There's differing positions in our community, and across the country, on what the Voice referendum is truly about.

To get a better idea, let's first discuss what it's not about.

It's not about sovereignty (or ceding it). Nor is it about Bla(c)k advocacy.

It's not about extra chambers of parliament, who MPs represent or endless High Court litigation.

It's not about costs, the finer points of the constitution and it's definitely not about endless rice pudding.

It relates to some of these matters, but none of them are what the referendum is truly about.

Who are we?

I'll speak simply, because I'm a simple bloke. I think most Australians are, even though we like to project that we are a sophisticated and worldly bunch. We like things simply put; it clears the BS.

Firstly, what is a referendum?

There's plenty of technical details that I’ll let the experts and constitutional lawyers explain. But in the Australian context, a referendum is a rare and uncomfortable moment.

Why? Because it’s a moment that makes us ask 'Who are we really? What do we really stand for?'

It makes us nervous because, deep down, we know these real underlying questions of referenda are not something we can hide or run away from.

Nowhere to hide

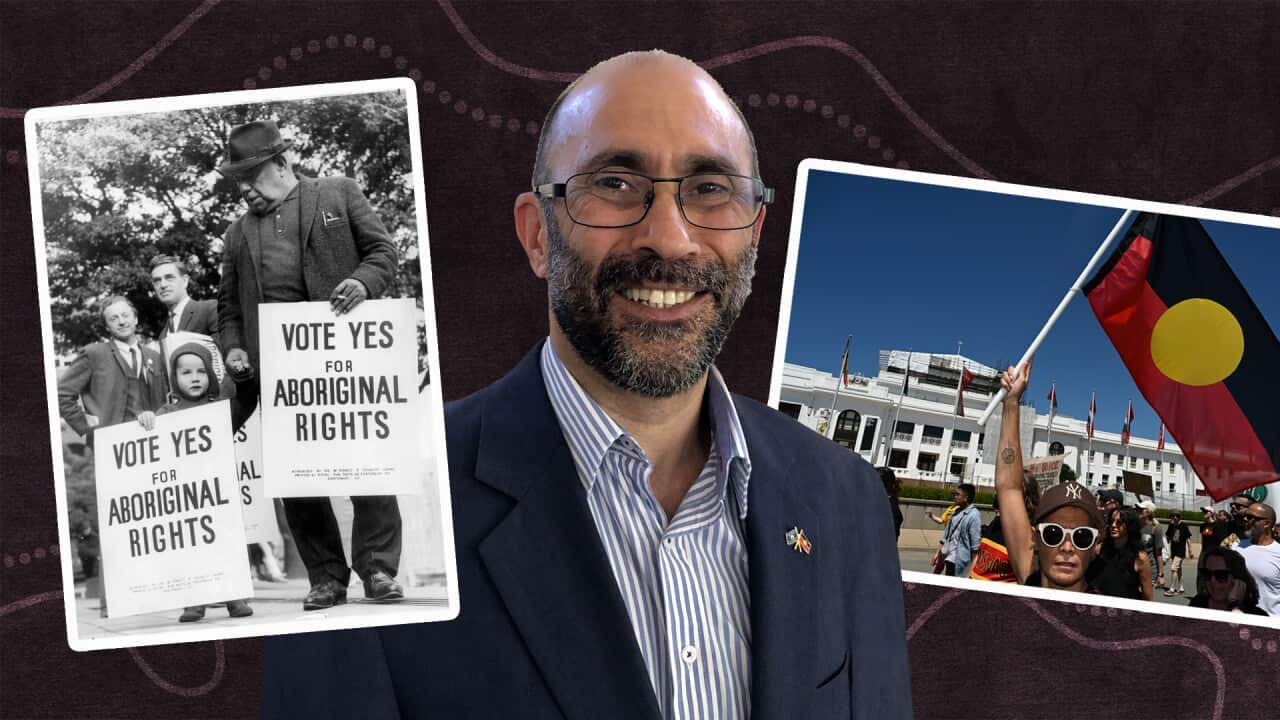

Case in point – the 1967 referendum. An obvious example, but it’s probably the best example of a us being posed a real underlying question about who we are.

