WARNING: This article contains images and names of deceased people.

You've seen his face countless of times, held it in your hands, kept it tucked away in your wallet or deep in your pockets.

The portrait of Gwoja Tjungurrayi has graced the $2 coin since they replaced banknotes in 1988.

But his story began years before.

The Coniston Massacre

A Warlpiri-Anmatyerre loreman from the Northern Territory, Tjungurrayi, was believed to be born around 1895 in the Tanami Desert, north-west of Alice Springs.

He was a survivor of the Coniston Massacre that took place over many months in 1928.

Earlier that same year, the body of a white dingo trapper, Fred Brooks was murdered and his body was found in a shallow grave at Coniston Station.

Alongside his body laid traditional weapons.

Two Warlpiri men were arrested for the murder of Brooks and held in Darwin before being found not guilty. Eye-witness accounts suggested Kamalyarrpa Japanangka, also known as ‘Bullfrog’ was responsible.

It's believed that Brooks violated Warlpiri marriage law, with secondary accounts suggesting he sexually assaulted one of Bullfrog's wives.

When his body was found, a reprisal party was formed, led by Sergeant William Murray who had recently returned from serving in the first World War.

The former soldier led a small group of police and civilians to Coniston Station. From August until October, the men killed 60 Aboriginal men, women and children.

"When I was a little girl I saw my people shot - all because they lived off this country and because they were Aborigines," recalled one survivor.

"Some of our parents and grandparents hid us in caves. During the day we'd go without water and hide from the whitefellas. At night our parents would sneak out to the soakages to get water for us to drink."

Anthropologist, Petronella Vaarzon-Morel, collected the.

The women repeatedly told her stories of the fear that stayed in their families and communities years after the killings.

"People had to hide well after the Coniston killings. They were in terror of these people coming onto their land, killing them," she told SBS.

"And some of the women who were very young at the time have told me how, a number of years afterwards, they hid away from the white men in these areas that had bullets.

"They would cover themselves up with sand during the day when their mothers went out hunting, afraid in case whitefellas came.

"And, you know, immediately afterwards, they wouldn't make fires to cook food, they had to be very careful. They lived in ... in terror that ... that this would happen again."

Coniston Massacre memorial which stands on the lands where more than 60 Aboriginal people were killed. Source: AAP

The first states he was taken prisoner by Sergeant Murray, before escaping with his family to the Arltunga region of Alice Springs.

The second, says he was seen ‘worm[ing] his way out from among the dead and dying’ at Yurrkuru to ‘narrowly escape death from a hail of rifle fire poured at him by whites’.

A chance encounter

Less than a decade later, a young tourism executive from Melbourne, Roy Dunstan, was driving through desert country, east of Alice Springs when he spotted two Aboriginal men walking.

One, was Tjungurrayi.

Dunstan was collating photographs for a new tourism magazine Walkabout and, upon meeting the two men who were walking to a large ceremonial gathering, took a series of staged photos of Tjungurrayi.

In September 1936, a year after the photos were taken, Tjungurrayi was featured on the front cover of Walkabout.

He was featured again on the cover of the September edition in 1950, with the description reading "Australian Aboriginal".

Gwoja Tjungurrayi on the cover of the Australian Geographical Walkabout Magazine 1936. Credit: Wikimedia Commons

At Napperby he met his wife, Long Rose Nangala.

From there, with his family to care for, Tjungurrayi began working as a stockman and station hand. A career that lasted him 20 years.

It's also believed at some time, he was a boomerang salesman.

