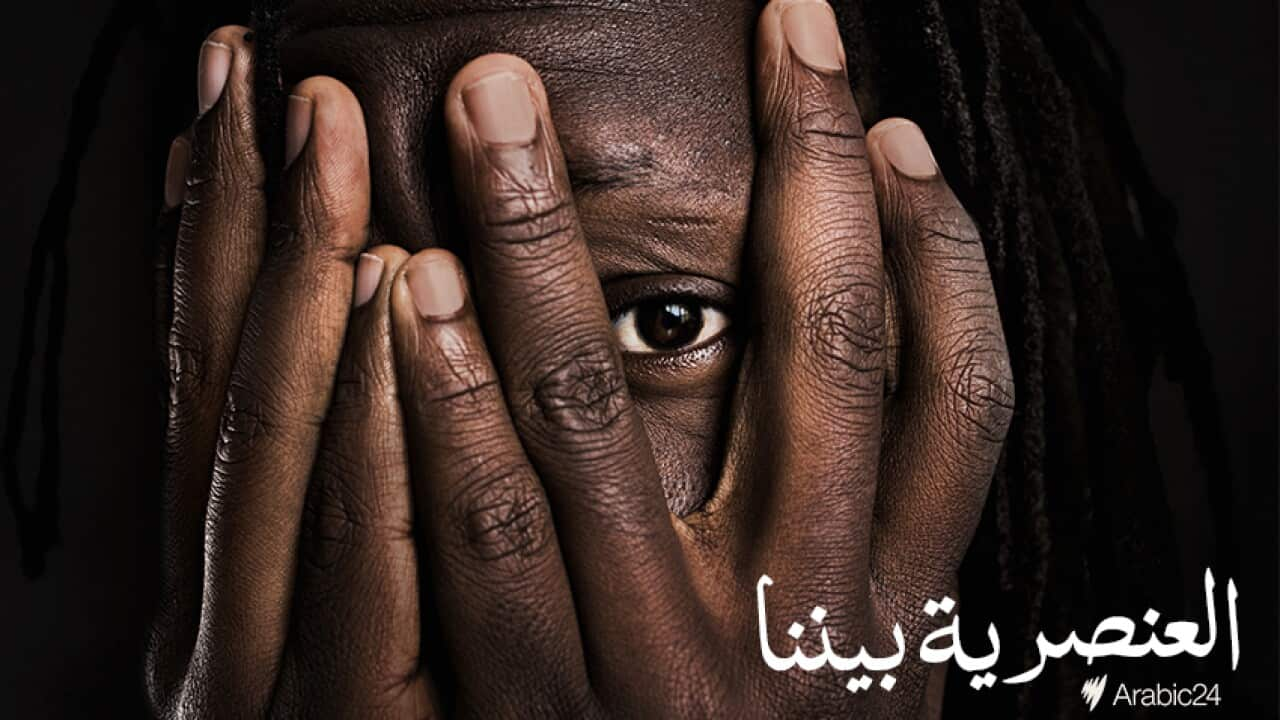

Racism. This malicious word can disguise itself and infiltrate many facets of life. You find it hidden in a dark corner of your memory, in a scene from a movie you forgot the name of or a joke you so innocently laugh at.

In the first episode of SBS Arabic24’s new in-language podcast ‘Racism Within’, three Arab Australians delve into how the scourge of racism is evident in their daily lives.

Wijdan Osman, of Eritrean origin, Amin Al-Jamal and Yassin Judeh, of Sudanese origin, discuss how communities can be victims of racism and perpetrate it at the same time.

“Yes, a black person can be racist against someone darker or even whiter, this is called colourism, we talk now about whites committing racism against us, yet we inflict this as well,” Ms Osman says.

Read more

Where will I be buried?

The three Melbourne-based community leaders believe stereotyping is common throughout the Arab world and within Australia, and is usually related to what certain nationalities look like – such as “knowing” the physical traits of an Iraqi, Egyptian or Lebanese person.

Mr Al-Jamal, an engineer and freelance journalist, says it is common for members of the Sudanese community in Australia to follow a colour system to describe members.

“According to Sudanese descriptions of colours and skin tones there are the red, white, yellow, green, blue and black. I am personally considered red,” he says.

Mr Judeh adds: “Some people believe that a light-skinned person is better than a dark one, or the opposite is true, so racism can be both ways and everyone faces the same challenges.”

‘Colourism’

Within the Arab community of Australia, “colourism”, or discrimination based on skin colour, is often closely related to the tribal systems seen in a person’s country of origin and is often used as a measure for belonging, power and wealth.

“If you are from Western Sudan you will know all your tribesmen and any outsiders will stand out, even if they lived in your region, you will still exclude them to preserve your authenticity,” Mr Al-Jamal explains.

Mr Judeh, a human rights activist who works with communities in the Western Sudanese region of Darfur, believes that European colonialism has also played a role in deepening this tendency among the tribes.

“The problem is historic, colonialism followed a divide and conquer strategy where they supported some tribes against others, and this created a historic injustice.

“These supported tribes developed a sense of ethnic superiority, and somehow this trickled to social settings and practiced in the same family where a light skinned child will be call Halabi ‘red’ and a dark one Zaroog ‘blue’.”

The issue has deep roots within Arab communities, which continues to this day and within Western societies, where identity and patriotism is measured based on skin colour, Mr Al-Jamal explains.

“What really hurt me is when I comment about my country and the uprising there, to be asked by my people are you Sudanese? Which tribe do you belong to? My answer is the same, I belong to any place and every part of Sudan,” he says.

Even marriage and relationships in Sudan are governed by the colour of someone’s skin, as Mr Judeh explains.

“Many love stories failed because of racial supremacy and generally, people from Western Sudan are looked down upon.”

If you think fair skin will protect one from racism, you are also wrong, Mr Judeh says.

“So sorry if I offend anyone but this is the reality, in Sudan they never use the term Halabi [red] in a positive way. If someone calls another Halabi, they want to degrade and humiliate you.”

Colourism is also evident within families, Ms Osman says, having witnessed many instances through her work in the field of child protection in Melbourne.

“I talk with kids a lot, young girls and teenagers face this a lot, a young girl told me how her mom often considered her less pretty than her light skinned sister…why?”

She believes that racism against women often reflects “standards of beauty” that are imposed by the society that don’t accommodate difference or diversity.

“I call this a barrier and a self-imposed intellectual restriction that women force upon themselves, please free your mind and think, Africans have their beauty, Asians have their beauty, Westerners too as well as Arabs, so why do we all need to look the same?”

Colourism also factors into important ceremonies. An example, as Ms Osman explains, is seen during a woman’s wedding day, where they are often asked to be “brighter and whiten up a little”.

After her wedding in Australia, she visited Sudan to show her relatives a video of the happy occasion.

She says they were shocked by what they saw.

“They saw all the girls in their natural skin tone and none of them used whitening creams or products, they asked how come they all came like that.

“I said they are beautiful, happy and proud of themselves.”

Read more

I changed my Arab name to fit in

Finding solutions

A solution to rid the community of racism is to identify the problem, Mr Judeh says.

“I am proud of being black, being Sudanese and I believe people are equal regardless of colour…and I feel pity for racists.

“We blame ourselves first and then blame regimes that institutionalized these norms… our societies still live in tribal wars ignited when someone loves another from a different tribe.”

It’s a sentiment shared by Ms Osman.

“Why do we let ignorance, corrupt media and dying norms control us? Why can’t we learn a little bit about others? Racism is a disease and a mental shackle that restrains your mind and blinds you.

“You can’t see the beauty and creativity around you or benefit from them, you can only see the colour of the person.”