Warning: this story contains the name of a deceased Aboriginal person and violent details of a massacre.

Once you see him, you cannot unsee him.

He is simply referred to as ‘No. 41: Mrs Blair’s Aborigine’.

But who was he? How does he end up on Wurundjeri Woi Wurrung Country and in a 19th century group portrait of the who’s who of Melbourne?

His name was Lani Mulgrave Blair.

Lani Mulgrave Blair.

Kahler, born in Austria, arrived in Melbourne in 1885 and set up a successful portrait practice but is best remembered for three major works depicting Melbourne’s Flemington racecourse.

immortalises the day – Saturday, October 30, 1886 – when Trident won the Victoria Racing Club Derby.

It’s an important nineteenth century group portrait of around 200 figures and featuring many prominent citizens of Melbourne, including Sir Henry Brougham Loch (Governor of Victoria) and the Duke of Manchester.

Reprints of the painting are housed in Canberra in the National Portrait Gallery, the National Library of Australia, the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS) and the original hangs in the Victorian Racing Club at Flemington.

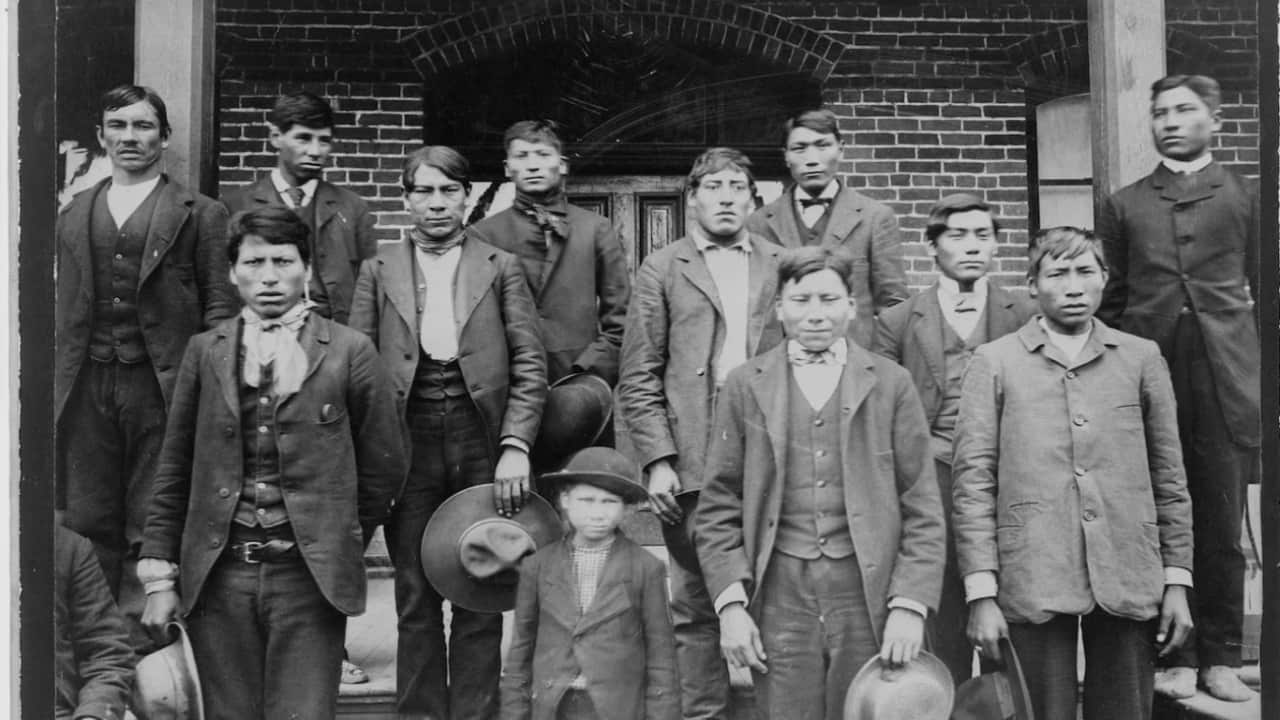

Aboriginal men and boys from the Mulgrave district.

He was born around 1882 in the Mulgrave River region, about 40km south of Cairns at the foot of the Bellenden Ker Range.

He was of the Mallanbarra people of the Yidindji nation. (Eight clan groups make up the Yidindji nation.)

