Queen Elizabeth II was the figurehead of the same Empire that invaded the sovereign nations of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

While some Indigenous people would invest in her the same hopes and pride felt by Commonwealth subjects around the world, a lot could never reconcile themselves with the very symbol of Aboriginal dispossession, while that dispossession continued.

The relationship between the monarchy and Aboriginal people, over the many decades of Elizabeth's tenure, saw some things change, and others remain the same, as their interactions over that time demonstrated.

Out of sight, out of mind

The first visits of Queen Elizabeth displayed the kind of whitewashing of history that typified the British Empire's approach to its various colonies, namely, that Australian history began with white arrival.

In the 50s, the existence of Aboriginal people was barely acknowledged by the monarch who represented an unbroken line of rule back to the First Fleet's invasion.

On her first visit in 1954, the Queen was kept removed from the peoples whose land her Empire had stolen. There were some vague and reductive displays of Aboriginal culture, such as a demonstration of boomerang or spear throwing, but the idea that there were many varied Indigenous cultures across the continent was still a bridge too far.

One event saw a white ballet company perform a dance entitled 'Corroboree', and don blackface in case the point was missed.

A notable exception was the meeting between the monarch and Albert Namatjira, then already a widely respected artist.

Albert Namatjira meeting Queen Elizabeth II in 1954 as Prince Phillip looks on. Source: Getty Images

Protest confronts the Queen

1970 marked the bicentenary of Cook's arrival on Aboriginal lands.

The Queen was in attendance to celebrate the occasion, which saw a reenactment of British soldiers firing muskets on the Gweagal people at Kamay.

Protestors threw wreaths into Botany Bay, aiming for them to drift past the Queen. When her royal yacht, the Britannia, sailed past them, they turned their backs in protest, holding banners aloft that read: "We're not asking, we're demanding."

In 1973, with the Queen in attendance, a descendant of Bennelong, actor Ben Blakeney, helped open the newly-built Sydney Opera House with an official welcome. A young David Gulpilil was there too, dancing as part of the festivities.

A young David Gulpilil was there too, dancing as part of the festivities.

Protestors gather in 1970 to lay memorial wreaths marking the occasion of Captain Cook's arrival on Aboriginal shores. Source: State Library of NSW

However, Elizabeth was again met by protestors on that same visit, and jeered when she ascended the steps of Parliament House.

Representatives of the Aboriginal Tent Embassy meanwhile handed Prince Phillip, the Queen's consort, a list of their demands which included Indigenous sovereignty.

Petitioned by leaders

It was not the last time the royals would be presented with a petition.

The tireless efforts of Aboriginal people, dating back to the very moment of white arrival, to assert their rights and sovereignty saw an increasing acknowledgement of their struggle on the part of the monarchy.

Michael Mansell presented the Queen with a petition for Aboriginal land rights at a reception in Hobart in 1977. She listened to his concerns that Tasmanian Aboriginals had been dispossessed of their lands by the same Crown she now represented, and had received nothing in return.

She received similar petitions during her visits in the 70s and 80s, and her tone began to change regarding First Nations issues.

In 1986 she told the Australian press that she was encouraged by the far greater “attention” that was being “given to the history and needs" of Aboriginal people and their descendants.

Michael Mansell presents the Queen with a petition for Tasmanian Aboriginal land rights in 1977. Source: Supplied

Reconciliation and Referendum

In 1999, a delegation of senior Aboriginal figures met with the Queen in the seat of British power, Buckingham Palace. It was a meeting of royalty: Queen Elizabeth had an extended audience with Pat Dodson, Peter Yu, Dr Lowitja O'Donoghue, Gatjil Djerrkura, and Professor Marcia Langton.

It was also a long time coming: it was the first audience granted to an Indigenous representative by a reigning British monarch since 24 May 1793, when Bennelong met King George III.

It was an interesting time in Australia's relationship with Britain, as the republic referendum approached. There were reports at the time that the Aboriginal luminaries would be seeking an apology for the historical and continuing wrongs the Queen's forebears had initiated.

Ultimately that never happened, but the delegation did discuss topics of reconciliation, and the continuing plight that the British invasion had caused in communities.

Pat Dodson described the meeting at the time as "extraordinarily beneficial", with the Queen interested in the discussion and asking many questions. The Yawuru man said it was "a quite significant difference to the way we're treated sometimes in our own country" by then-prime minister, John Howard.

'Interested to learn'

In the new millennium, on another trip to Australia, the Queen visited the outback NSW town of Bourke, population then 3500.

2CUZ FM, an Indigenous radio station that had been broadcasting since 1996, received a visit from the monarch. She was welcomed by the Ngemba Muranari troupe, who proudly wore paint and performed traditional dance.

