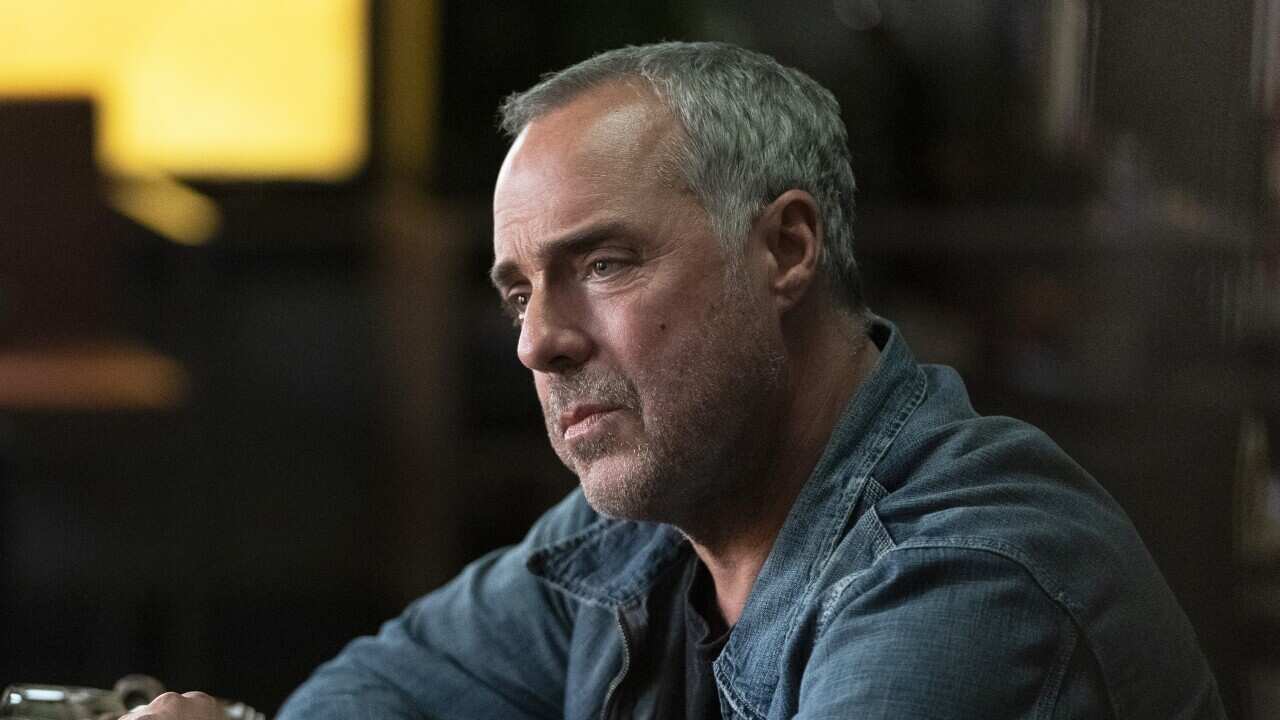

Walkley Award-winning journalist and documentary filmmaker, Extreme Engagement reality TV show star and all-round adventurer Tim Noonan has spent his professional life exploring some of the remotest spots on the planet. But it was at home in Tasmania that the cinematographer on SBS hit and one-man producing team (when not accompanied by his wife and Wildman Films partner PJ) finally turned to the most incredible adventure of all.

“Any filmmaker who grows up here is fascinated by the story of the Tasmanian tiger,” he says. “I moved away, became a journalist, travelled the world, and then left news and current affairs to pursue my passion for documenting all the things that were going to go extinct. So when PJ and I got married, came back and we had a baby here in Tasmania, it felt like the time was right to tell this story.”

The thylacine was known for its distinctive stripes. Credit: Tim Noonan / Wildman Films

The Tasmanian tiger, AKA thylacine, was a striped carnivorous marsupial that once stalked the island for its prey, largely consisting of small birds and mammals. Tragically, it was hunted to extinction after colonial invasion, with the last of its kind – named Benjamin – dying a cruel and lonely death held in captivity at Beaumaris Zoo in Hobart on September 7, 1936.

But was that really the end? Noonan’s not so sure. His new two-part documentary series Hunt for Truth: Tasmanian Tiger finds him heading to Tassie’s remotest corners and travelling to Papua New Guinea, where he faced a kidnapping threat in search of answers. The thylacine once lived here too and local communities deep in the rainforest insist it still does.

“People love the unsolved mystery, like a true crime story that pulls you in, searching for answers,” Noonan says. “Because there’s a very real and legitimate chance that it’s still out there. It’s not like looking for the Loch Ness monster or Big Foot. This animal really existed.”

