I learned a lot in school, enough to get into university, but my most profound discovery was that Dad was an immigrant. I had no idea he was. I thought he was Australian, until Year One when a blond boy with curly hair and a peeling nose told me I was wrong. “Australians come from Australia. He’s from China,” he said.

The thing is, Mum is Scottish. And she ran our house as if we were Scots. Baptised as Presbyterians, we ate porridge and pudding even though we lived in Proserpine, a hot and humid farming town in North Queensland.

She was the immigrant, not him.

Dad did what the other Australian men up there did, which was go to the pub. He was a football-loving, beer-drinking bloke who fished and farted and spoke North Queensland strine. That was the currency all the blokes traded in at the Palace Hotel where there was a rowdy, humorous atmosphere. As a teenager, I used to go there with Dad and play Galaxian while he drank. Sometimes I heard jokes being told at his expense. One man would greet him with, “G’day, China!”

He was a football-loving, beer-drinking bloke who fished and farted and spoke North Queensland strine.

Although he was treated as such, Dad was far from fresh off the boat. His family arrived in the 19th Century. They signed an allegiance to Queen Victoria and the colony of Queensland as required by the Aliens Act of 1867. They put down generational roots in Townsville and Innisfail. His was one of the first families to colonise the region.

Mum’s family emigrated to Australia a hundred years after Dad’s, during the 1950s on a ship from Edinburgh. So-called “ten-pound poms”, they moved into the house next door to him. That’s how Mum and Dad met. She was 18, he was 30. When their relationship bloomed, my Scottish grandad, who fought the Japanese in the Second World War, couldn’t abide his daughter falling in love with an Asian so he swiftly relocated the family to Brisbane. Mum was unhappy about that so she eloped, and went back to Innisfail where she lived with Dad’s family until they could marry.

Dad didn’t pursue his Chinese culture. He cooked an occasional sweet and sour pork and once gave us salty plums, just to watch the reaction. We screwed up our faces. He taught us how to use chopsticks. I suppose that’s all that was left in his cultural bag after his family had integrated through four generations. No one spoke Mandarin or Cantonese. Dad was baptised as a Catholic and he went to a Marist Brothers school. Even our family name was veneered. Dad told us it was French. But after he died, his sister, my Auntie Merle, researched our original Australian ancestor. In the state records she discovered a misnomer. My great great grandfather, a colonial market gardener by the name of Pan Min On, had his family name changed on his arrival. Because Chinese naming conventions were misunderstood in Australia at the time, his two-syllable given name, “Min On”, was assumed to be his family name. When he was taught how to write it in English, the mistake was set in stone.

Even our family name was veneered. Dad told us it was French. But after he died, his sister, my Auntie Merle, researched our original Australian ancestor. In the state records she discovered a misnomer. My great great grandfather, a colonial market gardener by the name of Pan Min On, had his family name changed on his arrival. Because Chinese naming conventions were misunderstood in Australia at the time, his two-syllable given name, “Min On”, was assumed to be his family name. When he was taught how to write it in English, the mistake was set in stone.