Radio station manager Greg McKellar said the queen showed a key interest in Aboriginal culture during her 15-minute visit. He and his wife Francis also presented her with several gifts at the Muda Aboriginal Language and Cultural Centre.

Before leaving Bourke, the queen said she was "interested to learn that the rich aspects of Aboriginal culture are present in all the school’s programs, and I have seen for myself the Aboriginal language class being conducted in the gardens of the radio station.

"All communities need building with patience and understanding in ways such as these," she said.

The Queen is presented with gifts of a boomerang and a nulla nulla by Greg McKellar and his wife Francis at the Muda Aboriginal Language Centre. Source: Getty Images

Continuing advocacy

On the Queen's regular visits to the continent, Aboriginal people would consistently raise the issue of their rights with the monarch.

In April of 2000, Eastern Arrernte Elder Margaret-Mary Turner presented Elizabeth with a video of pleas from locals highlighting the Northern Territory's mandatory sentencing legislation.

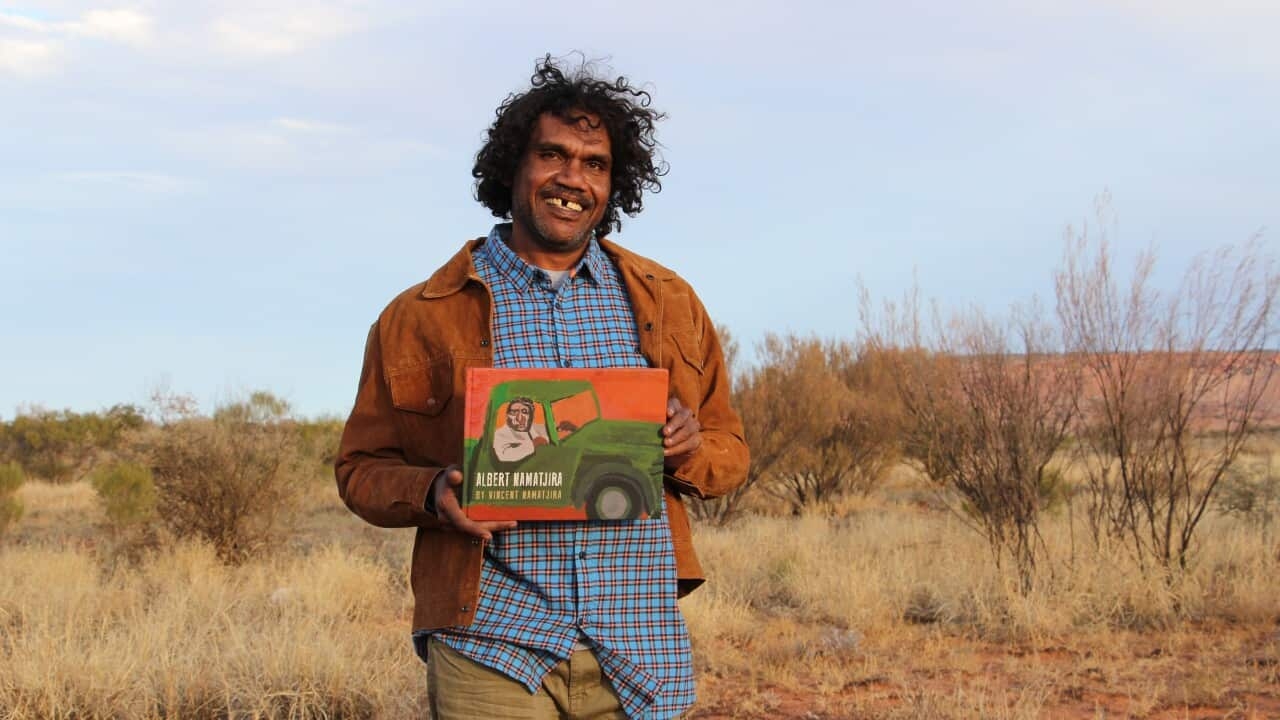

In 2013, 50 years after Albert Namatjira had met the Queen, his grandchildren Kevin and Lenie Namatjira also had an audience with the monarch. They used a 15-minute meeting at Buckingham Palace to call "for a better deal for Indigenous Australians".

One year later, in 2014, ‘Uncle’ Boydie Turner, grandson of Yorta Yorta campaigner William Cooper, delivered a petition to Elizabeth that Cooper had written to her grandfather, George V, in 1934.

It all falls within the centuries long fight to present to the very top echelons of power the injustices, from Crown to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, that were inherent in the very existence of that relationship.

Kevin and Lenie Namatjira meet with Queen Elizabeth and Prince Phillip in 2013. Source: Getty Images Europe