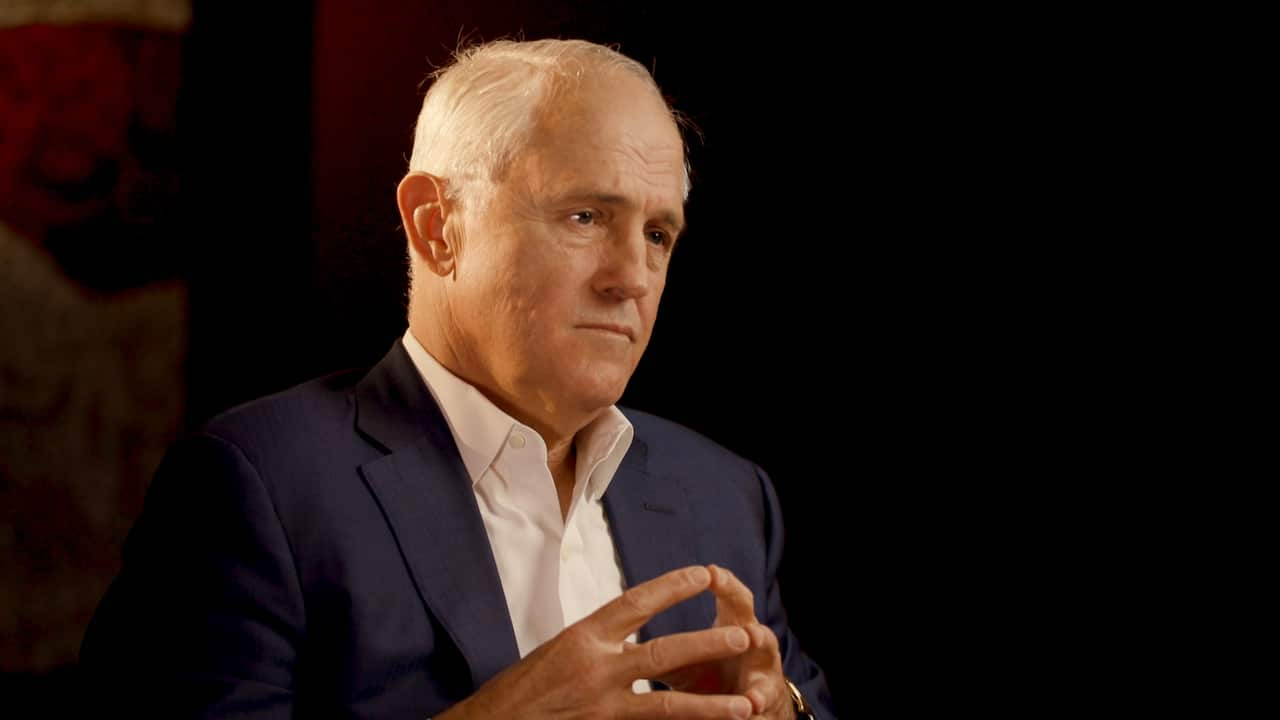

In a revealing interview with Living Black, former Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull sets out the reasons why he did not support an Indigenous Voice to Parliament.

Mr Turnbull believes “that all Australians are equal” and “that we all have equal rights under the law”. In addition to this he also believes that “everyone has a right to have a seat at the table” in determining matters that affect them.

I’m sure that if you had to express these views to the hundreds of families who have had loved ones die in custody and to those who are exercising their democratic rights to protest against black deaths in custody and the racial inequality faced by Indigenous Australians in this country, they would put up some very fierce arguments.

Indigenous Australians have been fighting for decades for a seat at the table and a right to be a part of making decisions that affect them.

That opportunity was almost there. However, the axe fell on the Voice to Parliament concept when former Prime Minister Malcom Turnbull and his government rejected it in October 2017.

It’s well documented that three years ago, the Referendum Council handed its Final Report to the Turnbull Government. Recommending a Referendum be put to the Australian people, to enshrine a First Nations Voice to Parliament in the Constitution, along with setting up a Makarrata Commission and to have a truth-telling process.

“Now, I don’t think that’s a good idea, bluntly. I believe that all of our national institutions should be open to all Australians, regardless of their race, whether they’ve descended from Aboriginal people who’ve lived here for 60,000 years or whether they just got their citizenship yesterday.”

These recommendations came from almost 2 years of consultations with Indigenous Australians held around the country culminating in the Uluru Convention in May 2017. Here a consensus of First Nations people agreed on these key elements which formed the Uluru Statement from the Heart.

As Mr Turnbull understood the proposition “it should be a national assembly council elected only by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to which only Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people could be members. And that Parliament have an obligation to consult with it, with respect to laws relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.”

“Now, I don’t think that’s a good idea, bluntly. I believe that all of our national institutions should be open to all Australians, regardless of their race, whether they’ve descended from Aboriginal people who’ve lived here for 60,000 years or whether they just got their citizenship yesterday.” “And I did not think that was a good idea to put in the constitution. I might say, I also believed, and I say this with the experience of someone who knows what it's like to lose a constitutional referendum, I don't think it has any prospect of being successful in a referendum. It's literally doomed because it would be opposed strongly. And the lesson from constitutional referenda is that unless you get virtually everyone to agree with it, you can't get it up.”

