Italian

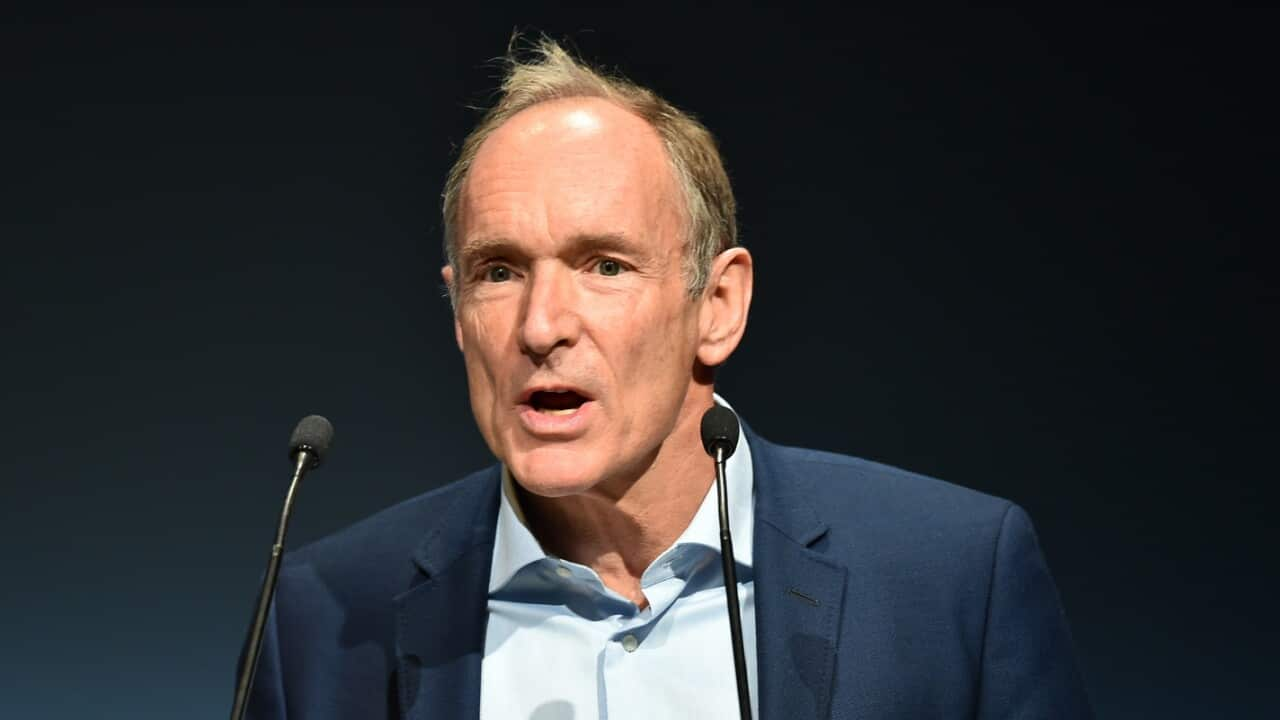

Nel 1989, un giovane Tim Berners-Lee creò il worldwide web.

Ma 30 anni più tardi, Sir Tim ammette di avere dei ripensamenti.

"It seemed like a good idea at the time, but now I think they should turn it off."

È così preoccupato che ha elaborato quello che ha chiamato un "contratto per il web".

È composto di nove principi e 72 clausole redatte per affrontare temi come disinformazione e censura, problemi che Sir Tim ritiene si siano sviluppati da quando ha dato via al web tre decadi fa.

"Ten years ago, if you just go out into the street and ask people what's wrong in the world, they'll say: 'Nothing! Everything's great!' Now, people are worried about privacy, people are worried about what happens to their data and the way it gets manipulated."

I principi sono divisi tra governi, imprese e individui.

Mentre si assicurano che tutti abbiano accesso al web, i governi dovrebbero proteggere i diritti alla riservatezza dei dati.

Le imprese dovrebbero assicurare accesso economico, sviluppando tecnologie che "incoraggino il meglio dall'umanità."

Mentre agli utenti spetta l'onere di costruire comunità online forti e rispettose.

Ma il professor Matthew Warren della Deakin University ritiene che sia troppo tardi per riparare il web.

"The web does need the guidelines, but the problem is the web is already broken and I don't think these guidelines will fix the problem. The 'contract' is a noble cause, but I believe a lost cause."

Un recente studio di Amnesty International suggerisce che la sorveglianza onnipresente di miliardi di persone da parte di Facebook e Google pone una minaccia sistemica ai diritti umani, ed ha invocato una trasformazione radicale del loro modello commerciale.

Il piano di Sir Tim è spalleggiato da due giganti della tecnologia, anche se Tim Singleton-Norton di Digital Rights Watch ritiene che il loro sostegno sia guidato dal marketing e non dalla morale.

"People are becoming a lot more savvy to what's going on here and they're actually demanding ethical product in response. To see these companies reacting to that, and actually saying 'ok well here's how we're coming to the table', that's really good."

La scorsa settimana l'handle di Twitter dell'ufficio stampa del partito conservatore del Regno Unito è stato rinominato "fact check UK", durante un dibattito tra Boris Johnson e Jeremy Corbyn - esattamente il tipo di disinformazione che Sir Tim spera di fermare.

Google ha già dichiarato che non permetterà più a inserzionisti politici di prendere di mira gli elettori.

Le prossime elezioni nel Regno Unito e negli Stati Uniti potrebbero diventare il primo banco di prova del "contratto per il web".

English

In 1989, a young Tim Berners-Lee created the worldwide web.

But 30 years later, Sir Tim says he's having second thoughts.

"It seemed like a good idea at the time, but now I think they should turn it off."

He's so concerned, he's drawn up what he's calling a "contract for the web".

It's made up of nine principles and 72 clauses designed to counteract issues including misinformation and censorship, problems which Sir Tim says have evolved since he started the web three decades ago.

"Ten years ago, if you just go out into the street and ask people what's wrong in the world, they'll say: 'Nothing! Everything's great!' Now, people are worried about privacy, people are worried about what happens to their data and the way it gets manipulated."

The principles are divided between governments, business and individuals.

While ensuring everyone can connect to the web, governments should protect rights to data privacy.

Business should ensure affordable access, developing technology "encouraging the best in humanity".

While the onus is on users to build strong, respectful online communities.

But Professor Matthew Warren, from Deakin University, believes it's too late to fix the web.

"The web does need the guidelines, but the problem is the web is already broken and I don't think these guidelines will fix the problem. The 'contract' is a noble cause, but I believe a lost cause."

A recent Amnesty International report suggested Facebook and Google's omnipresent surveillance of billions of people poses a systemic threat to human rights, and called for a radical transformation of their business model.

Sir Tim's plan is supported by the two tech giants, although Tim Singleton-Norton, from Digital Rights Watch, says that support is driven by marketing, not morals.

"People are becoming a lot more savvy to what's going on here and they're actually demanding ethical product in response. To see these companies reacting to that, and actually saying 'ok well here's how we're coming to the table', that's really good."

Last week, the UK Conservative Party's press office twitter handle was renamed "fact check UK", during a debate between Boris Johnson and Jeremy Corbyn - exactly the sort of misinformation Sir Tim is hoping to stop.

Google has already said it will no longer allow political advertisers to target voters.

Upcoming elections in Britain and the United States might become the "contract for the web's" first test.

Report by Matt Connellan