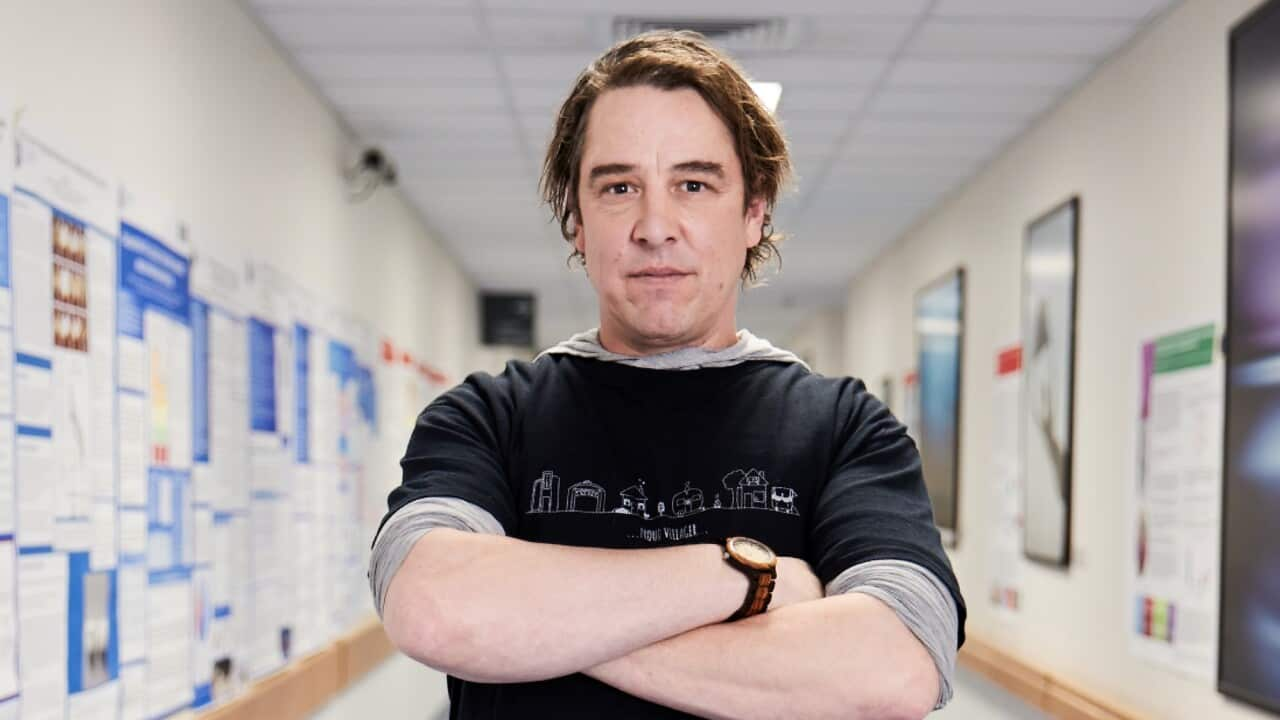

Tim Noonan interviews environmental scientist 'Tigerman', who says he saw a thylacine in 2002. Credit: Tim Noonan / Wildman Films

We don’t have an excellent track record on eliminating species. “There’s something like 200 species of animals and plants that go extinct around the world every day,” Noonan says. “There are people actually trying to de-extinct the thylacine.”

Indeed, in a Jurassic Park-style move, some scientists hope to clone the thylacine from the broken DNA chains of Benjamin’s remains, splicing him with related species, the dunnart. “But it’s a hybrid. It might look like a thylacine, but there’s a big unknown. If they succeed, it might do what the thylacine did in the ecosystem, but it might not.”

Using colourisation techniques on the grainy old footage of Benjamin’s grim enclosure brought home the scale of the loss for Noonan. “When I saw it in colour, it dawned on me that we’ve lost a really unique animal, and I can understand how people become so obsessed with finding it.”

