One of the first songs I remember hearing as a kid was NWA’s F##k Tha Police. My brother used to play it on his boombox loud enough that it could be heard a few houses down our street in Sydney's Marrickville. This was the era of TDK cassette tapes, the Sony Walkman, big hair and Stallone-Schwarzenegger films. The 1980’s and early 1990’s was prime time for hip hop, the so-called “golden age” - where artists like Public Enemy, Eric B and Rakim, Grandmaster Flash, Big Daddy Kane and NWA pioneered socially conscious rap, scratching, drum beats and artful MC-ing.

Albums like Public Enemy’s Fear of a Black Planet and It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back are still considered to be some of the most poignant critiques (if not indictments) of white America, tackling issues such as systemic racism, police brutality, gun violence and media hype. Earlier in the 1970’s artists like Gil Scott-Heron released spoken word tracks such as The Revolution Would Not Be Televised and The Sugar Hill Gang’s Rapper’s Delight was one of the first rap songs to get mainstream play.

Rap music for me is about being true to yourself, unafraid, and invariably questioning, or as rappers would put it “keeping it real”.

Rap and hip-hop has always been a part of my musical palate, and has become even more so as a I find myself reflecting on my social, cultural and religious background as a Lebanese Arab Australian Muslim. Rap was originally a means to enlighten, educate and empower through lyrical storytelling. It was a musical genre that artists used to challenge and express ideas about politics and power. It was and still is a creative space where outcasts and the disenfranchised could find their voice, a voice that has been struck silent by the invisible hand.

As an Arab Muslim in a post 9/11 world, the status of the political and cultural outcast has taken centre stage in my life, if not thrust upon me. My distrust of the American establishment, its “democratic” imperialism runs in tune with Tupac’s lyrics in Trapped and Words of Wisdom —songs that resonate with the trials I have faced growing up as part of a minority in Australia, that sense of alienation, inferiority and imposed conformity. I shouldn’t be told who to read and what is socially acceptable writing. What NWA did with F##k tha Police and Straight Outta Compton was let artists and minorities know it was okay to be themselves, to not blindly and uncritically conform, to not turn the other cheek.

Lebanese people are seen as an undesirable minority within the Australian project, a project that finds its disingenuous heritage in whiteness and Judeo-Christian values or “civilisation”. And whatever that means we know we are not a part of it.

What NWA did with F##k tha Police and Straight Outta Compton was let artists and minorities know it was okay to be themselves.

Arab Muslim voices are not being heard in Australia. We are excluded, we are silenced. Or as Ghassan Hage puts it in his book , “we are but objects to be moved around at will by white multiculturalists and white nationalists within the fantasy of the white nation”. We are either segregated as cultural political outcasts or “tolerated”. Young Arab men in that sense can relate to the black experience in America; it speaks to us, and no more loudly than through rap music and hip hop. Ghettoisation happens in Australia just as it does in America. One only needs to look around multicultural Australia to find suburbs that are majority Arab, Muslim, Turkish, Asian or Indian. Or white and Jewish for that matter.

I didn’t grow up in the western suburbs of Sydney where Arabs are generally known to reside, yet I still developed a ghettoised mentality by virtue of being Lebanese. I’ll give you an example of what I mean. In 2006 a local I knew in Kings Cross, where I had been living and working, told me to stay away from Cronulla during a time that would come to be known as the Cronulla Riots. I had been in Sydney about six years then and I had never been to Cronulla. I never travelled that far south of the city. The images of “Middle Eastern” looking men getting bashed on trains or racists given airtime on TV isn’t something that escapes your mind easily. Simply by being Lebanese I was somehow connected to this geographical location where violence was being perpetrated. These realities played on my mind, I was othered just like those Muslim Arab males in the western suburbs. I couldn’t escape my other Australian identity.

The racism that Arab Muslims were experiencing is similar to what black artists were rapping about—exclusion, criminal profiling, stereotyping and negative media coverage.

Added to this heightened sense of scrutiny as a Lebanese Australian Muslim was reading words like “Middle Eastern gangs”, “Middle Eastern organised crime unit” or “Muslim terror” plots in daily newspapers. The racism that Arab Muslims were experiencing is similar to what black artists were rapping about—exclusion, criminal profiling, stereotyping and negative media coverage. They spoke to our experience. Many of these American rappers themselves have some connection to Islam or Arab culture whether through the Nation of Islam, African ancestry, or being Arab or Muslims themselves. Rappers like Rakim, Nas and Mos Def (Yasiin Bey) all cite Quranic scripture in their raps. On the production scene you have people like DJ Khaled, Noah ‘40’ Shebib, and Fredwreck who have Arab roots.

The cultural forms that rap and hip-hop music take is not alien to the genre of Arabic music. The modern day cipha or battle can be seen in traditional forms such as Lebanese Zajal where poets try to outdo each other in rhyme, folklore and lyrical wit. It is not unusual to switch on Lebanese TV and find poets performing Zajal or Ataabah. They are held in high esteem and are part of the Arab memory. The Arabic language itself is heavy with natural lyricism and homonyms that flow like a Jay-Z hook. Arabic is a protest language just like original rap was.

