In this year, at least 27 women have been murdered by violence.

The rising death toll has spurred rallies across the country and brought the federal cabinet together in emergency talks on violence.

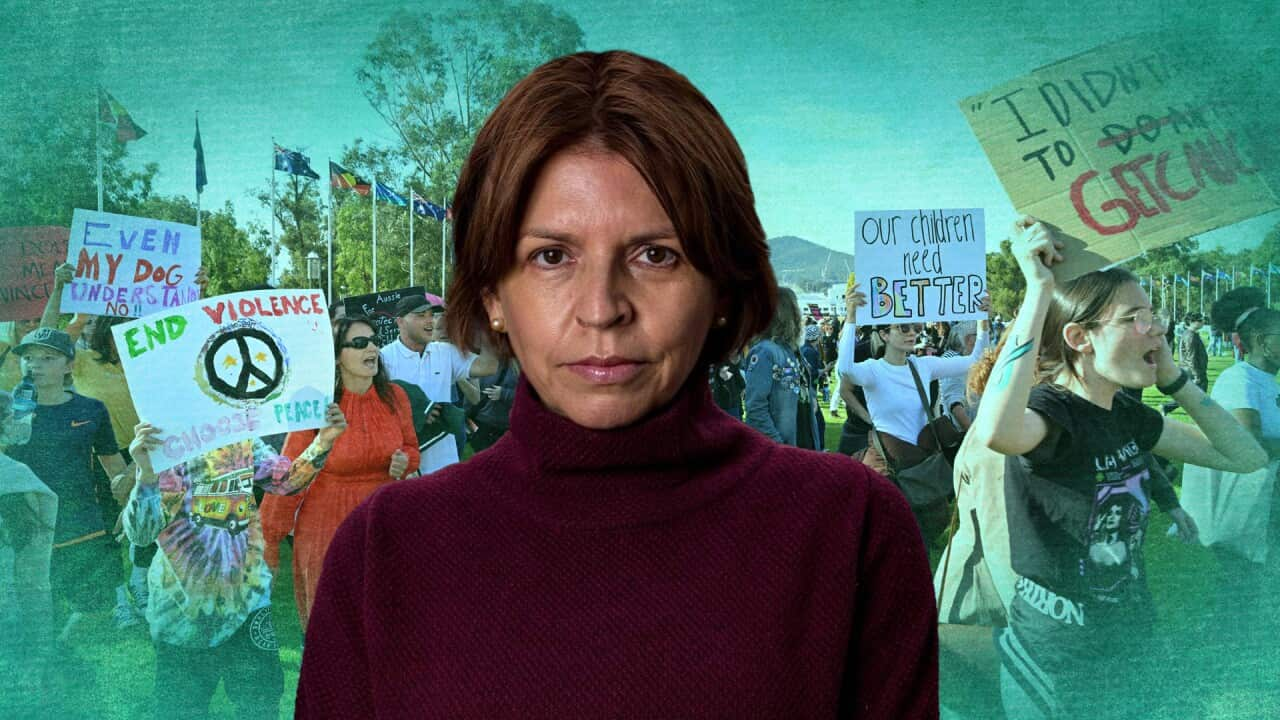

This week, Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal women met in Canberra for crisis talks on homicide and deaths of women.

Last week, Prime Minister Anthony Albanese announced the Leaving Violence Program, which will provide increased financial support for women to escape violence.

Almost $1 billion dollars will go towards financial support for women fleeing violent situations, with a one-off support payment worth $5000 dollars, as well as safety assessments and referral to support pathways.

Additionally, the government will take measures to address online hate towards women and toxic and violent masculinity.

But are the measures enough to combat a rampant societal problem?

The realities of violence against Indigenous women

Too many women are trapped in homes with violence due to poverty and lack of finances.

Aboriginal women are disproportionately affected by poverty and violence and need this help to escape.

In Western Australia, the Telethon Kids Institute in 2016 found that Aboriginal mothers are 17.5 times more likely to be a victim of homicide than non-Aboriginal mothers.

Nationally, Aboriginal women are 8 times more likely to be murdered than non-Aboriginal women and 32 times more likely to be hospitalised.

Globally, according to UN Women, 1 in 3 Indigenous women will be raped in her lifetime.

In Australia we know that Aboriginal girls are at high risk, yet little is done about this.

Safety assessments are critical.

