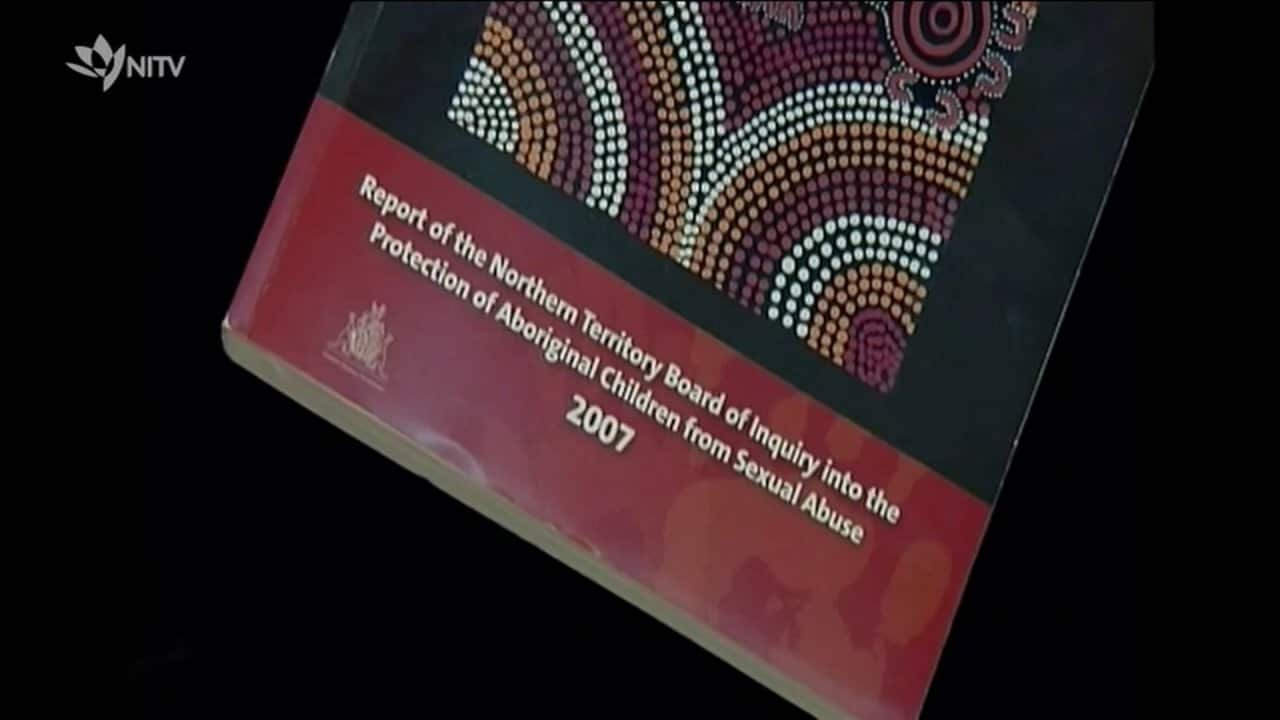

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children have never been more likely to be in out of home care.

But the Indigenous community-controlled sector, which is most likely to keep First Nations children safe and cared for at home with family, and connected to kin and culture, continues to be woefully underfunded, according to this year's report.

And in the same week that SNAICC, a national voice for our children, released Family Matters, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families who claim they have experienced racial discrimination resulting in the removal of their children in Western Australia and NSW launched legal action against the respective state governments.

First Nations children are 10.8 times more likely than their non-Indigenous peers to be in out of home care, the Family Matters report, which describes data related to child protection, found.

