For the most part, the pounamu (green stone) that my birth father gave me sits in a special wooden box tucked away safely. In times when I feel that I need strength or feel my resilience waning, I put it on and it makes me feel fortified.

I was adopted in Australia in 1980 after my birth mother travelled from New Zealand to give birth to me. Adoption is usually characterised as either ‘domestic’ or ‘intercountry’. I fall into a somewhat unusual category of being born in Australia but having ties, however thin, to another country and culture just across the ditch.

The paperwork and tid bits of information that my parents were given about me when I arrived was slim to none. Among the skerrics of information I had to shape my identity, the most concrete were my birth mother’s first and maiden name and a note that my birth father, unidentified in the paperwork, was Maori.

Travelling to New Zealand in 2000 to meet my birth parents for the first time was a transformational experience. I met them in the time before Facebook without even exchanging photographs. I walked out firstly at the airport to meet my birth mother, and then a week later, I stepped off a minibus to meet my birth father and his family.

My birth father and his family made me feel so welcomed. It meant so much to be introduced to his mum and close friends. He made a hangi in my honour. I still kick myself that I only ate the vegetables and declined the smoky, earthy meat. I was in a vegetarian phase and in my youthful naivety I put my new-found and relatively short-lived ideals above this grand gesture of love and cultural connection. I also regret taking a ‘special’ although completely corked bottle of wine to share with my birth mother!

I was in a vegetarian phase and in my youthful naivety I put my new-found and relatively short-lived ideals above this grand gesture of love and cultural connection.

It wasn’t until I went to university, lulled into a sense that I was surrounded by progressive openness and understanding, that I mentioned my Maori heritage in a tutorial. My very esteemed and accomplished lecturer said in response “You’re not Maori”. Since then, I’ve been a lot more cautious about how I describe myself. With those who I trust I might share that my birth father is Maori. But I am conscious that I haven’t been socialised in the way that his children have been. Maybe my lecturer was right, maybe I’m not Maori. Either way, I don’t think it was her place to tell me what I am and am not.

Even though I ‘pass’ as entirely Anglo-Saxon and have benefited from a privileged life, I’ve always been hyper alert to racism and felt it viscerally, thinking to myself, “If I was growing up in New Zealand, that would be my family they are talking about.” I have benefited from white privilege because of my appearance and family of origin. I’ve also been spared the horrendous racism and insensitive remarks that some intercountry adoptees experienced. Now that I look back on the path my life has taken, through working in Redfern in Sydney as a youth worker and to working in Alice Springs and Darwin as a lawyer, it is clearer to me the subterranean rumble within that took me on those journeys. It was in those places that I have had some of the most memorable experiences of my life.

Now that I look back on the path my life has taken, through working in Redfern in Sydney as a youth worker and to working in Alice Springs and Darwin as a lawyer, it is clearer to me the subterranean rumble within that took me on those journeys. It was in those places that I have had some of the most memorable experiences of my life.

