Content warning: this article discusses themes that may be distressing to some readers, including violence and sexual assault.

It's telling that one of the few Aboriginal names that garners even vague recognition from wider Australian society is associated with Indigenous people's extinction.

In her own lifetime, Truganini was said to be the 'last Tasmanian Aborigine'. The many palawa people living in lutruwita today are an obvious rebuke to this fallacy.

There's another untruth that is often told about Truganini's life: that it was 'tragic'.

Offensively reductive, it is also inaccurate. Tragic things happened to this Nuennonne woman, but she was not tragic: a woman of her skill, beauty, intelligence and grit couldn't be.

She was powerful.

Truganini repeatedly displayed it in the midst of one of the world's darkest and most gruesome chapters, the subject of a new SBS/NITV documentary series The Australian Wars.

It's time the power of her story is reclaimed.

Daughter of time

Truganini was a famous beauty. She can be seen here again wearing the mariner shells, a constant presence through her life.

She is believed to have been born around 1812. Though the British had already expanded their invasion of the sovereign Aboriginal nations down to lutruwita (Tasmania) in 1803, the delayed onset of colonisation in those lands meant Truganini thrived within a cultural childhood.

Her father was Mangana, a leader amongst his people, the south-eastern dwelling Nuennonne of Lunawanna-alonnah (Bruny Island).

She was a keen hunter-gatherer: an excellent swimmer, she loved harvesting mussels, oysters and scallops, diving for crayfish, hunting muttonbirds and collecting mariner shells, used to create the magnificent traditional necklaces of that region, which she proudly wore.

Truganini's people would travel seasonally, ritually paddling in bark canoes to Leillateah (Recherche Bay) to meet with the Needwondee and Ninine people, sometimes trekking overland to the Country of those tribes in the west.

Named for the grey saltbush truganina, the Nuennonne woman was to display similar qualities to that tough native, which can withstand drought, wind and poor conditions; she was to weather her own storms, and lived a long life.

Negotiating the apocalypse

The Rufus River Massacre, one of the atrocities of The Black War, which blighted Truganini's youth.

The horrors visited upon the palawa were gruesome, the Aboriginal attacks of retribution fierce.

The ever-worsening death toll saw the Van Diemen's Land governor, Lieutenant George Arthur, declare martial law in 1828, when Truganini was 15. It essentially condoned the murder of Aboriginal people.

By the following year, Truganini had experienced devastating losses: her mother had been killed, her uncle shot, her sister abducted and her fiance murdered.

It makes her own story of survival all the more astounding. While First Nations people across the continent were losing Country, culture and life, Truganini negotiated a narrow path of autonomy across her six decades.

As historian Cassandra Pybus notes, she repeatedly achieved for herself, “within the extremely limited range of options available for her at various stages in her life, the best possible outcome.”

Despite stints in the death camps at Flinders Island and Oyster Bay, where the remnants of the island's Aboriginal population were forced together, it seems she secured relatively regular access to her Country on Lunawanna-alonnah throughout her life (which may have been key to her longevity).

Her beauty, admired by all, white and Black alike, was used to its full extent. Truganini used her beauty, seen as a "", to extract from settlers what she wanted at given times.

She also had an incredible force of will, often bending colonists to satisfy her needs.

Towards the end of her life she lived in comfortable conditions with a white family (again, near her Country). By now famous as the 'last of her kind', colonists would often seek her out for photos, interviews or simply to say they had met her, all to raise their cachet.

Truganini would always negotiate a benefit for herself from these meetings.