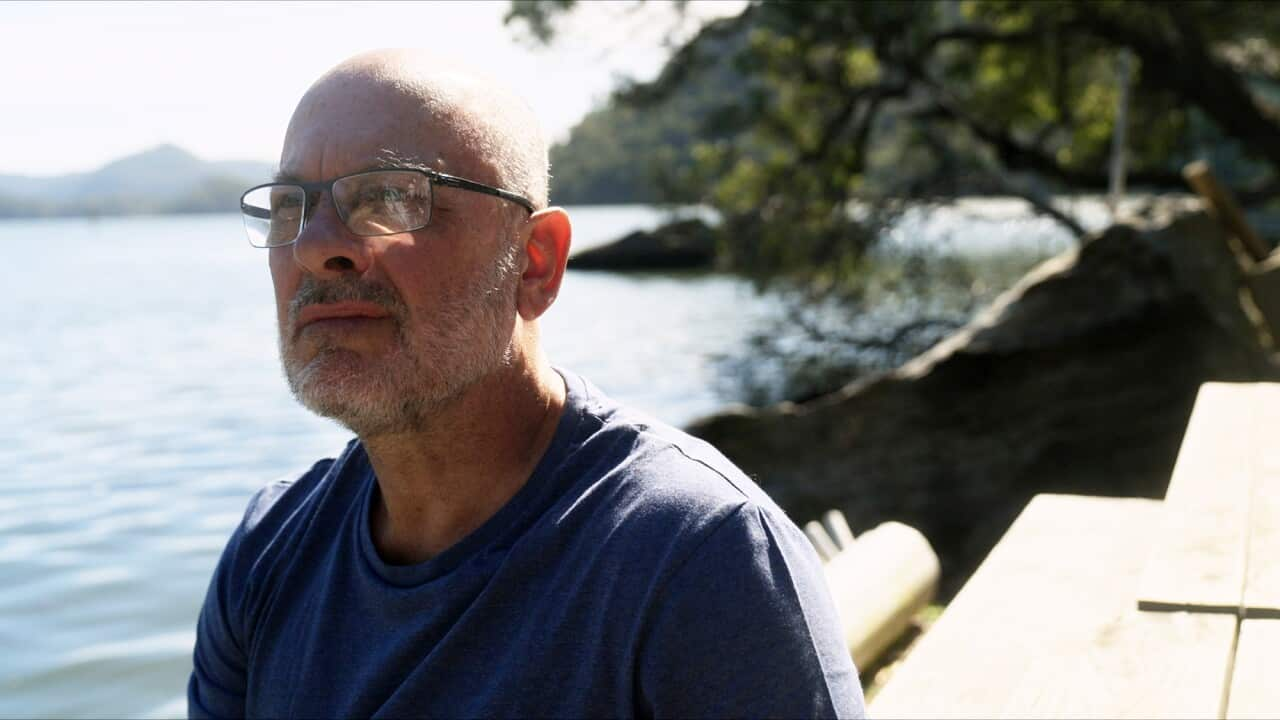

Quite aside from the oft-ridiculed private citizens who have spent inordinate amounts of time and money in search of the tiger, Noonan meets experts at the University of Tasmania who are also on the case. They include Laureate Professor Barry Brook. One of the world’s leading authorities on the thylacine, he has overseen a colossal endeavour, posting cameras across the island to monitor wildlife, which also cover locations where there have been reported sightings of the tiger.

Looking for the truth: Professor Barry Brook. Credit: Tim Noonan / Wildman Films

“One of the key reasons that the university is looking into this is because the searches that have been done in the past haven’t been meticulous,” Noonan says. “They’ve only had a handful of cameras and might have only searched for a couple of weeks at a time in tiny pockets throughout Tasmania.”

Noonan was exhilarated by Brook’s belief that a colony of thylacines could have survived in Tassie’s southwest corner. “He’s convinced, having evaluated and ranked all the sightings since 1936, that there's a small chance they survived up until the 1980s, possibly even till the early 2000s.”

At that point, Brooks fears that the unforgivable may have happened again. “Essentially, we let it go extinct twice because we didn’t activate ourselves to try and save it,” Noonan says. “I feel like we’ve really let this creature down.”

Isn’t there an argument, then, that if a colony somehow survived in Tassie or the most inaccessible corners of the islands of New Guinea that we should stay the hell away, so we don’t do it a third time?

“This is the whole conundrum of this story: if we were to rediscover it out in the wild, as a documentary filmmaker or scientist, should you then tell the public?” Noonan asks. “Because it would surely open the doors to a whole lot of fringe tiger hunters and people that you wouldn’t want looking for the tiger, compromising that remaining population.”

Tim Noonan with a University of Tasmania researcher, inspecting potential denning sites. Credit: Tim Noonan / Wildman Films

A dilemma, to be sure, but Noonan suggests looking at the risk from another angle. “There’s an army of people in Tasmania that say you should just let it breed in peace if it’s still out there, but I’ve come to realise that that’s a really flawed argument,” he insists. “Having spoken to all the scientists, they underline that you need a certain number of individuals to keep it going. What if there were only 100 Tasmanian Devils left? People would be up in arms, activating to protect them. And yet we almost certainly let this animal go extinct twice and just turned a blind eye.

“If we were to do that again, wow, that’s shocking .”

Noonan has poured blood, sweat and tears into this search, and it’s not over yet. He needs answers. “I'm determined to get there and at least close the book in my own mind.”

Hunt for Truth: Tasmanian Tiger premieres on June 12 at 7:30pm on SBS, with part two airing on June 19. The documentary will also be streaming .

Stream free On Demand

Hunt for Truth: Tasmanian Tiger