the government to release draft legislation ahead of the vote.

She said the question should focus on the changes to the wording of the Constitution and it was up to the parliament to act on that.

Debate has "inflamed" people saying things "completely out of order"

Joyce said at one point on the program that the Voice debate had "inflamed people getting away with saying things that are completely out of order".

"I think it's incumbent on all of us when you hear that to say, 'No, mate, what you just said was outrageous.'"

Host Narelda Jacobs pointed out that Joyce himself had been at events with No campaigners and others who about the Voice and First Nations peoples, without explicitly disavowing them.

Later in the discussion, Mundine said it was "important" not to blame the campaign or discussion around it for the "vitriol and hatred" that had been unleashed.

"I think it's behoven on all of us, all leaders to, I guess, call it out. It doesn't matter where you sit on the spectrum. Doesn't matter whether you sit on the Yes or the No campaign. I think it's really important for this ugly behaviour to be called out for what it is and to say that it's not okay."

Karen Mundine. Credit: NITV

Constitutional recognition

Joyce reiterated that he supported constitutional recognition of Indigenous people but not a Voice to Parliament, and told the panel the “nuts and bolts” of having a body such as a Voice would cause “problems.”

Despite , Joyce still has concerns about possible challenges in the High Court, saying there could be "rogue interpretations of the Voice".

“We wanted a referendum to get through, this isn’t the one,” he said.

On Sunday, Opposition leader Peter Dutton committed to should the upcoming vote fail and the Coalition is returned to power. That referendum would focus solely on constitutional recognition, and not enshrining a Voice to Parliament - an essential part of the Uluru Statement from the Heart's calls in 2017.

"This is bringing to a head a whole range of fighting for rights, for recognition. For putting something practical behind that recognition, and also ensuring, I guess, that we have a way forward," Mundine said while appearing on the Point.

"This is a referendum which is a principle, and it's a principle of recognising Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the first Australians through a Voice to Parliament," she said.

"It was a simple proposition and it's been put from the Uluru Statement, an invitation for all Australians to walk with us."

The , the culmination of a series of dialogues held with First Nations representatives, which arrived at a consensus about what constitutional recognition should look like.

The Uluru Statement was released by a group of over 250 delegates near Uluru in Central Australia. Its launch came after the 16-member Referendum Council engaged in dialogues with over 1,200 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander representatives across Australia over a six-month period.

One of its recommendations is the enshrinement of a Voice to the Australian parliament in the constitution. The Uluru Statement marked the first formal call by Indigenous leaders for an Indigenous Voice to Parliament.

Stay informed on the 2023 Indigenous Voice to Parliament referendum from across the SBS Network, including First Nations perspectives through NITV.

Visit the to access articles, videos and podcasts in over 60 languages, or stream the latest news and analysis, docos and entertainment for free, at the .