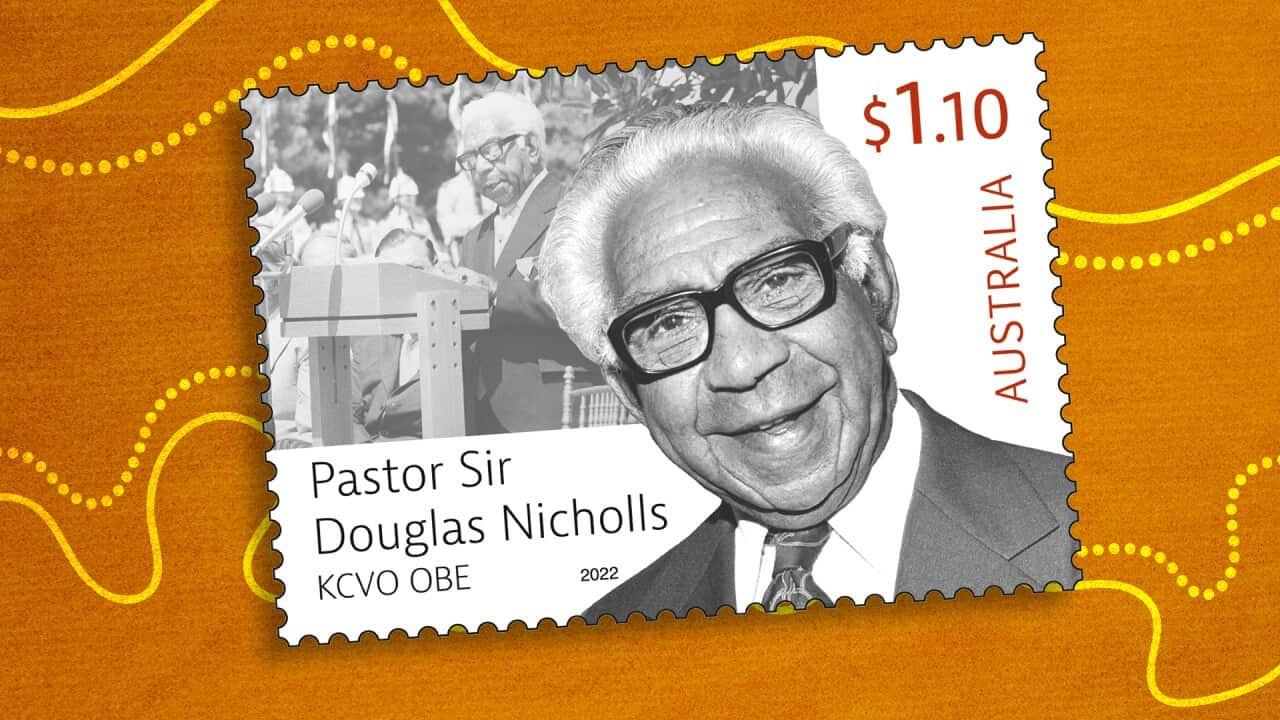

First Australian on a stamp

The image of Gwoja Tjungurrayi took the country by storm with him becoming the 'icon' for Aboriginality in colonial Australia.

In 1950 to 1966, over 99 million stamps bearing his image were sold.

The stamp cemented his status as the first person, other members of the royal family, to feature on an Australian stamp.

With his face branding letters across the nation and the world, Gwoja Tjungurrayi quickly became known as 'One Pound Jimmy'.

Whilst the nickname seems endearing, some believe it's offensive.

Gwoja Tjungurrayi also known as One Pound Jimmy on an Australian stamp in the 1950s. Credit: Wikimedia Commons

But in 2021, research revealed that Gwoja Tjungurrayi was featured on a 1938 stamp celebrating the Geelong Centenary.

The stamp, however, had no decimal mark so was never formally used. Instead, it was a collector's item.

The $2 coin and beyond

In 1988, $1 and $2 banknotes were taken out of circulation and coins were introduced.

On June 20 of that year, the Royal Australian Mint released the $2 featuring the portrait Tjungurrayi.

The coin's design, inspired by a portrait of Tjungurrayi by artist Ainslie Roberts is said to represent "an archetype" of an Aboriginal Elder.

Unfortunately, Tjungurrayi never got to see his image on coin, passing away almost two decades before its release - in March 1965,

Two dollar Australian coins featuring an image based on a depiction of Gwoja Tjungurrayi. Source: iStockphoto / CreativaImages/Getty Images/iStockphoto

Formerly named Stuart, after explorer John McDouall Stuart, the electorate is now named Gwoja, in honour of Tjungurrayi.

Tjungurrayi's story lives on in more than stamps, coins and electorates, but in his children.

One of his sons, Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri built a career as an esteemed Western Desert artist.

Another son, Tim Leura Tjapaltjarri created a painting in 1997 titled 'Ancestor Dreaming' which was featured on an Australian Post stamp series celebrating the people and art of the Western Desert.