Oora- aira- eeree- sassa- hahaa. The first five letters of the Punjabi alphabet and the only five I remember confidently from my Punjabi school days. How easily they roll off my tongue, a familiarity to an aspect of my heritage I can barely remember. Every other evening, I sit with my mum and read stories written in Punjabi from a children’s book. I squint and struggle to make out all the words and accents but Mum patiently guides me along. When my tongue gets tied, when I know the next word but just can’t say it, when I forget what sound the little squiggly line at the top of a word makes, my face scrunches up in frustration. Likewise, when I read a whole sentence without error, it’s like I’ve levelled up in a game. I think of my parents and all the other immigrants who learn English as a second language, not solely for pleasure but to ensure they will be able to survive in their English-dominated adopted homelands. Maybe there would be less animosity and greater acceptance of accents in society if people understood this.

Now that I am 29, my desire to learn Punjabi stems from my personal goal I’ve set of reading a book from every country in the world. It has dawned on me that the majority of books I had been exposed to growing up in Australia were entirely by white authors. I wondered what other stories were out there and started researching books from all over the world. So far, I have discovered many wonderful authors such as Anuk Arudpragasam, Susan Abulhawa and closer to home, Indigenous writer Melissa Lucashenko. I began to wonder what stories and novels my parents had grown up with. It turns out, there isn’t a whole lot of Punjabi literature that has been translated to English so I decided to learn the language instead with the goal of reading a whole novel in Punjabi.

It has dawned on me that the majority of books I had been exposed to growing up in Australia were entirely by white authors. I wondered what other stories were out there and started researching books from all over the world.

To my surprise, my Punjabi lessons with my mum have become more than just learning how to read words; they have become a means to connect to my culture in a new way and deepened my understanding of where my parents come from and how they see the world. My mum shares stories about her life in the pind, like how all the kids used to look forward to festivals such as Lohri with its big bonfires and Vaisakhi because it meant lots of food and sweets they didn’t usually get. She shares the songs she grew up with and answers my many questions on how half of our wedding traditions such as jago came about. There is so much to the Punjabi culture I still have to learn. Language and culture are closely linked. There are many words in all different languages that have no direct English translation and words that can only be understood in certain contexts. There are stories that can only be told in certain languages, whose beauty would be lost if it was written in any other way. English is the most dominant language in the world and I think sometimes we forget there are so many worlds beyond it. I remember a friend who had read Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s work in both English and Spanish and described how the experience of the novel was different in each language. Similarly, when my parents translate Punjabi phrases for me, they never seem to sound as right in English.

Language and culture are closely linked. There are many words in all different languages that have no direct English translation and words that can only be understood in certain contexts. There are stories that can only be told in certain languages, whose beauty would be lost if it was written in any other way. English is the most dominant language in the world and I think sometimes we forget there are so many worlds beyond it. I remember a friend who had read Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s work in both English and Spanish and described how the experience of the novel was different in each language. Similarly, when my parents translate Punjabi phrases for me, they never seem to sound as right in English.

