When my daughter was a child, I’d lie in bed with her at night, reading stories and talking before she grew sleepy and I tiptoed out. Now that she’s an adolescent and an independent reader, the ritual of talking remains. As we stare at the lamp-lit ceiling, she tells me her worries and her issues.

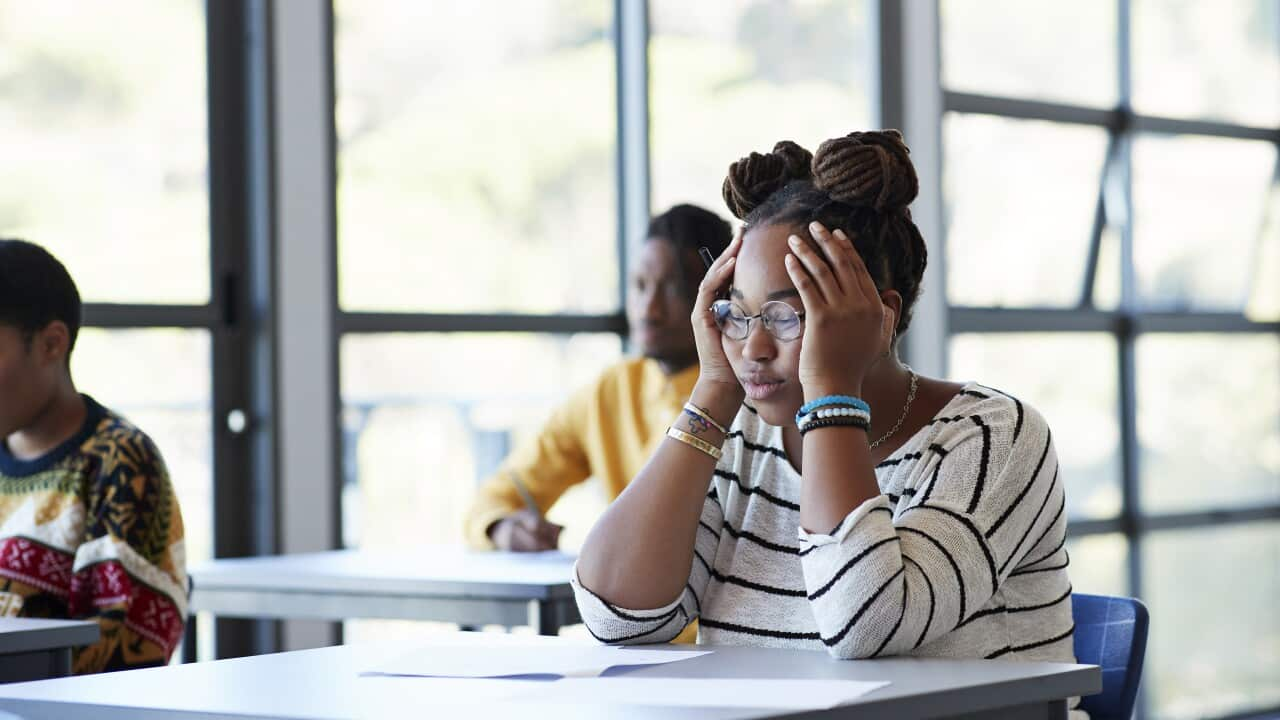

“I’m going to fail maths,” she groans.

“You’ll be fine,” I say. She always grizzles that she’ll fail and always gets high grades. “Anyway, you’re doing better than me, I only got Es in maths.”

“This year I want to make more friends,” she says. She has had two best friends since Year 7 and they have been a tight-knit threesome.

“You’re doing better than me,” I say, half-jokingly. “I only had one best friend in high school.”

“Mum, just because my problems aren’t like the problems you had, it doesn’t mean they’re not problems.” She turns her back to me and shouts goodnight.

Growing up, my childhood was chaotic and constantly changing. My daughter had listened to my many tales of woe: from being taken into foster care when my mother was in hospital for , to the numerous primary schools I attended, and the subsequent impact on my academic achievement.

Chastened, I apologise. She grudgingly accepts.

As I reflect on our conversation, I remember the times when my mother competed with me in what I’d call the “hardship olympics”. Back then, when I grizzled about going to school, she would tell me I was lucky to go at all, since she only finished grade five. Or that my half-hour walk to school was nothing compared to the three-kilometre path she had to trudge through to get to class in deep snow. Or how, as an adult, I shouldn’t complain about being tired after a full day’s work as a teacher – given she did actual, backbreaking work on the factory floor.

I used to feel like I had no right to complain. After all, my childhood was still better than my mother’s. And while I lived with constant uncertainty of when her illness would strike, I still never went hungry or wanted for the basics such as clothes or medicine, like she did in her impoverished childhood in Bosnia.

The times my mother competed with me in the “hardship olympics”... left me feeling like I had no right to be unhappy about anything – if I was, I’d be disrespecting her sacrifices

My mother had sacrificed her opportunities, her connection with her family and her own mental health to migrate to Australia. Being born on this soil gave me more opportunities and a better standard of life than she had growing up; or that I would’ve had if I were born in the land of her birth. While I have no doubt that her intention was to help me appreciate the privileges of my life, it left me feeling like I had no right to be unhappy about anything – because if I was, I would be disrespecting her sacrifices.

Now, years later, I am stunned to catch myself doing a similar thing to my daughter. In attempting to demonstrate that she has a better life than me, and therefore everything will turn out okay, I am diminishing her problems and not giving her the opportunity to process her unhappiness.

I once saw a scene in the TV series Ginny & Georgia and was struck by the way 15-year-old Ginny says she could spot young kids who were happy and loved. How she promised herself that would be her own daughter one day. And I feel the same. I’m so happy that my daughter doesn’t have the fraught childhood that I did, and therefore doesn’t have to fight to overcome the trauma and the hollowness it leaves behind.

Those of us who have survived hefty setbacks are often spoken about as resilient... But that’s because we hide the broken edges from others

Those of us who have survived hefty setbacks are often spoken about as resilient, as people who have a special power to “keep going”. But that’s because we hide the broken edges from others. What we privately wonder is who we could’ve been if we didn’t have to overcome the adversity of our trauma.

My daughter is testament that there can be a better life. I have to stop minimising her problems. They are still struggles for her. I have to opt out of the hardship olympics and be her soft place to land, free of judgement or ridicule.

The next time we lie down together, she grizzles about dreading going to school. I hold back my knee-jerk response to tell her that she dreads school because her home-life is so good. Instead, I agree that it’s hard at the beginning of the term because everything is new again: the classes, the teachers, the classmates. And it’s natural to feel apprehension when you’re out of your comfort zone.

“You just watch, in a few weeks, when it all becomes routine, it won’t be so hard.” She snuggles tighter against me and I kiss her on the head, relieved that I have found the grace to dignify her problems and be there for her.

is an award-winning author of Sabiha’s Dilemma, the first two books in her #OwnVoices young adult Sassy Saints series. Her books are published in ebook, paperback, hardcover, large print, dyslexic font and audiobook.

Related reading

I was blindsided by the demands of motherhood

]