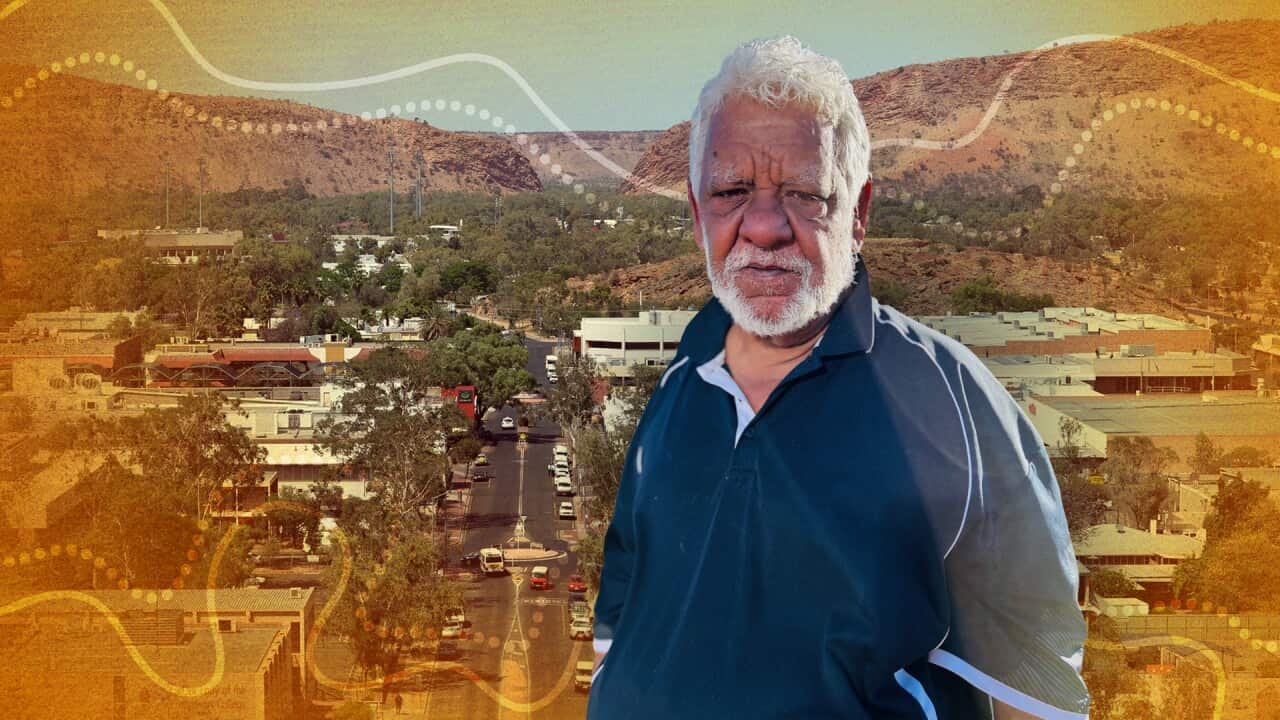

"It tells us the story of our deep disparity," SNAICC chief executive Catherine Liddle told NITV.

"It tells us that currently, 41 per cent of the children in out of home care are Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children.

"It also tells us that the Aboriginal community controlled services that have remit for responsibility for looking after these children only get 6 per cent of the resources required to work with their children and work with their families."

The data in the report shows that proportional investment in prevention and early intervention services has decreased in the past five years.

"An increase in proportional investment to prevention and early intervention cannot safely be achieved by simply shifting funding from already stretched child protection and out of home care systems," the report says.

"What is needed is the foresight of governments to invest more in – and recognise the long-term benefits of – prevention and early intervention that are demonstrated in the evidence."

Ms Liddle said that, despite this deeply concerning projection, there remains hope that this trajectory can be altered to achieve a reduction in Indigenous children in the child protection system.

And there's a roadmap - if governments live up to their commitments under the National Agreement on Closing the Gap and transfer decision-making and stewardship to First Nations communities, increase efforts and investment to support families and address the drivers of child protection intervention.

Ms Liddle said the report shows the positive impacts the Aboriginal community controlled sector is having in connecting Indigenous children with kin and culture.

"It shows how services are working to prevent and intervene in child removal and work to keep vulnerable children and families safe, supported and connected,” she said.

“However, what the 2024 data tells us is despite the positive trend among ACCOs, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children continue to enter and stay in the system at such a rate that they are grossly over-represented at every point of intervention.

“This over-representation grows as family interventions become more intrusive at each stage of the system, pointing to a systemic failure to respond and support children and families rather than issues driven at a community level."

Family Matters indicates that without substantial change in the way all governments work with Aboriginal organisations, the National Agreement on Closing the Gap’s target to reduce the over-representation of First Nations children in out-of-home care by 45 per cent by 2031 will not be met.

“In fact, this target is going backwards," Ms Liddle said.

“What’s most disappointing is that the solutions to these challenges are clear, and they have been articulated by communities for decades.”

The latest data also shows only 15 per cent of government funding in child protection is going towards early intervention and family support services while 85 per cent goes towards the delivery of OOHC services.

“The reason the gap is widening is simple - federal, state and territory governments are not investing in the programs and projects that work to close it," Ms Liddle said.

“Governments must get serious about transforming the way they do business with ACCOs by transferring authority and adequate resourcing that will keep families together and prevent the landslide of children entering the misnamed protection system.

Our sector, communities and families are sick of seeing our children removed.