Too often a woman is murdered when the risks to her are evident, and yet ignored by the justice system. This was the case in the death of whose ex-partner had only recently appeared in court on charges of rape and intimidation and yet was released on bail.

The NSW government announced an immediate review of bail laws.

The response of the women’s sector to the PM's announcement has been lukewarm because it didn’t respond to the critical underfunding of women’s Family and Domestic Violence services, which are turning hundreds of women a week away due to a lack of capacity.

CEO of Sydney women’s refuge Women & Children First, Gabrielle Morrissey, said following Wednesday’s meeting that “nothing proposed today will keep women safer tomorrow, next week or next month”.

The specialist Aboriginal Family Violence Prevention and Legal Services (FVPLS) also receive insecure funding tied to government cycles which compromises their ability to deliver the critical services.

This program funding is also limited to regional and remote areas and is unable to meet the needs of Aboriginal women in urban areas, who may be unable to access mainstream services that are at capacity.

There’s also questions about whether women can adequately access the funds, which appear to be a continuation of a 2021 commitment ‘Escaping Violence Payment’.

Unfortunately, an evaluation this year has found that .

Clearly, reforms are needed to ensure victims have improved access to these emergency funds.

Government policies don't keep Aboriginal women safe

On a positive note, the Albanese Government is now taking action to support Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women and children, with the addressing violence against Indigenous women.

This work is being overseen by a committee of Aboriginal women (and men) and government representatives, with SNAICC providing secretarial support.

The plan is expected to be launched in mid-2025.

It was hard fought for by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women. I advocated for it in 2016, and mechanisms to urge they adopt this as an official recommendation to the Australian government.

The PM’s announcement also comes off the heels of the WA Premier Roger Cook’s commitment of $94 million dollars in funding to address violence against women and in response to the WA Family and Domestic Violence Taskforce.

This seems positive, but Aboriginal women leaders and experts are not convinced.

Investing in more police and social workers, invariably non-Aboriginal people, working in non-Aboriginal institutions, has proven time again to be a failed response.

Many Aboriginal women especially will not call the police for help knowing this may not be safe or useful.

Systemic racism and lack of cultural safety in mainstream responses increase women’s trauma as children can be removed and taken by the state.

Women can also be dismissed or wrongly identified as aggressors rather than victims due to racial stereotyping and prejudice, which also rejects women’s right to self-defence.

'Nothing about us without us'

It was 20 years ago that the Gordon Inquiry in WA advised the government a ‘sea change’ was needed: Aboriginal communities must be empowered and supported to address violence.

The police and child protection approach eventually adopted was not that envisaged by the inquiry, established following the death of 16-year-old Noongar girl Susan Taylor.

This approach has not resulted in any decline in violence or made women safer. It has led to more Aboriginal children being removed and placed in the ‘care’ of the state, even though we know how harmful and damaging this can be to our children.

Aboriginal women for decades now have urged governments to tackle systemic reform and address racism and bias in the institutional responses.

We also need urgent investment into Aboriginal community-led solutions to end violence and support healing from trauma stemming from this violence and the violence of colonisation and ongoing practices such as child removal that were genocidal in their intent and impact.

We have still not been heard.

This must change.

Recently the Australian National Research Organisation on Women (ANROWS) supported a to accompany a UN communication ‘Seven Sisters’ on behalf of the families of murdered and missing Indigenous women in Western Australia.

There has never been justice for the victims and their families, and this is also a failure of Australia to address racism, and discrimination against Aboriginal women.

Aboriginal women are not staying quiet in the current political context.

At the crisis talks in Canberra on Tuesday, chaired by the Family Violence Commissioner Michaela Cronin, we spoke about the importance of Indigenous women's leadership and voices in reforming the responses, and the urgent need for systemic reforms to address safety for First Nations women.

Again, we call on non-Aboriginal women to address white privilege and hear our voices.

Too often white feminist approaches prioritise laws and policing, even though this hurts our women and children.

Stopping violence against women requires genuine allyship, commitment to addressing racism and intersectional discrimination, and willingness to undertake systems reform to the institutions that have been built on our unceded lands.

We say ‘nothing about us without us’ knowing that our voices and lived experiences of violence in all its many forms is vital to the solutions.

Dr Hannah McGlade is from the Kurin Minang people, she is a writer, lawyer and human rights expert. Dr McGlade is a member of the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues.