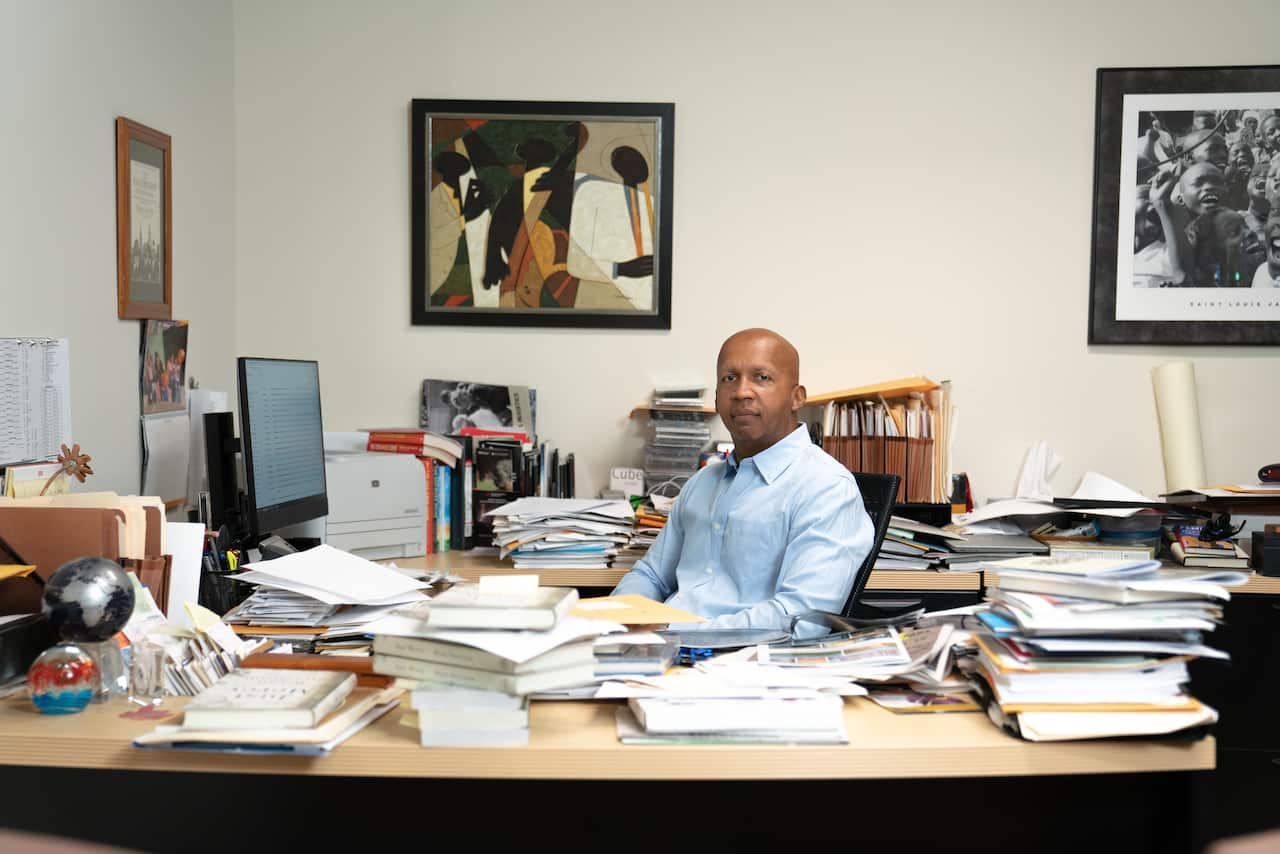

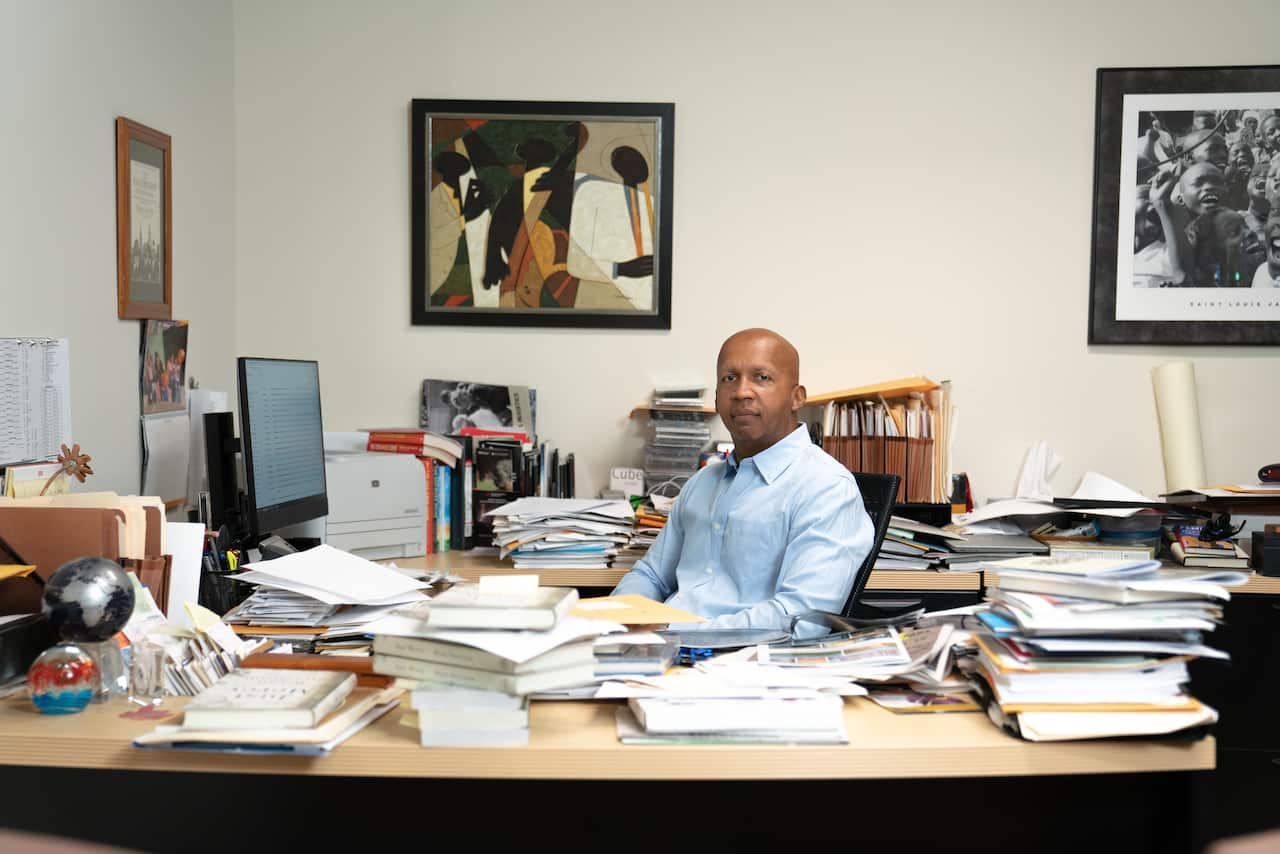

The name Bryan Stevenson may not be well-known to many, but he is what you would call a real-life hero.

Stevenson is a remarkable man who has devoted his life to fighting against racial inequality in the American criminal justice system.

He defends the rights of the poor, the marginalised, those who have been wrongly convicted and the condemned He has saved the lives of around one hundred and sixty people on death row.

Over thirty years ago he set up the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI) in Montgomery, Alabama. The EJI is an organisation devoted to ending the mass incarceration and excessive punishment of African American people in the United States.

In 2019, I had the great privilege of travelling to Alabama to interview Bryan Stevenson about his extraordinary life and career and to see first hand the incredible work of the EJI.

I also spoke to Stevenson about the film “Just Mercy”, the powerful feature film released earlier this year in Australia, which is based on his memoir of the same name.

Since the movie was released in the US last year, Stevenson has found himself in the spotlight and receiving widespread recognition for his work in saving the lives of African American men from the death penalty.

But it’s been a long road to get to this point in his life. Born towards the end of the Jim Crow era, the laws that legalised racial segregation in the US, Stevenson grew up in a poor segregated community in Milton, Delaware.

Born towards the end of the Jim Crow era, the laws that legalised racial segregation in the US, Stevenson grew up in a poor segregated community in Milton, Delaware.

The name Bryan Stevenson may not be well-known to many, but he is what you would call a real-life hero. Source: Paper Monday

He remembers starting his education at a coloured school as black kids were not allowed to attend public schools and there were no high schools for black kids in his county.

Stevenson said it was challenging as his family were marginalised and excluded and were not allowed to go to certain places. He said it was humiliating to live in a society where you are judged as not being worthy.

Eventually the laws changed, the transition was by no means an easy one but he was able to attend a public high school and college to get an education.

Stevenson attended college in Pennsylvania and went to law school at Harvard University, he eventually realised that human rights and social justice was the path he wanted to pursue.

As part of his law course he had to spend a month with a human rights organisation which provided legal services to people on death row in Georgia. This is when he first met condemned prisoners needing legal assistance. It was a life changing experience.

After graduating from Harvard, Stevenson moved to Montgomery Alabama, where he established the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI) in 1989. He was motivated to set up the EJI in Alabama because it was a state that did not have a public defender system and people were not getting the legal assistance they needed.

He was motivated to set up the EJI in Alabama because it was a state that did not have a public defender system and people were not getting the legal assistance they needed.

Bryan Stevenson Source: Supplied

Stevenson could see flaws in the criminal justice system and the unfair treatment of the accused. His view is that the system treats you better if you are rich and guilty than if you’re poor and innocent.