On the surface, two questions were posed: whether Aborigines should be counted in the reckoning of the population (the census); and whether the Commonwealth should be able to make laws in relation to Aborigines.

But these weren’t the real questions that Australia had to confront.

Given the well-known and appalling history of Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal relations, Australia had to ask itself the real questions: Do Aboriginal people belong in this country? Do they have a place in the future of this nation?

No qualifiers, no detail, no ‘what if’ implications of what might occur. Nowhere to run, nowhere to hide.

Only Yes or No.

And Australia said Yes.

Prime Minister Anthony Albanese with members of the First Nations Referendum Working Group. Source: AAP / Lukas Coch

The real question

What does this mean for the referendum of 2023?

It means looking beyond all the noise, the leaders, the lawyers, the experts and the commentators and getting to what the ordinary punter wants to know: what is this really about? What is the real underlying question?

Again, we know the surface questions being asked: whether there should be an Aboriginal voice that will advise parliament and government, the details of which parliament will work out.

But the real questions are these: should Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people be able to speak about the things that affect them? Or should we maintain the silence of the blacks?

Tough, uncomfortable, confronting stuff: nowhere to run and nowhere to hide.

Australia, our nation, our country, and each of us as voters, stand naked in front of the mirror of truth, forced to look at our reflection. Some are trying hide under the deceptive cloak of ‘more detail’, or fog it up with the hot breath of litigation, or blind its gaze by throwing a blanket of ‘treaty or nothing’ over it.

But in the end there's just a single question burning in our national and individual souls.

Should Indigenous people be able to speak: yes or no?

Why a Voice at all?

Most Australians know of the appalling life measures for Aboriginal people: shorter lives, poorer health, greater poverty, inequality before the law.

But many Australians don't understand why it is so.

One of the main reasons is that parliaments, governments, ministers and bureaucracies can sometimes make really rubbish decisions, and they do so without taking the time to talk with us. They make decisions about us, without bothering to talk to us.

Would any other part of Australian society tolerate this? Probably (and hopefully) not. They would be outraged and demand the right to be heard.

And yet, this situation has continually occurred when it's Aboriginal people.

Imagine if they did talk with and listen to us though – we may find that government makes better decisions that contribute to improvements in our lives.

Giving voice to Aboriginal dreams

Our peak Aboriginal bodies (NACCHO, SNAICC, NAILS) are fantastic, but they don’t pick up issues or concerns beyond their remit – and nor should they. They have enough to do without also having to be representatives of broadly everything.

This is what the Voice is for: a mechanism to articulate the things that ordinary Aboriginal people want to talk about, beyond gaps and deficits.

It will allow us to talk about everything beautiful about being Aboriginal; what our hopes, dreams, and aspirations are; what we can contribute to the nation and most importantly, what parliament and government can do to support us make all these things a reality.

The most uncomfortable question of all

It would be simpler to legislate the Voice, rather than take it to referendum and enshrine it in the constitution forever.

But a legislated Voice would also be easy to get rid of.

Standing in front of the mirror of truth again, we have to ask ourselves the most difficult and uncomfortable question of all.

Does Australia trust itself, as a people, as a nation and through our parliament and government, not to screw Aboriginal people over again?

I think we all know the shameful answer to that one. All it would take is a desperate PM or an overly excited and ambitious Opposition Leader appealing to the worst traits of the electorate in pursuit of a few shabby votes to throw us to the wolves again.

The constitution can’t guarantee what a Voice looks like or how effective it would be, but by having it named in the document, it means that the parliament and the government will have to deal with us – one way or another.

Ian Hamm works to improve the representation of Aboriginal people on boards and other high-level governance, through strategic action, advocacy and mentoring.

Michelle Obama speaking at the Democratic Party convention in 2012, in support of her husband’s bid for a 2nd term, said of the US presidency, that it doesn’t change who you are, it “reveals who you are”.

Australia is at a clinch point where the outcome of this referendum will not change who we are – it will reveal who we are.

A people, a nation, coming to terms with its past, embracing a better future and bringing a maturity that includes the First Australians – or not.

In the simple mind of a simple bloke - Yes or No?

Yorta Yorta man Ian Hamm is the chair and board member of a number of non-for-profit and public purpose organisations.