They too practice a certain protest masculinity just like rappers spit, because most are powerless, poor and policed.

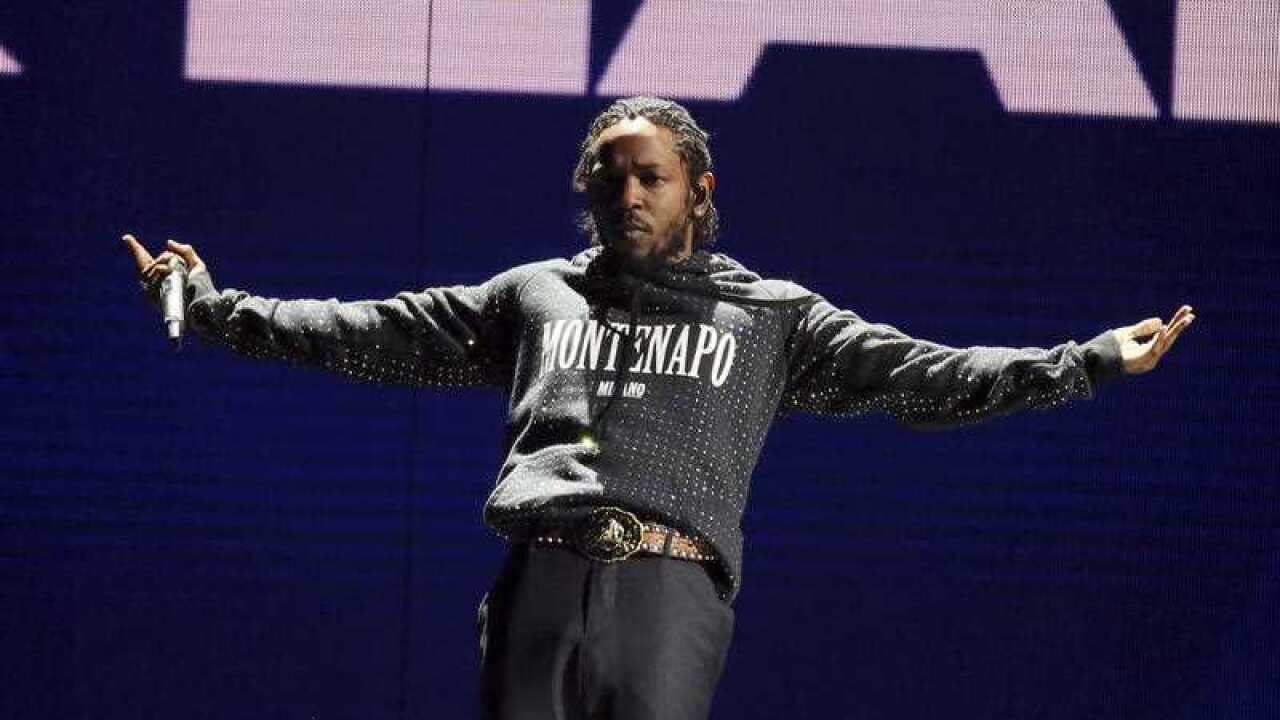

My Arabic is my rap, it is a protest against the establishment at a time when Arabic is demonised as the language of terror. When singers like Drake say “It’s a habeebi ting” or Mos Def opens up tracks with the first words of the Quranic Fatiha: bismillah al rahman al rahim; or when Kendrick Lamar raps about praying to Allah there is a sense of shared experience that I find in their lyrics.

This genre of music is resonating with hip-hop heads worldwide, and just like Muslims have the Ummah, many Arabs today are part of the Hip Hop Nation, a global trend that has localised rap to suit one’s culture and time. In Israel the Palestinian hip hop group DAM are rapping in Arabic. With songs such as I Don’t Have Freedom and I’m Not a Traitor they are mixing Arabic instruments with rap styling, spittin' about injustice, poverty, occupation, geopolitics and Arabism. Other artists like the British Iraqi rapper Lowkey have released hard hitting intellectual tracks like Obama Nation, Hand on Your Gun, and Terrorist which address capitalism, imperialism, arms dealerships and warfare. Arab artists are practicing the basic tenets of rap which seems to have lost some of its intellectual sting with the arrival of Gangster Rap. But even in the sub-genre of Gangster Rap many Lebanese youth in Australia have found the music resonates with their experience as marginalised minorities. They too practice a certain protest masculinity just like rappers spit, because most are powerless, poor and policed intellectually and socially. Rap music for me is about being true to yourself, unafraid, and invariably questioning, or as rappers would put it “keeping it real”. Keeping it real is the freedom from intellectual conformity, social quietism, and cultural hegemony. So, keep it real ya’ll!

Shout out to all the hip hop heads! Salaam.

Daniel Sleiman is a freelance writer. He is currently working on his first novel. You can follow Daniel on Instagram at .