Aboriginal camp on the Mulgrave River. Credit: Archibald Meston Album 1905

In the early 1880s, alluvial gold had been found in the region and the Mulgrave River Goldfield was proclaimed.

Steam ships made regular trips up the coast and into the Mulgrave River to drop off both supplies and men seeking their fortune.

As the settlements spread out, the clans and family groups of the Yidindji were decimated following a series of massacres or ‘dispersals’ from 1880 onwards.

Canoeing on the Mulgrave River. Credit: John Oxley Library

That massacre was recounted to anthropologist Norman Tindale in 1938 by Jack Kane, who had arrived in Cairns in 1882 and who actually participated in the ‘dispersal’ when he was 18 years old.

Kane described the events:

“At Skull Pocket police officers and native trackers surrounded a camp of Yidindji blacks before dawn, each man armed with a rifle and revolver.

“At dawn one man fired into their camp and the natives rushed away in three other directions. They were easy running shots, close up. The native police rushed in with their scrub knives and killed off the children.

"I didn't mind the killing of the ‘bucks’ but I didn't quite like them braining the kids.

“A few years later a man loaded up a whole case of skulls and took them away as specimens.”

Timothy Bottoms, a Cairns-based historian and author, says the Queensland frontier was devastatingly violent.

“Many tens of thousands of Aboriginals were killed on the Queensland frontier,” he wrote in his 2013 book Conspiracy of Silence – Queensland’s frontier killing times.

“I have mapped only some of the massacres in colonial Queensland; it is my belief that it does not represent the true nature of violence on the frontier.

One can understand why white colonial Queenslanders were ashamed of what they allowed to happen, but why the conspiracy of silence since then?

Surviving the massacre, Lani was ‘taken’ aged around 2 years old into Cairns and then onto Melbourne, where he was ‘given’ to one of the most prominent medical men in Melbourne in that era, Dr John Blair, presumably to work as a domestic servant.

Dr Blair, originally from Scotland, was influential in the foundation of the Prince Alfred Memorial Hospital.

Dr John Blair.

Writing in Melbourne’s The Argus newspaper in April 1930 they told how Dr Blair had a theory that, given equal chances, “the Aboriginal brain would compare favourably with the 'white' brain" or that an infant Aborigine trained and "educated from birth would be equal to any British subject or scholar.

READ MORE

Servant Or Slave

"To test his theory Dr Blair arranged with a captain of one of the inter-colonial steamers to obtain a Queensland native for him.

“The first child died on the voyage down. A second attempt resulted in Lani being landed safely,” they wrote.

Mary Blair and the baby she named Lani, who was taken from Far North Queensland to Melbourne after a massacre.

"As was the custom then among people who lived in good style and could afford the luxury, Dr Blair and his wife Mary had had a staff of Indian servants. One of them - the butler named Lani - remained a good and faithful servant until he died at Sorrento (on Mornington Peninsula) where he lies buried."

Mrs Blair named Lani after her faithful butler.

Lani Mulgrave Blair and Mary Blair.

According to correspondence in The Argus, Lani led a happy life playing in the local parks with his friends and his dog, a Scotch terrier named Donald Dinnie, under the watchful eye of his nurse.

He spent holidays and weekends with the Blairs at their sanitorium in Sorrento, where he was habitually dressed in a sailor suit.

Dr Blair died at the age of 53 in 1887.

In 1889 Lani won a prize for writing, and again in 1890, when he was given a special prize of a writing desk. He also learned to speak French.

Lani played football, competed in bicycle races and became a splendid cricketer for the Sunbeams cricket team in East Melbourne.

After moving to St Kilda and attending school there he was apprenticed to the architect Sydney H Wilson, who declared that ‘he had considerable skill in drawing.’

In 1900, after he had served two years as a pupil, one Saturday afternoon he ventured into Albert Park Lake - with the result that he caught a chill and succumbed to pneumonia.

Lani Mulgrave Blair, who died aged 17.

Mary Blair lived until 1921, her final years in the Kew Hospital for the Insane.

Dr and Mrs Blair, and their adopted son Lani are buried in the Presbyterian section of Melbourne General Cemetery.

The inscription says: "Our dearly beloved Lani, died January 18, 1900, aged 17 years."

Lani never made it back to his country or the waters of the Bana Baddi.