Since Mustang won the prize for best European film at the 2015 Cannes Film Festival's Directors’ Fortnight, Deniz Gamze Ergüven’s directing debut went from strength to strength. The Turkish-language film became France’s Oscar entry over the likes of Jacques Audiard’s Palme d’Or winner, (even if no film was going to win the foreign Oscar over László Nemes’s Hungarian masterwork, ). Ergüven then won major accolades in the French Césars, taking out the best first feature César, with Australia’s Warren Ellis winning the music award for her film.

Ergüven was raised and educated in France before returning to Turkey to make her first feature, with its female-centric story of disgruntled teens forced into arranged marriage. The production struggled to raise finance at first and when Ergüven announced she was pregnant, her principal French producer bailed.

The thing the girls want is very simple: freedom.

When it seemed like the film would not go ahead, Olivier Assayas, one of her teachers at France’s premier film school, La Fémis (think AFTRS), who had personally chosen her for the prestigious directing program, put his former student in touch with his own producer, Charles Gillibert. Gillibert backed Ergüven all the way – right onto the Oscars red carpet, a place he had never frequented for the films of Assayas (Clouds of Sils Maria) or Assayas’ then-partner, Mia Hansen-Løve, whose films, including Eden and Things to Come (which won for best director in Berlin) he also produced.

Ergüven has been hailed as the Turkish Sofia Coppola for creating a kind of Turkish Virgin Suicides in Mustang. Yet the comparison is not quite right. Where Coppola’s sisters in her 1999 film were depressed, lackadaisical and doomed, Ergüven presents five self-possessed orphans who rally against the restrictions that have been enforced upon them in a conservative Muslim society after they innocently play with boys on a beach in contemporary rural Turkey.

They have their mobile phones and computers confiscated, they are locked in a house that is boarded up and one by one, they are forced into arranged marriages. In many ways Mustang, named after the wild horses with long manes like the girls themselves, is a jailbreak drama.

“The thing the girls want is very simple,” explains Ergüven. “It’s freedom. When you see them in the film it’s difficult not to have empathy with them and I guess even people who find problems with this film can find empathy.”

Ergüven has been bombarded with women telling of similar repression, arranged marriages and sexual abuse, from the likes of Korea and even Sweden.

“The film is more universal than I would have thought,” she admits, "and it has been completely embraced by France. It's a way for them to embrace me as being French with different origins and accepting the complexity of my culture and my identity.”

Mustang was mostly shot in a Black Sea village near where Ergüven’s paternal grandmother was born. “My grandmother was an orphan and she made my father study to further himself and he became a diplomat.” Her parents did likewise with her, even if it meant not spending a lot of time growing up in Turkey.

Ergüven was born in Ankara into a largely secular Muslim family and had moved to Paris as a baby when her father was posted there. She only lived for a few years in Turkey between the ages of nine and ten before she returned to France. She was educated at international schools and studied for a masters’ degree in African history in Johannesburg.

It was only in her 20s that she realised her passion for movie making and studied at La Fémis.

After graduating she became determined to make an American feature and spent over three years in Los Angeles developing a big budget production called Kings about the Los Angeles riots, though she failed to get it off the ground. When she attended the 2011 Atelier of the Cinéfondation in Cannes, a kind of think tank for developing projects, she decided to put the American project on hold and proceeded with Mustang.

I really didn’t want to portray the girls as victims.

She already had written a treatment and would co-write the screenplay with Alice Winocour, who was also at the Cannes workshop and would go on to make her own film, 2012’s Augustine, in which Ergüven would appear. Ultimately Ergüven was given the go-ahead for Mustang.

“It reassured people because unlike Kings, which was about five days in LA without laws, the characters are so close to me and they thought that I knew what I was doing.”

How did she cast the girls, who ranged in age from 13 to 21, and all but one of whom were first-time actors? “It took months. I saw hundreds and hundreds of actresses and it was really about having the right combination. Then one day it just clicked and the group started living and breathing like one body. I always thought about the film in a way that the five girls were like one body with five heads. In some ways it’s like this little monster with ten arms and ten legs.” It was important to have humour in there too. “I really didn’t want to portray the girls as victims. It was very important for me to have powerful female figures. They had to be solid, full of life and joy, figures of youth who others could aspire to. I think about them as being like James Dean. He was a figure opposing the status quo and brought this image of youth and beauty and strength that people could identify with.”

It was important to have humour in there too. “I really didn’t want to portray the girls as victims. It was very important for me to have powerful female figures. They had to be solid, full of life and joy, figures of youth who others could aspire to. I think about them as being like James Dean. He was a figure opposing the status quo and brought this image of youth and beauty and strength that people could identify with.”

