Do Arabs look down on other Arab-speaking people from different ethnic groups?

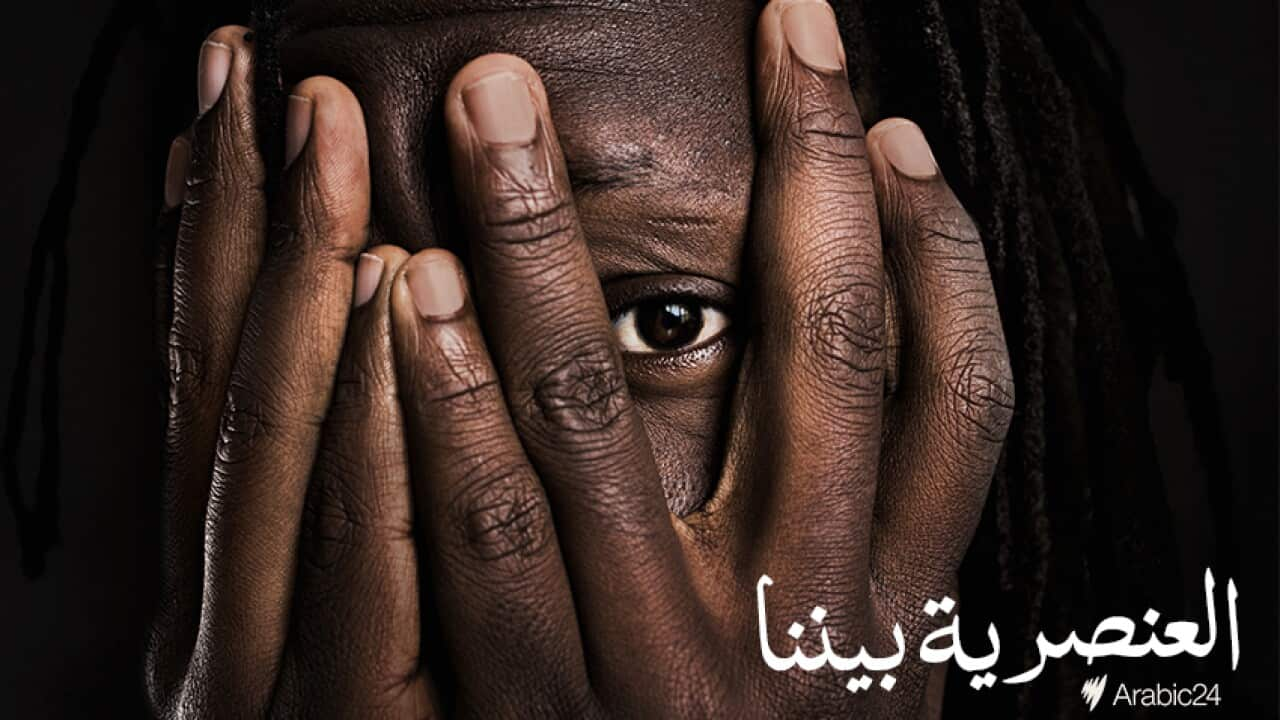

That's the question posed in the second episode of the SBS Arabic24 podcast series, ' which focuses on the lines of discrimination and persecution against minorities and vulnerable groups within Arab communities.

An Ethiopian former maid retells her "hellish" experience while living and working in Lebanon, while there are also Kurdish and Assyrian personal stories of living as second-class citizens in the Middle East.

'Hell on Earth'

Eva Agbashi left her homeland, Ethiopia, in search of a better life for her small family in Lebanon.

She worked in a house where she experienced racism and "injustices and abuse" on a daily basis.

“Thank God that I was able to leave. Before I left my country, the agent told me that I would be given a day of rest, but the reality was different," she said.

"I was getting up at six in the morning and working for fifteen hours a day."

Eva’s mistreatment was not limited to working extra long hours, but also included deprivation of the most basic of human rights.

She recalls that she fell ill one day, but the family refused to take her to the hospital for treatment.