He told me it’s a challenge to meet the great legal needs that they have. He said in 1972 the prison population was approximately 200,000, jumping to 2.2 million in 2019. And while $80 billion has been spent on prisons, millions of dollars have been spent on police and prosecutors, while very little money has gone into building infrastructure to meet the needs of people who need lawyers.

Stevenson says as a result there are thousands of people in prisons who are innocent of crimes for which they have been convicted and tens of thousands who have been unfairly and wrongly sentenced. And this is why EJI exists.

Walter McMillian Case

His first high profile death row case was that of Walter McMillian who was wrongly convicted of murder in 1986. He said after reading all the records for the case, it was apparent that Mr. McMillian was innocent but it was a struggle to overturn the conviction. He said there is an unwillingness in the justice system to acknowledge error or admit they made a mistake.

He said there is an unwillingness in the justice system to acknowledge error or admit they made a mistake.

Walter McMillian and Bryan Stevenson Source: Supplied

Stevenson was also faced with another hurdle. He said there is a presumption of danger and guilt that gets assigned to black and brown people in the US. He said they are still dealing with the legacy of slavery, of native genocide, which has created a narrative of racial difference and the ideology of white supremacy. He said that legacy creates burdens on people of colour where they must prove their innocence. They have to overcome that presumption.

He said that’s how Walter McMillian ended up on death row for a crime he didn’t commit. He was presumed guilty, he was presumed dangerous and that made it very easy for the state to put him in that very difficult situation and very hard for Stevenson and his team to win his freedom.

In 1988, Stevenson met McMillian and took on the case to appeal his conviction and death sentence. Stevenson and his team discovered evidence that proved Mr. McMillian was innocent.

After spending six years on death row, the conviction was overturned by the Alabama Court of Criminal Appeals in 1993 and prosecutors agreed the case had been mishandled. Mr. McMillan was a free man.

Just as Indigenous Australians are being incarcerated at alarmingly high rates, so are our black brothers and sisters in the United States.

But what is the solution? What changes need to be made to the justice system to ensure African Americans are not incarcerated at such high rates?

Stevenson says they must stop putting people in prison for things that are not crimes, such as drug addiction and drug dependency. He said they need the healthcare system to respond to that and to not throw people in jail for something that is a health problem. He said they also need to create a more robust system to help those who can’t afford legal representation so that they have the tools to defend themselves.

He said they also need to create a more robust system to help those who can’t afford legal representation so that they have the tools to defend themselves.

Bryan Stevenson with Colleagues Source: Supplied

Stevenson believes police and prosecutors need to be held accountable for misconduct and abuse and that immunity laws need to be revisited.

He also says that more needs to be done in terms of rehabilitation of people in prisons. He says they are warehoused, abused then sent back out into the community where they are primed to re-offend and then they are excluded in society and face barriers for employment.

But Stevenson says there is a larger challenge facing people of colour in the US. And that challenge is the broader history of racial injustice and changing the narrative in the states.

By changing the narrative Stevenson says there needs to be more talk about the history of native genocide, slavery, segregation and to find a way to create a future that is less burdened by this history. It is almost like this history has been swept under the carpet much like the black history of Australia.

National Museum for Peace and Justice

One-way Stevenson has tackled this is by setting up the Legacy Museum and the National Museum for Peace and Justice in Alabama so that Americans can acknowledge and understand their history just as we are doing in Australia through truth-telling. The National Memorial honours the thousands of African Americans who were battered, bloodied and lynched and burned and drowned during the period between 1877 and 1950.

The National Memorial honours the thousands of African Americans who were battered, bloodied and lynched and burned and drowned during the period between 1877 and 1950.

National Memorial For Peace And Justice Source: Supplied

Visiting both memorials when I was in Montgomery was a truly emotional experience. I remember feeling physically ill reading the stories of those who were murdered just for walking alongside a white person. Or for simply drinking water out of the same tap as a white person.

Stevenson is right when he says memorials like these are needed all over the world, like Australia, Canada and America where injustices have taken place. He says it’s necessary for us to lift up the truth about our history because it’s the only way we can then understand the kind of repair, the kind of remedy that’s going to be needed to get to a healthier place. It’s what we call the healing process.

Despite all the challenges faced, Stevenson remains hopeful about his work in helping the wrongly convicted, the condemned, the unfairly sentenced and creating an era of truth and justice that is so desperately needed.

Stevenson said, “It's not a pie in the sky hope, it's not a preference for optimism over pessimism. It's just an orientation of the spirit. I think we have to be willing to believe things we haven't seen. That's our superpower. I had to believe I could be a lawyer even though I'd never met a lawyer who looked like me. We had to believe that we could create an institution that could help people on death row, even though we hadn't seen that happen. We had to believe we could build a museum and a memorial in the heart of a pretty hostile space when it comes to racial justice. And yet we've achieved all of those things. And so, I think hopelessness is the enemy of justice. I think injustice prevails where hopelessness persists. And so, hope is our requirement, it's our superpower.”