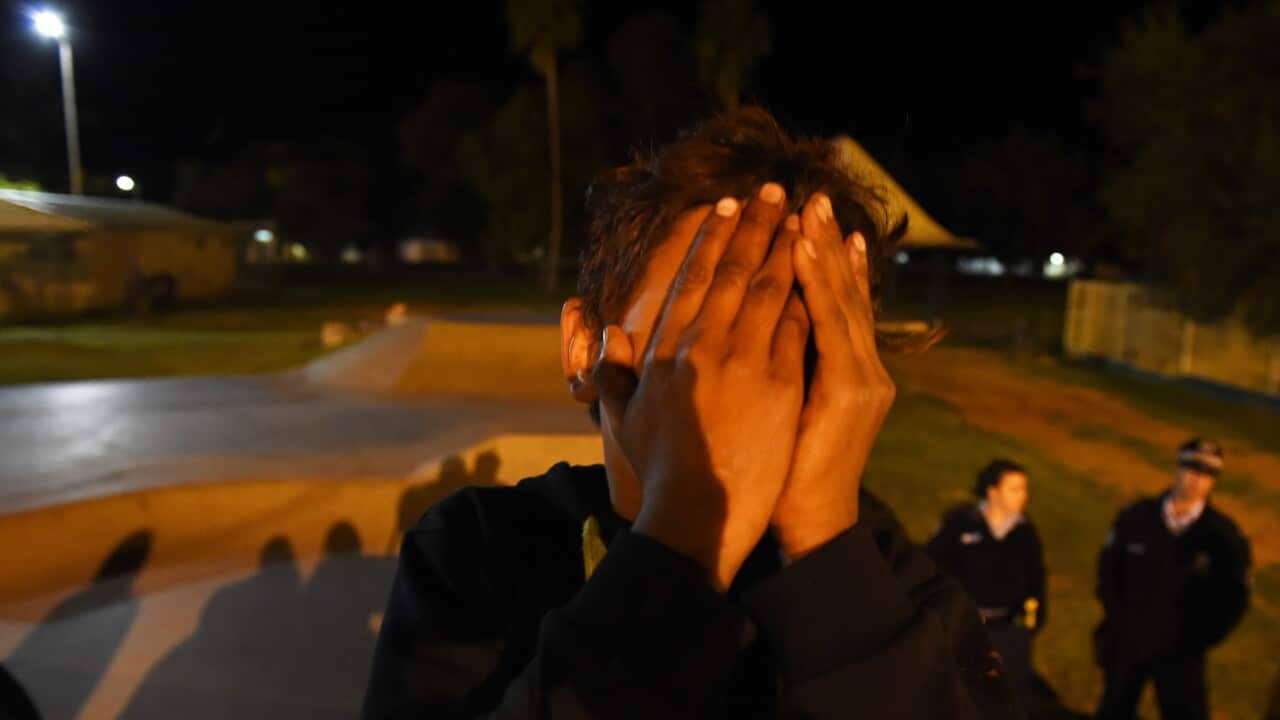

"The number of children who are crossing over from child protection into youth justice systems is increasing, yet there continues to be a focus at the tertiary end of responses.

“We have major NGOs committed to transitioning out-of-home care and support services to ACCOs through the work of Allies for Children.

"It is way past time for governments to do the same.”

Class action launched in NSW and WA

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families who claim they have experienced racial discrimination resulting in the removal of their children in WA and NSW have launched legal action against the respective state governments.

Shine Lawyers' special counsel Caitlin Wilson is leading the class action on behalf of the families.

Ms Wilson said the families allege there has been widespread racial discrimination across a number of state governments, resulting in the removal of Indigenous children from their families and a loss of cultural connection.

“First Nations children are consistently and significantly over-represented in out of home care, and at the present time, WA boasts the highest rate of over-representation in the country," she said.

"This class action alleges that this is largely because of the discriminatory conduct of the department throughout each of the various entry points into the child protection system."

Shine client and mother of four Sarah had her children taken into state care when they were young.

Her eldest three children, who are now 20, 19, and 18, were placed in care for seven years, while her youngest, aged 11, was taken five days after birth and remained in care for nine months.

During their time in state care, one of Sarah’s children was subjected to sexual abuse, the law firm says.

Sarah worked toward reunification and had her parental rights reinstated.

However, rates of reunification are low, with only seven per cent of Indigenous children reunited with their families in WA, and just two per cent in NSW.

National Suicide Prevention and Trauma Recovery Project director Megan Krakouer has supported a number of families who have experienced the removal of children.

She welcomed the class action.

“We are not an industry - our children are not statistics," Ms Krakouer said.

"The time to act is now.

"I have witnessed too many tears of families, of children, the power imbalance, and cultural theft.

"For every 10 children removed, only one is reunified -this is the Blak struggle."

Shine is also investigating child removals in Victoria and South Australia.

Ms Liddle says the solutions are clear, if governments want to see positive change, they need to start rethinking the way they approach child protection.

"We need to see governments at all levels across all the country invest in the programs and the services that get the best results," she said.

"Now the Family Matters report says it and it says it clearly: where Aboriginal community controlled services are working within their communities and working with families who are experiencing extreme vulnerabilities, they get different results.

"They get healthier children, they get children that stay at home.

"They get strong families, and they get strong communities."

13YARN 13 92 76

Lifeline 13 11 14