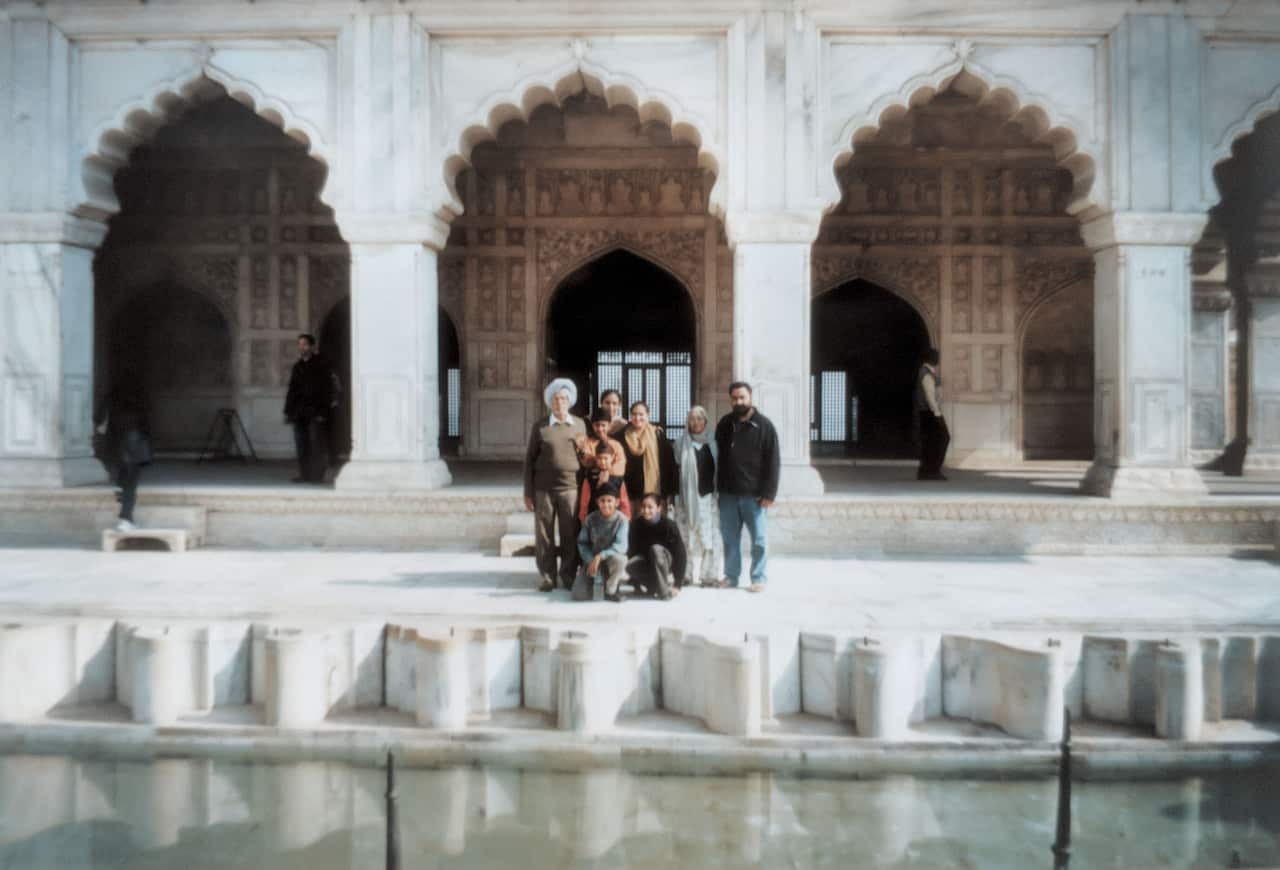

Source: Supplied

Between 1950-2010, 230 languages went extinct and every two weeks a language dies with its last speaker

According to between 1950-2010, 230 languages went extinct and every two weeks a language dies with its last speaker, with 50-90 per cent predicted to disappear by the next century. We don’t just lose a language, we lose art, literature, music and the diversity of the world. Language is powerful and it is what essentially makes humans, human. Punjabi is currently the 10th most spoken language in the world and one of the fastest growing and is now offered as a HSC subject. There are Punjabi classes offered at the Gurdwara on weekends and it is encouraging to see such passion in the community to keep the language alive.

Learning the language of my parents not only ensures the language survives, but also helps me maintain a connection to my culture that I can pass on to the next generation. It was daunting and hard to start at first (mainly due to the trauma of overseas visits to the homeland where relatives snickered at the way I spoke) but has been rewarding nonetheless. I attended Punjabi school when I was younger but would often leave class early because I found it so boring and pointless. Coming back to Punjabi as an adult has been a much richer experience for me because I now understand the importance and value of it. I treasure the time I get to spend with my mum through these lessons and understanding her world a little better. I am nowhere near ready to read a novel in Punjabi yet but I am determined to get there; one letter, one sentence, one story at a time.

This article has been published in partnership with Sweatshop Western Sydney Literacy Movement.