“And I did not think that was a good idea to put in the constitution. I might say, I also believed, and I say this with the experience of someone who knows what it's like to lose a constitutional referendum, I don't think it has any prospect of being successful in a referendum. It's literally doomed because it would be opposed strongly. And the lesson from constitutional referenda is that unless you get virtually everyone to agree with it, you can't get it up.”

Ex Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull talks to Karla Grant on Living Black. Source: NITV

When I asked Mr Turnbull if the Referendum Council had a mandate to come forward with a Voice to Parliament his answer was simple.

“Well, honestly, it certainly wasn’t what I was expecting.”

When the Referendum Council presented its Final Report to Mr Turnbull and then Opposition Leader Bill Shorten in July 2017, the former Prime Minister said it was “a very big new idea”, that was “very short on detail”.

While Mr Turnbull said that he wasn’t expecting what was presented to him and claimed it was a big new idea, he in fact had prior knowledge that this was likely to be the Referendum Council’s recommendation.

Well, it's up to you as to what you recommend. But for my par, I don't think it's a good idea inherently for the reasons I've described. And secondly, I don't think it's got any prospect of getting up at a referendum.

I quizzed Mr Turnbull on an incident with Noel Pearson that he recounted in his recently published memoirs.

“We had a meeting in November in 2016. And that was when Noel and others on the Referendum Council made it clear that that was what they were supporting. And they thought the council may well recommend that. They canvassed that and we discussed it. And I said, "Well, it's up to you as to what you recommend. But for my par, I don't think it's a good idea inherently for the reasons I've described. And secondly, I don't think it's got any prospect of getting up at a referendum."

Mr Turnbull’s knowledge of the idea of a Voice to Parliament goes back even further than 2016.

Noel Pearson and his legal advisor, Shireen Morris, said they had briefed him about this proposal in June 2015 before he became Prime Minister.

Mr Turnbull said he couldn’t recall the 2015 briefing by Noel Pearson and Shireen Morris.

It’s also known that before the Referendum Council set off around the country to consult with First Nations people in 2016-17, they had written to both Malcolm Turnbull and Bill Shorten to get sign-off on taking to the people the concept of an Indigenous Voice to Parliament along with agreement making as well as the recommendations made by the Expert Panel on Constitutional Recognition.

As former Referendum Council member, Megan Davis told me in a recent interview, both Mr Turnbull and Mr Shorten signed-off on that process.

When asked whether he was being wedged by conservatives in his party to reject the voice Mr Turnbull replied “No, not at all. No not at all. My view on the proposal of having this Indigenous only assembly embedded in the Constitution is a thoroughly principled one.”

“He was certainly seeking to destabilize my leadership constantly. And generally, in not just behind the scenes, but in open view. I mean, he and others were running a right-wing insurgency against my government for its whole term, you know?"

I also asked whether he felt that Tony Abbott was working behind the scenes using the argument against the voice to destabilize his leadership?

“He was certainly seeking to destabilize my leadership constantly. And generally, in not just behind the scenes, but in open view. I mean, he and others were running a right-wing insurgency against my government for its whole term, you know? That was one of the challenges I faced. But on this issue, the view that I have about it, both about the substance of the proposal and its electability or constitutional electability are ones that are quite sincerely held”.

While former Opposition Leader Bill Shorten doubts whether Mr Turnbull was ever interested in constitutional recognition of First Australians, Mr Turnbull is quick to set the record straight. “No, I was very interested in it. In fact, it was an issue at the time of the Republican Referendum back in ’99. And we collaborated and supported a change to the preamble to acknowledge Aboriginal people and the entirety of our human history. But sadly, that was defeated at the same time as the Republican Referendum.”

“No, I was very interested in it. In fact, it was an issue at the time of the Republican Referendum back in ’99. And we collaborated and supported a change to the preamble to acknowledge Aboriginal people and the entirety of our human history. But sadly, that was defeated at the same time as the Republican Referendum.”

Ex Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull talks to Karla Grant on Living Black. Source: NITV

The former Prime Minister stands firm on his reasons for not supporting the Voice to Parliament.

He also makes no apologies unlike his former colleague Barnaby Joyce that the voice could have become a Third Chamber of the Parliament.

“I agree. I actually used that term myself. I mean, I think it would evolve into that.”

“Look, I don’t want to be critical of the Referendum Council. But basically, what they presented was a column of smoke and you couldn’t grapple with it.”

His concern was that if there was an Indigenous national assembly or council embedded in the Constitution, Parliament would have to consult with it on any matter relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, which would include most matters such as laws on tax, health and education. If the assembly or council wanted more time to consider these matters, it could hold up legislation going through the Parliament and in turn take matters to the High Court.

“Look, I don’t want to be critical of the Referendum Council. But basically, what they presented was a column of smoke and you couldn’t grapple with it.”

“If you wanted to produce a proposal of this kind, it should have been a detailed bit of drafting.”

“So, if you want to change the Constitution, you’ve got to be really clear about what it all involves because one thing Australians know is that once you change the Constitution, it’s very hard to change it back.”

Mr Turnbull believes First Nations people can have a voice without necessarily changing the Constitution.

“There is an opportunity to do more in the area of representation, representative bodies and you can do that without constitutional change. So, that makes things a lot easier if you do that, a lot easier to achieve.”

Let’s hope that Indigenous Australians do get a voice whether it’s to Parliament or Government, something is desperately needed to effect major change in this country.