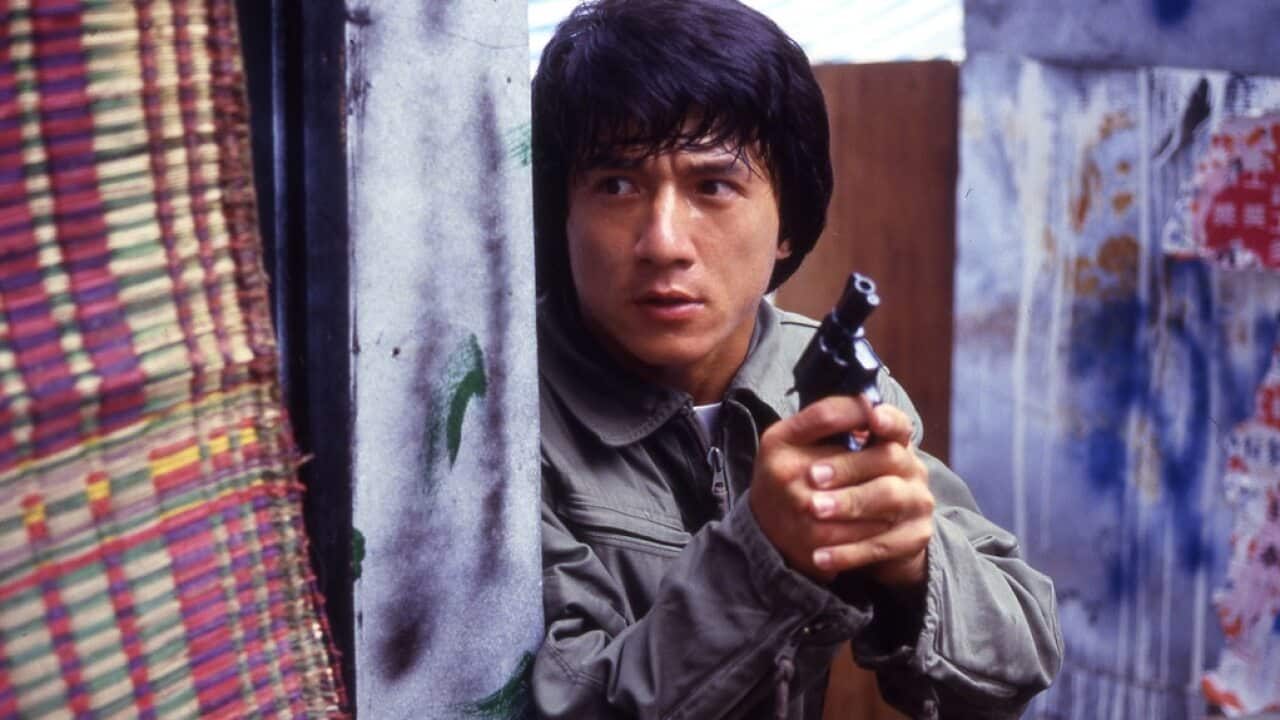

Mustang (2015) Source: Madman Entertainment Pty Ltd

Afraid to say too much about herself because of the sensitive nature of her film, Ergüven today does not discuss her religion or the nationality of her husband though she is admittedly content as the mother of a bouncy boy.

Ergüven had been the youngest in her extended family and appreciates that the youngest can learn from their siblings and cousins and lash out more as the Lale character does in the film.

“She is building from their experience. She is the hope for the future I think.”

Turkey has not always been as conservative as it is now, Ergüven notes.

“There have really been some very modern peaks. Women voted as early as the 1930s but at the same time it’s always been very patriarchal and quite conservative. Nowadays it’s becoming more and more conservative. Since 2002 we have a religious political party in power and they are trying to make Turkish society more and more conservative. While you have very free women in Turkey you also have women who are very much victims of honour crimes and arranged weddings and have all sorts of limitations to their freedom.”

She admits there are two very different sides to the country, which is somehow caught between eastern and western traditions.

It's a very vigorous country, you can feel it when you arrive that the population is very young and very powerful.

"You have the impression that Turkey can balance in one way or another according to what’s going on. It's a very vigorous country, you can feel it when you arrive that the population is very young and very powerful. You have the impression when you are in the heart of Istanbul you have central avenues which are crowded with people and there are cafes on four or five floors where there are a lot of people until early in the morning. There are political protests of different kinds every 200 metres and you have the impression the country is very hot and pumping with people. It can go in a lot of different directions.”

Despite the potential danger she sees in Turkey today, Ergüven plans to make her next film there, as she told . “If Mustang is about what it is to be a woman, the next project is about a couple, and the theme of the film is losing democracy.”

Watch 'Mustang'

Monday 30 August, 7:40pm on SBS World Movies (Streaming after at SBS On Demand)

Tuesday 31 August, 11:45am on SBS World Movies

Wednesday 1 September, 1:20am on SBS World Movies

Tuesday 31 August, 11:45am on SBS World Movies

Wednesday 1 September, 1:20am on SBS World Movies

M

Turkey, France, 2015

Genre: Drama

Language: Turkish

Director: Deniz Gamze Erguven

Starring: Güneş Nezihe Şensoy, Doğa Zeynep Doğuşlu, Elit İşcan, Tuğba Sunguroğlu