Recently, mum was sitting alone at a restaurant and offered to share a table with a man, but had apologised in advance because she wanted to read and so wouldn't be too social. Sure enough, the man ended up interjecting and in the space of their quick meal, he managed to make assumptions about my mother, her career path and where she lived, lecturing her on how really, my family is "lucky to be here".

Over this meal of Malaysian comfort food, in a place where I call the owner Aunty, in the city I spent most of my life, I was taken aback that some people still found it fit to offer advice on how migrants can lift themselves up from their humble roots and have happy, fulfilling lives.

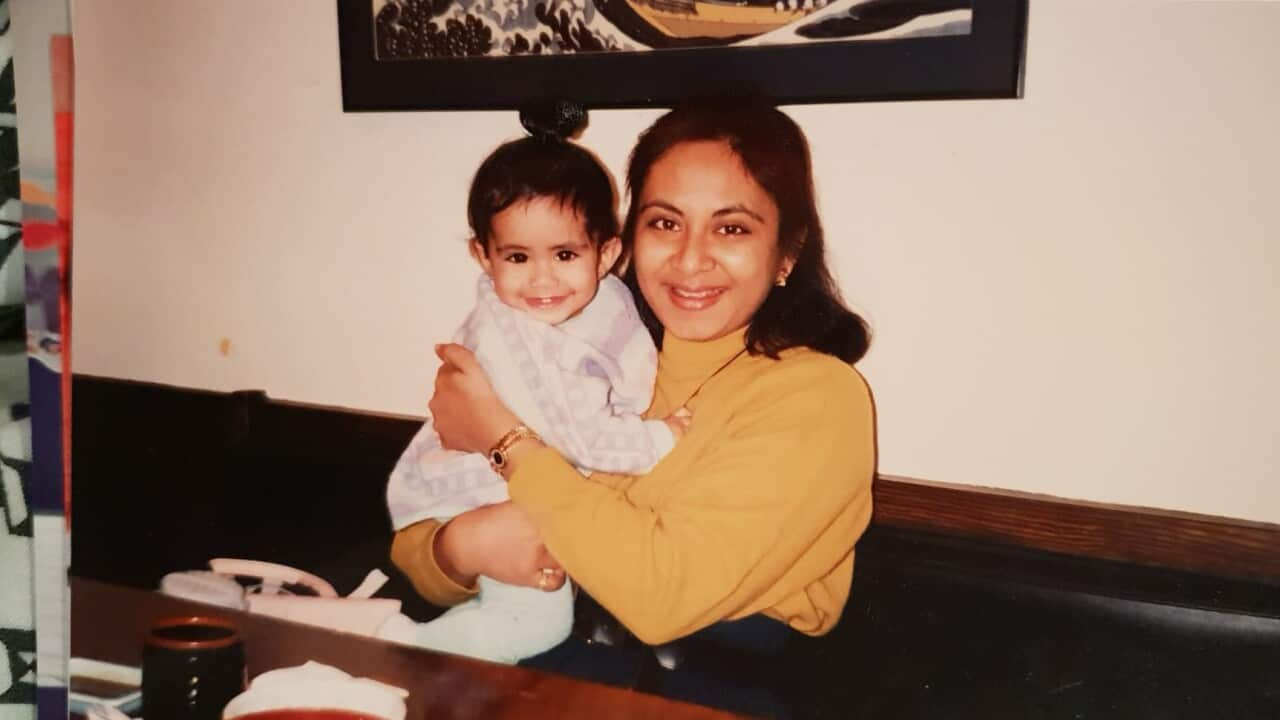

The article my mother was reading contained an interview with me. It was about my work, my sense of belonging and learning how to call Adelaide home since I left in early 2018. My mother, a busy GP who really only has time for herself if she can grab a meal alone, usually only has the time to read such things long after they have been released due to her schedule. In Malaysia, my mum worked as a surgical registrar, then a GP. Even though medicine wasn't her first choice (she wanted to go into the arts), she persisted through her studies and is now grateful as that education helped her leave an abusive marriage with my biological father and later on, allowed her to work here in Australia.

In Malaysia, my mum worked as a surgical registrar, then a GP. Even though medicine wasn't her first choice (she wanted to go into the arts), she persisted through her studies and is now grateful as that education helped her leave an abusive marriage with my biological father and later on, allowed her to work here in Australia.

In Malaysia, my mum worked as a surgical registrar, then a GP. Source: Supplied

When I sat down with my parents at 17 and announced that I was desperate to attend art school, they were distraught but supportive. My mother felt she couldn’t repeat the actions of her parents, so we made a deal where I still had to attend university after a year at art school. I excelled at art school which I loved dearly and struggled horribly through my bachelor’s degree in Architecture. I spent every free moment through my studies creating art and establishing my career, even forming a business at 23 before I finished my degree. I could see glimpses of success behind the failures of my “acceptable” tertiary education and my life since has been an internal battle of maintaining responsibility and respect for my parents while hunting for success in the least likely places.

On reflection, this is something of a 'reverse migrant dream' – where my mother achieved economic stability in an elite professional field, so that I may pursue a more economically volatile career in a creative field. It is a powerful feeling to not only buck the trend, but to undo any prejudice or expectation that I should follow suit in a traditional career path.

On reflection, this is something of a 'reverse migrant dream' – where my mother achieved economic stability in an elite professional field, so that I may pursue a more economically volatile career in a creative field.

The flip side of this is that I am a high-functioning anxiety-ridden person, something I have since learned is common among migrants, thanks to the self-imposed pressure to succeed in a non-typical career path. Through our schooling years, my mother felt her own pressures as a parent to prove that she had done the right thing by moving us away from friends, family and an extremely rigid but successful education system in Malaysia. Eventually, as my mother began to settle, so did her pressures, however once you are raised with that level of stress and determination to prove your worth, it is nearly impossible to shake. The thing is, as you get older, the pressures from family might become easier to deal with, but you begin to see how you are compared to other migrants and people of colour.

It starts to feel like people begin to keep score. How successful are you? Have you assimilated enough? Are you able to not rock the boat?

Through my creative work, I have been lucky enough to explore my experiences of loss, longing and identity while finding my feet between Australia and Malaysia, but that does not mean the pressures I have been raised with ever go away.

Writing and making art about your life not only airs all the dirty laundry so publicly, it also challenges a swathe of cultural norms.

Writing and making art about your life not only airs all the dirty laundry so publicly, it also challenges a swathe of cultural norms. Internally within our communities and externally through more detached friends and family, people assume that you will go into work “respectable” enough to support and represent your community respectfully.You will become the hard-working migrant worthy of battling negative stereotypes, support an entire community and uphold a thriving career both your family and the most conservative people in Australia will deem worthy.

Each day, I am determined to be the best at everything I put my name to because I am not just one person, I, like many people of migrant backgrounds, am the sum of a whole family and every experience we have ever had. And with each step I take on the less travelled path, I feel the force of their collective strength and brilliance behind me.

Haneen Mahmood Martin is a Malaysian-Australian artist, curator, activist and producer based in the Northern Territory. Follow her on Twitter @puterihaneen

This article was edited by Candice Chung, and is part of a series by SBS Life supporting the work of emerging young Asian-Australian writers. Want to be involved? Get in touch with Candice on Twitter @candicechung_.