A skilled diplomat

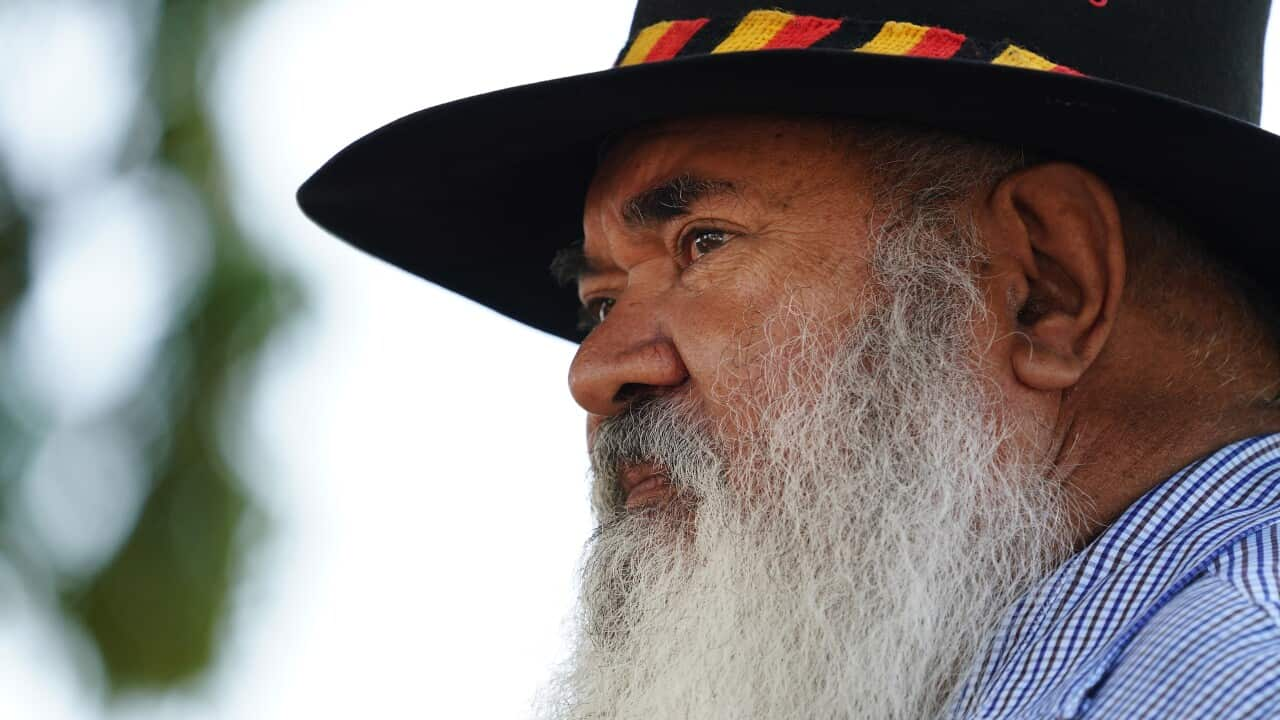

George Robinson, the so-called "Protector of Aborigines" in Van Diemen's Land, would become a significant figure in Truganini's life. He relied on her heavily for his personal successes.

He was appointed Protector of Aborigines (using the usual offensive misnomer) in so-called Van Diemen's Land. He had undertaken a mission to convert Aboriginal people to Christianity.

His goal was to gather the severely diminished Aboriginal populations in one location, Flinders Island, where they could be introduced to the mercy of a western God. He was to be paid handsomely for this project.

Truganini became his cross-country guide and a diplomat to the remote tribes that Robinson was attempting to convert.

While it may seem confusing that she would help a white settler in this pursuit, Truganini was a woman of great pragmatism.

She had seen the devastation wrought by the British, watched their numbers swell ever-more, and witnessed the genocide enacted on palawa Aboriginal people during the Black War, which was ongoing.

A portrait of Truganini by Thomas Bock, around the time she met George Robinson. By this age she experienced the devastations of colonisation.

‘I hoped we would save all my people that were left … it was no use fighting anymore,' she said once.

Her work in negotiating with the various tribes, which all had their own complex political realities, was the work of an incredibly skilled diplomat. In 1835, between 300 and 400 people were shipped to Flinders Island.

Robinson's rationale was gruesome in its simplicity: he hoped that by removing Aboriginal people from their lands that they would more readily convert to Christianity. But the separation of Country and kin was a deadly remedy; just two years later, grief-stricken for the loss of their land, 75 per cent of the Aboriginal inhabitants had died.

Truganini had made a calculation of survival, and pursued her goal with determination and political skill. Responsibility for the devastating end result of a racist project on the part of opportunistic whites does not lie on her shoulders.

Palawa people at the Oyster Cove settlement around the 1850s, with Truganini seated far right.

A bushranger to survive

Robinson took precisely the wrong lesson from Flinders Island. He thought that the settlement was too close to the Aboriginal people's original homes, and that if he removed them to the mainland they would soon forget their culture completely.

In 1839, Truganini and 14 palawa accompanied Robinson to the mainland. The missionary intended to establish a similar settlement there, but it seems Truganini had no interest in helping Robinson further.

She refused to speak English, would often abscond, and continued to practice her culture as much as she could. Robinson abandoned her and the others in 1841.

Left in an unfamiliar land and surrounded by a hostile culture, Truganini once again took the matter of her survival into her own hands.

With two men, Peevay and Maulboyheener (her husband), and two women, Plorenernoopner and Maytepueminer, Truganini became a guerrilla warrior.

Some of Truganini's companions during a brief guerrilla campaign. Maulboyheener and Tunnerminnerwait are honoured as martyrs; they became the first people executed publicly in the state of Victoria.

The Port Phillip Herald wrote in inflammatory terms of the disruptions the Black bushrangers had caused, which, limited to property, did not by any account compare to their own suffering.

Truganini was, predictably, an active part of this crusade. The paper wrote that the "three women... are as well skilled in the use of the firearms they possess as the males".

Truganini (seated left), with William "King Billy" Lanne, her husband, and another woman in 1866.

It took another six weeks before they were captured. The court case that followed was a brief affair with a foregone conclusion: the Aboriginal men tried to explain the shooting, justified in their eyes, but they were sentenced to hang. It became Victoria's first public execution in January of the following year.

Truganini, who had survived the affair with a gunshot wound to the head, returned once more to Flinders Island.

A symbol of resistance

The portrait by Benjamin Law of George Robinson attempting to convince palawa people to give up their culture, signified by the traditional mariner shell necklaces.

Entitled 'The Conciliation', the painting by Benjamin Duterrau depicts George Robinson in his attempt to convince the palawa Aboriginal people to move to Flinders Island.

Robinson stands in the centre, surrounded by several famous First Nations leaders of the time: Woreddy, Mannalargenna, Truganini.

He shakes hands with one, as the agreement to end the resistance, and therefore the Black Wars, is finalised.

There is something unique about the man shaking Robinson's hand: he does not wear the distinctive shell necklace typical of the palawa groups.

Truganini never abandoned her culture. She is seen here in later life still wearing a distinctive mariner shell necklace, such as she had worn since her youth. Source: Woolley/National Library of Australia, o

Thanks to the many photographs, paintings, drawings and sculptures made of Truganini during her life, we know that the Nuenonne woman remained true to her culture until her dying days: she is ever adorned by the pearlescent beauty of that necklace.

It's a symbol that remains to this very day: palawa people continue to make those necklaces, continuing the culture that lived in Truganini, and lives still in the descendants that for too long were said not to exist.

Episode 2 of The Australian Wars airs on Wednesday 28 September at 7.30pm on SBS and NITV, and will be available after broadcast on SBS On Demand.