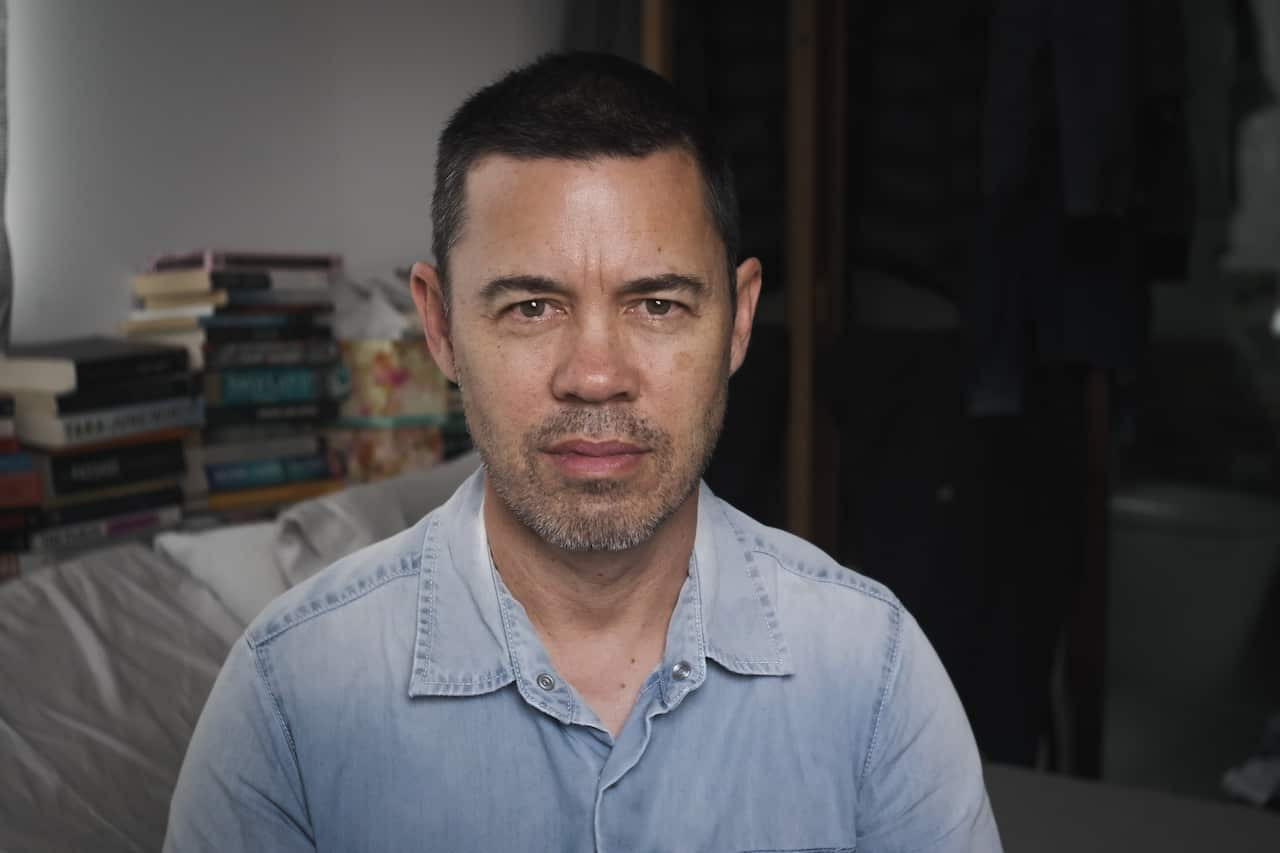

Writer Steve MinOn. Source: Steve MinOn

Today, when people pronounce our name, they make a different mistake: they say “my-non” instead of “min-on”. Sometimes they say “minion” after the animated character, or “mignon”, after the French word, which may explain how Dad developed his version of the story. It would have been easier if our actual ancestral family name had been used, “Pan”.

I never heard Dad object to the idea that he was considered the immigrant of the family, but I think he did a lot of overcompensating. Like in 1998, when he voted for Pauline Hanson. I asked him why. He said he agreed with her stance on ''. I couldn’t believe what I was hearing, and we argued. When I reminded him about her maiden speech on the “dangers of Asian immigration” he said he didn’t think she was talking about him.

When I reminded him about her maiden speech on the “dangers of Asian immigration” he said he didn’t think she was talking about him.

Back at school, when they taught us about ancient philosophers, specifically Confucius, the other kids found it funny to use this new-found knowledge to single me out. While I ordered at the tuck shop, they’d joke, “Confucius say sausage roll.” On the tennis court, it was “Confucius say double fault!” If I objected to being teased, they’d reply, “Confucius say stop it!”

I knew they were making fun of me for being part Chinese, but I couldn’t object because it meant denying Dad. I was conflicted by that through my adolescence.

Due to the fact that we were thought of as “the Chinese family with the White mum”, I’ve always felt more defined by my Chinese side. I tell people I’m mixed Chinese-Anglo but if you see more of one than the other, I’m whatever you see.

When I think about our family home, I remember it as a haven, somewhere I could just be a kid, rather than a curiosity.

When I think about our family home, I remember it as a haven, somewhere I could just be a kid, rather than a curiosity. I wonder how my childhood would have played out in a country where Chinese communities were the dominant cultural group. Maybe people would have asked where Mum’s family was from, instead of Dad’s. In Australia, Mum was an immigrant, sure, but hidden in plain sight because of how she looked. I asked her recently if she ever felt like the odd one out. She said no. I said, what about in our family? She had to think about that one.

This article has been published in partnership with Sweatshop: Western Sydney Literacy Movement.