Key Points

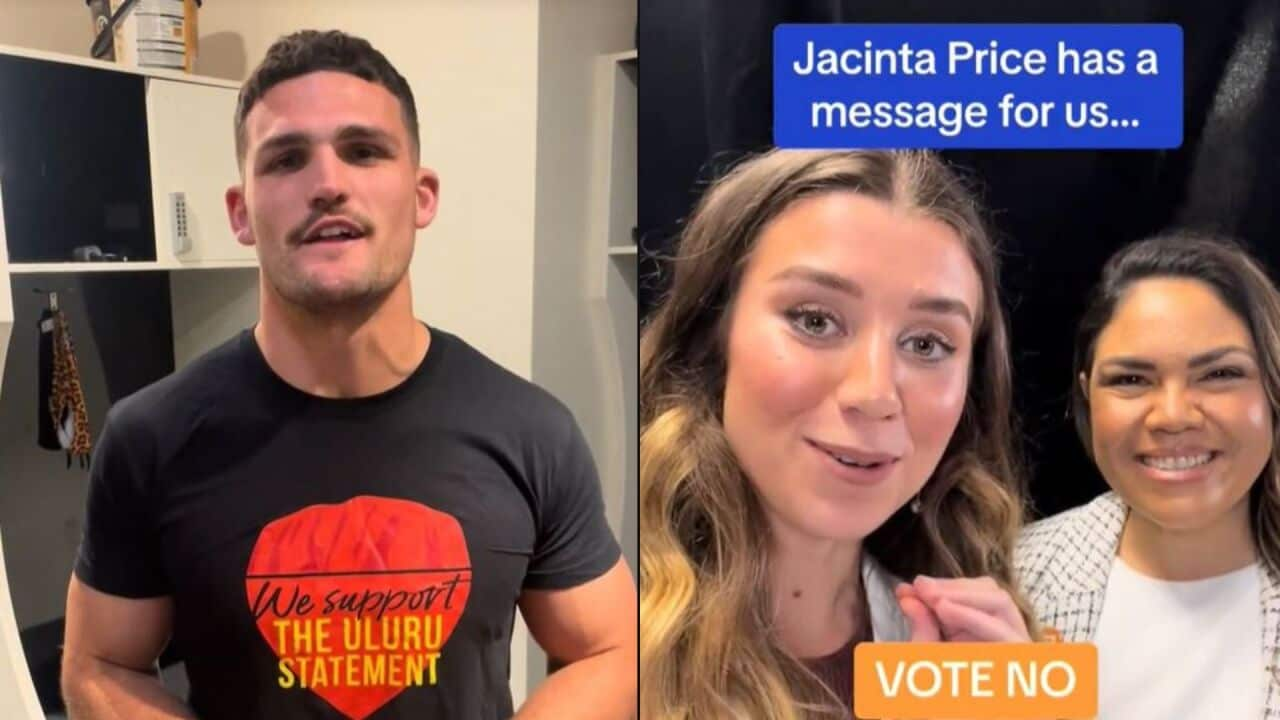

- A video of NRL player Nathan Cleary supporting the Yes campaign for the Voice to Parliament has gone viral.

- As the referendum draws closer, both sides are ramping up their campaigning on social media, particularly TikTok.

- The No movement has more followers and more views, but experts say this does not necessarily mean it's winning.

Nathan Cleary is one of the most recognisable faces in Australian rugby league, and on Monday, he also became a public supporter of the Yes campaign for an Indigenous Voice to Parliament.

On Sunday, Cleary made history by leading the Penrith Panthers to a third consecutive NRL premiership and took home his second Clive Churchill medal as the player of the match.

The next day, a short video of Cleary wearing a T-shirt supporting the Uluru Statement from the Heart was shared on TikTok.

"No voice, no choice," he said in the clip.

"Come on Australia, vote Yes."

The video was posted by Roy Ah See, a descendent of the Wiradjuri Nation and former government adviser, and shared by Prime Minister Anthony Albanese.

As the Voice to Parliament referendum draws closer, the Yes and No camps are ramping up their campaigns, with advocates from both sides taking to TikTok to argue their case.

But which side is winning, what are the laws around online political content, and can you believe what you see on social media?

How could TikTok impact the Voice referendum?

Content about the Voice referendum is prolific on TikTok, with videos being posted by news sites, politicians, campaigners, professional content creators, and everyday Australians.

The official Yes and No camps are also using TikTok to appeal to voters.

Clare Southerton, lecturer in digital technology and pedagogy at La Trobe University, said TikTok's young user demographic makes it a powerful campaign tool.

"Increasingly, other platforms like Facebook, X, or even Instagram, are increasingly struggling to hold that very young market share, and TikTok is doing that incredibly successfully," she said.

"Young people are very influential culturally, and I think that is a really big reason why they are important to target when it comes to these kinds of conversations.

"TikTok is a really important social media platform in political conversations as well because it starts media conversations."

Which side is 'winning' on TikTok?

It's difficult to measure which side is 'winning' on social media as there is limited data publicly available.

Fair Australia, a prominent No movement and led by Senator Jacinta Nampijinpa Price, started using TikTok in May and has amassed over 63,000 followers and 75,400 likes at the time of writing.

Yes campaign group Yes23 has a lower follower count at 5,120 at the time of writing, and 75,600 likes.

Numbers of views, shares, and even likes do not necessarily reflect how voters will behave at the polls, or whether those engaging with the content will actually vote.

Andrew Hughes is a lecturer in marketing at the Australian National University with a specialty in political communications and advertising.

He said while the No campaign has more followers and more videos, he believes the Yes campaign is generating more positive engagement.

"They're getting a lot more shareability of their content by far compared to No," he said.

"It could be because of the perception of those messages, or the content creators of those messages, and it's widespread amongst different age groups.

"No seem to be making a lot more content, but (with) less effect."

Southerton said it's difficult to establish whether either side is appealing to new voters as each TikTok user's feed is curated by an algorithm.

"Because it is algorithmically curated, you see what fits with what you are most likely to want to see," she said.

"It is really difficult to get a sense of who is winning when we only get to see kind of what we already believe."

Is it legal to lie about the Voice referendum on social media?

What about claims made in various official and non-official videos related to the referendum? Do they always need to tell the truth?

There are no laws that prevent lies or deceptive information in federal political campaigns in Australia.

Luke Beck, professor of constitutional law at Monash University, said the laws that apply to commercial advertising do not apply to political advertising.

"During this referendum campaign, just like during federal election campaigns, it is perfectly legal for campaigners and other people to tell outright lies.

"The reason for that is because there is no law that prevents that."

Beck said the only limitation is against misleading people about how to fill in a ballot paper.

"You can lie about a party, policies, history or whatever you want, provided that you don't go into defamation," he said.

"But is perfectly legal to make things up, to lie, or deliberately try and trick people."

Hughes describes politics on TikTok as a "free for all", particularly unpaid content posted by unofficial channels.

"If you're making your own content ... it becomes the Wild West," he said.

"You can say, 'Look, this is just me expressing my freedom of speech when it comes to an issue. It's not an ad at all. It's me having my say and having a voice on the issue.'

"And that's the power of it in some ways; so that then becomes very hard to regulate and very hard to police."

Stay informed on the 2023 Indigenous Voice to Parliament referendum from across the SBS Network, including First Nations perspectives through NITV.

Visit the to access articles, videos and podcasts in over 60 languages, or stream the latest news and analysis, docos and entertainment for free, at the .