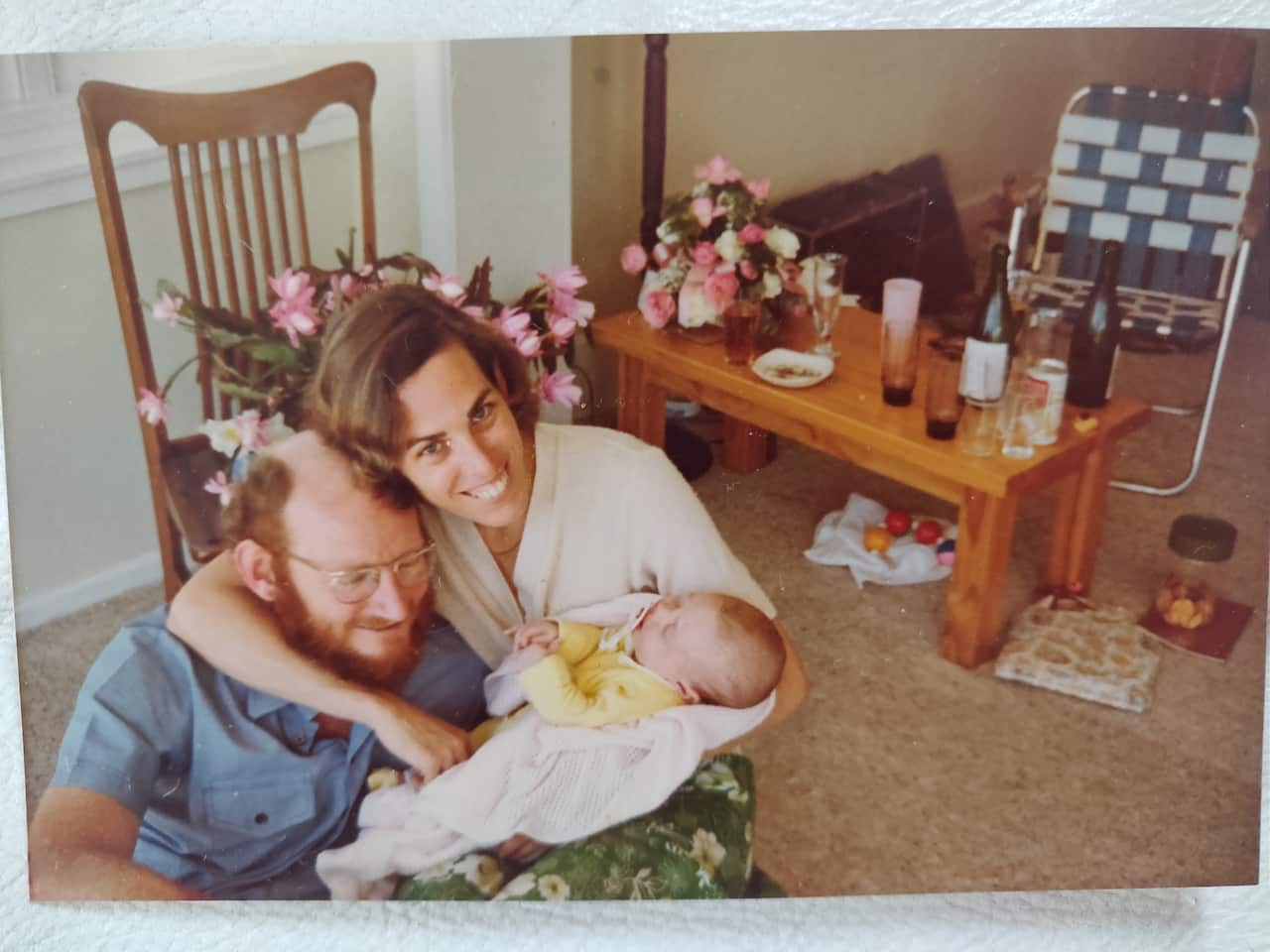

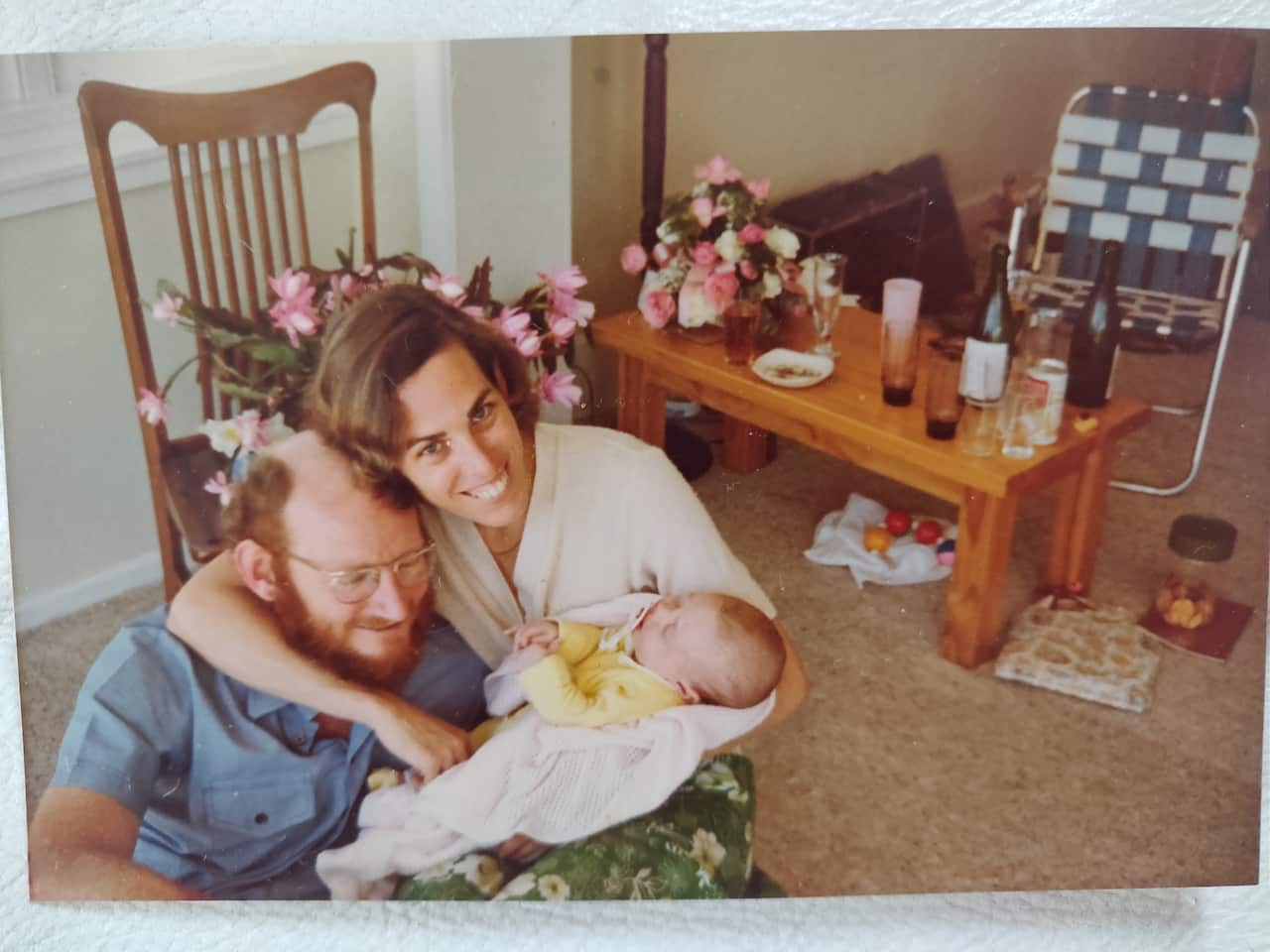

Mum and Dad celebrating my arrival at six weeks old. Source: Supplied

One such memory is listening to the heart stirring songs of Shellie Morris at Rungutjirpa, otherwise known as Simpsons Gap, just outside of Alice Springs. She shared her story of adoption, including the tragic experience of not being able to meet her father before he passed. My worst fear growing up was exactly that - that when I went looking for my birth parents, that I would be too late. Hearing this hurt spoken out loud brought me to tears.

My worst fear growing up was exactly that - that when I went looking for my birth parents, that I would be too late. Hearing this hurt spoken out loud brought me to tears.

That experience was powerful for so many reasons. Primarily because I really hadn’t met many adopted people or heard people speaking about their adoption experience openly up until then. It was of course amplified by the experience of sitting amongst a cathedral of crags, nestled against part of the West MacDonald Ranges on the sand.

For some, songs are a form of storytelling. For me, I have always loved to write. When I had my first child, I decided that it was ‘now to never’ to realise my long-held dream of writing a book. Fast forward almost five years, and the result is, We Love You Hundreds and Thousands. Ostensibly, it’s a colourful picture book about fabulous birthday parties. It is also a book about a diverse family and belonging.

I really wanted to write a book that would enable children who are fostered and adopted to see themselves in their bedtime story and to have a way to share their family with others. Doing the classic ‘family tree’ exercise at school can still be difficult for children who don’t come from a nuclear, heterosexual family. I’m hoping this book brings to life another family structure that can help reduce stigma in classrooms and households around the country.

Maya Angelou famously said, “The idea is to write it so that people hear it and it slides through the brain and goes straight to the heart.” It is my hope that this book transforms a few hearts.

I purposely wanted to make the book feel celebratory, but I’m also incredibly conscious that the experience of foster care and adoption for many children is far from jubilant. I also know that there are far too many Aboriginal young people in out-of-home care for a range of deep, complex structural and systemic reasons. So I partnered with ID.Know Yourself to provide some proceeds from the book to advance their work with Aboriginal young people in out-of-home care and in contact with the justice system.

To be adopted is to experience a defining sliding doors moment. For some, it can dramatically shift the country and culture that they grow up in. At this mid-point in my life, I still want to find out more about where I come from and continue to strengthen my connections across the ditch, not only for myself but also for my children.