Technically, I’m disabled. I’ve been diagnosed as autistic, alexithymic and anxious. Previously, therapists told me I was depressed and suffering from an adjustment disorder. Before this, it was an eating disorder and, prior to that, I was described as obsessive, manic, overly sensitive and analytical.

It’s taken me years to come to terms with all the conditions I’ve been told I possess. There are so many negative connotations and forms of stigmatisation that go with them. Yet, somehow, through embracing disability and mental illness, I feel more empowered than ever. I no longer have to hide, or pretend. Everyday it’s “hello world, this is how I think and feel, apparently I’m disabled, what up?”

And lately I’ve been wondering how it is that I’m so damaged, injured and incapacitated. I might be taking the whole thing too literally - I mean, I’m supposedly impaired in that regard. It’s just that I’d respect the idea of being disabled a bit more if when I looked at other people’s daily activities and interactions I saw something functional. The problem is that I don’t.

People in the modern world aren’t radiating health, wellbeing or autonomy. They’re working too much and too hard under the assumption that they can manage their workloads and lifestyles, although none of them seem to know what it means to care for their bodies, finances, families, friends, communities or planet.

They’re unable to sleep, or think straight. They have no idea what they feel and when asked how they are they say non-descript things like, “busy”, “fine”, “stressed” and “ok”.

To let off steam they binge drink, smoke, watch porn, do drugs, shop, channel surf, scroll a feed, troll, road rage and speed. Then they worry about money, because letting off steam is expensive. So they become fixated on the next job, contract, paycheck or meeting. To quell the anxiety of this, they live for vacations and long for the day when they aren’t where they are. And if vacay isn’t an option, they eagerly anticipate the next opportunity to numb out on party drugs, painkillers and prescription medications.

Because the body, heart and mind are in pain and no one is listening. Instead, they’re smiling when they want to scream and saying yes when they want to say no. They’re unable to sleep, or think straight. They have no idea what they feel and when asked how they are they say non-descript things like, “busy”, “fine”, “stressed” and “ok”.

People believe that having adverse reactions to modern life and its demands – meltdowns, panic attacks, feelings of being overwhelmed, exhausted, listless, lonely and sick – means that they’re the problem, not it. And if they can’t keep up and abide by the that binds it together, they worry about being ostracised, fired, demoted, considered useless, or undesirable. So they build a wall of unreality around themselves and their tears and frustrations get hidden behind filters, forty character bios, fad diets, make-up and unnecessary cosmetic procedures.

Walking down the street they see someone in a wheelchair or with cerebral palsy and feel grateful for the fact that they aren’t them, seemingly unaware of the fact that modern life is a disability. They’re trapped within the confines of a system that has set them - and the planet - up for failure.

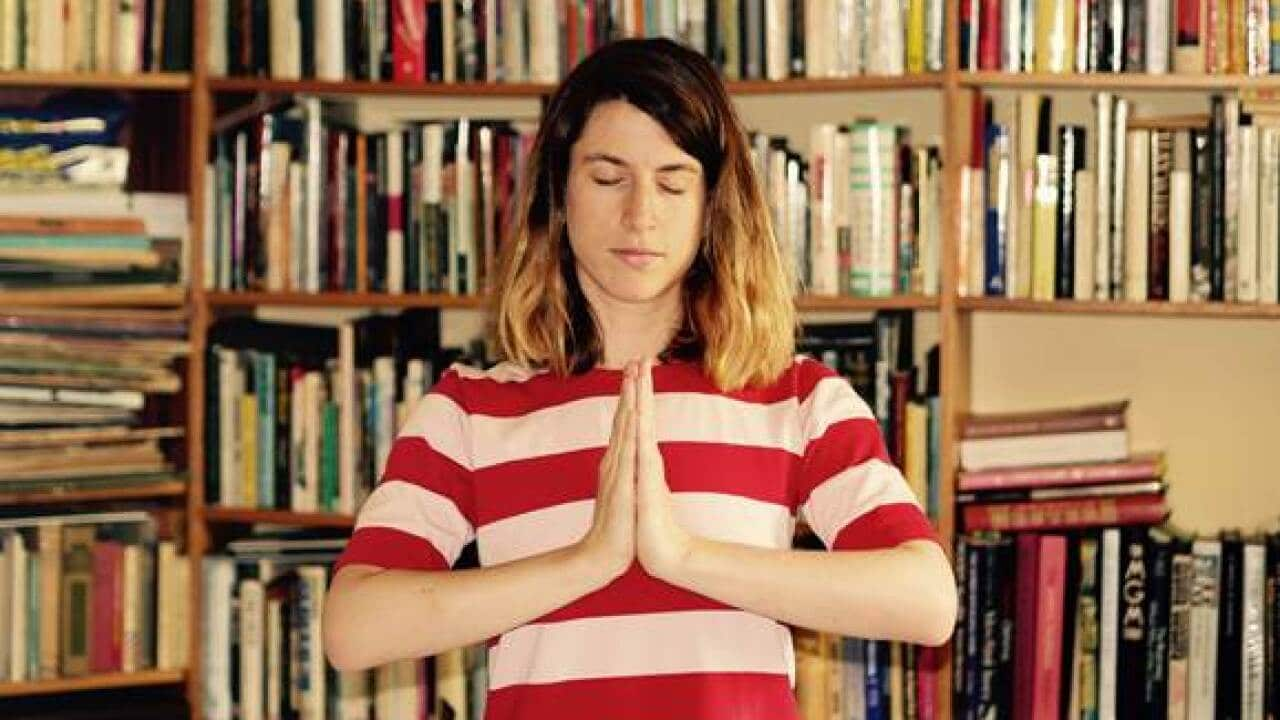

In the modern world there’s no time or space to simply be alive, and be human. Opting out or sitting down to meditate becomes a rebellious act because the phone must be off. Work has to stop. Others have to wait. Feelings might arise. Thoughts can be heard. The body might be hurting. Oh, no. What about work tomorrow? What about all the expectations and pressures and responsibilities that can’t possibly be managed in a healthful way?

Through accepting disability, and being open about it, I’ve learned about my limitations and how to share my needs and feelings.

Something is seriously out of balance when everyone knows that being in nature, exercising regularly, having a healthy outlet, sleeping well, limiting waste, eating plants, enjoying the company of those they love and turning off devices enriches their lives - and the life of the earth - yet they still don’t do it enough.

So the medical establishment might call my brain a ‘defect’ and an unfortunate ‘neurological predisposition’ and a ‘neurodegenerative disease’ and a ‘neurodevelopmental disorder’ that’s accompanied by a plethora of ‘co-morbids’ and ‘mental illnesses’ and none of it means much because something has gone ‘right’ through my being ‘wrong’.

Through accepting disability, and being open about it, I’ve learned about my limitations and how to share my needs and feelings. I constantly have to change, express vulnerability and risk being rejected. My life is defined by honest communication with employers, lovers, family and friends.

And when I encounter other disabled people in the street, I don’t see impairment. I don’t see dysfunction, or damage. I see the modern world’s last hope for a better day. Because, through us, everyone else can learn about what it means to live without fear.