Fortunately, she was able to reach out to the worker-rights organisation, 'This is Lebanon', which in-turn contacted the family to ensure they provided healthcare for Eva.

Farah Salka, president of the Anti-Racism Association in Lebanon, which helped Eva get through her ordeal, said Arab countries, including Lebanon, have allowed the creation of a repressive and unjust system that has put domestic workers at the mercy of "new slavery".

"The crisis we are living in is not the result of coronavirus or the economic crisis," he said.

"The problem lies in the defective sponsorship system that allows the enslavement of people. This system must be uprooted."

'Second-class citizens'

The history of Assyrians in this Middle East dates back to the Assyrian Empire, which was founded more than 5000 years ago.

Assyrians now live in northern Iraq, southern Turkey and Iran, and have roots in Syria.

Journalist Ninos Kaku from the SBS Assyrian program said since the time of the Ottoman Empire, the Assyrians have suffered persecution, and have been the victims of massacres and land grabs.

"We are viewed as second-class citizens and we have never been given the correct rights and status as the Indigenous people of Iraq," he said.

Mr Kaku explained that 70 per cent of Assyrians today do not read or write their native language because it was not included in the official education curriculum in Iraq.

His personal experiences reflect what he calls the injustices faced by many minority groups in the Middle East.

“At school and university, we were seen as outsiders because our language and looks were different."

The Kurds are among the largest stateless ethnic groups in the world, with some 30 million concentrated in an area straddling Iraq, Iran, Turkey and Syria. Kurdistan is a roughly defined geo-cultural historical region that encompasses parts of these countries.

Kurdistan is a roughly defined geo-cultural historical region that encompasses parts of these countries.

The Kurdistan flag is seen as a symbolic symbol to Kurds. Source: Getty Images

Mayada Khalil, a journalist from the SBS Kurdish program, lived and attended school in Syria as a child.

She said it left some painful memories that have never left her.

"Every time we spoke Kurdish, we had to pay 10 cents or get a slap on the hand. This was the punishment for talking in Kurdish," she said.

The void existence of stateless people of the Gulf

Asylum seeker in Australia Abu Ali* is a stateless person from Kuwait where a social problem has accumulated for decades, leaving generations without an identity.

“We are 120,000 people and part of us has been in exile. Our problems have accumulated over forty years and there is no solution looming on the horizon.”

Although the 'Bidoon' problem appeared on the surface since the founding of the Gulf states in its modern form, there doesn't seem to be a light at the end of the tunnel for those affected.

Abu Ali believes that racism played a role in depriving thousands of the right to citizenship.

“Even Kuwaitis suffer from the class system, some consider themselves more Kuwaiti than others…it is just pure racism."

The stigma associated with being stateless dominated all aspects of Abu Ali‘s life.

“The thing I really struggled with, was not finishing my education and then not getting any job.

"I was detained by police when I protested against this."

The suffering that Abu Ali endured continued when he arrived in Australia by boat in 2015.

He is seeking a visa to remain in Australia, but fears that he has become subject to the country's strict policies in dealing with arrivals by sea.

"I was a stateless person from Kuwait and I became a stateless person in Australia.”

Addressing the problem

While most religions preach equal rights for all humans, there remain some forms of racism behind closed doors in many Middle Eastern households.

Some do not see a problem if their maid works non stop from dawn to sunset, or refuse to accept a marriage proposal from their daughter's boyfriend because he is black.

Mr Kaku said a solution to this deep-seated racism and persecution may lie in education from a young age, which is currently lacking.

"Unfortunately, the curriculum in the Arab world does not have a subject about tolerance or acceptance for those who are different in religion, ethnicity, look, or history.”

Farah Salka said a solution may be to amend the laws in these countries.

“We are talking about people who came to us for a better life, to make money and go back home, yet some of them return home in coffins or be buried here.

"Domestic helpers need to be covered by laws and protected by them.”

For Ms Khalil, the answer is simple: "To live in safety and peace we need to accept each other, and for love to be our first and foremost goal.”

* Not their real name