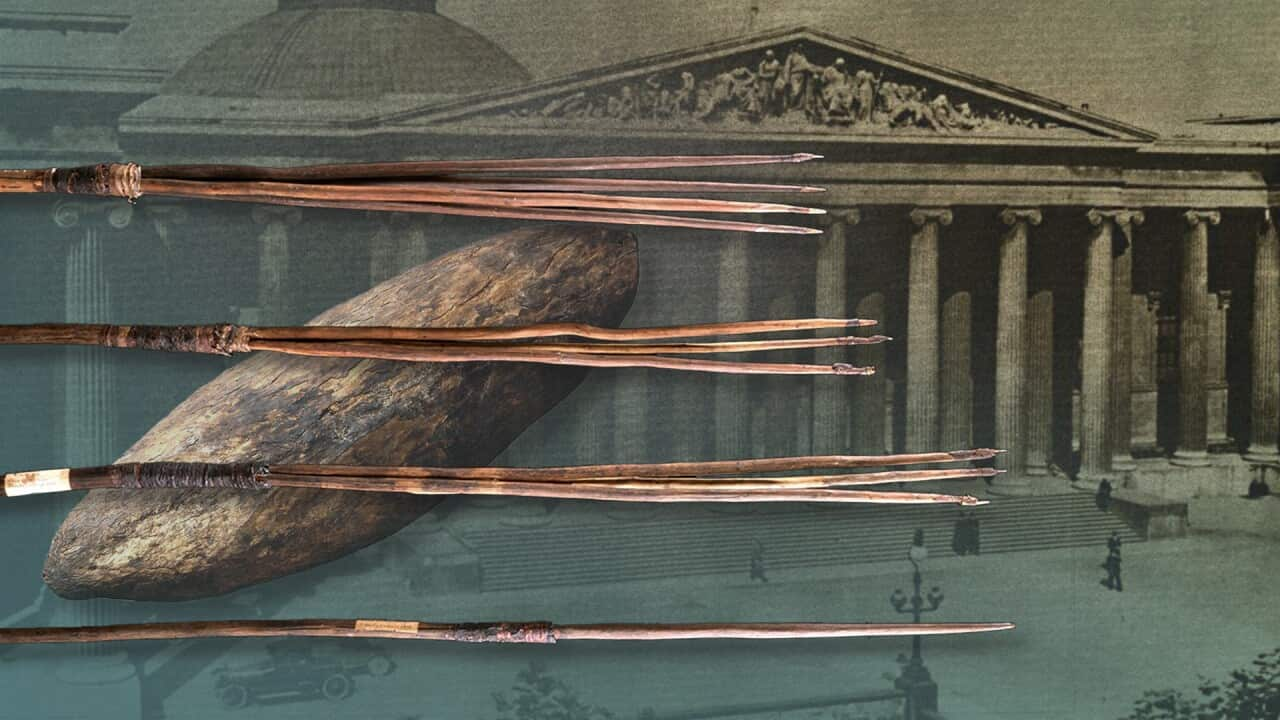

Recently, the Gweagal Spears made a welcome visit to Gadigal Country on a three-month loan.

It was their first appearance on these shores in 250 years. It's believed those same spears were taken by Captain Cook during his first, foreboding pass of Dharawal Country in 1770.

It is one of the first acts of dispossession visited upon First Nations peoples.

Over the next two and a half centuries the art, artefacts, human remains and lands of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people would be taken from them, with the objects often transported overseas.

On rare occasions they were gifts or bartered products; far more often they were stolen.

Today, there are many thousands, tens of thousands, of such items in museums, institutions and private collections all over the world.

Gweagal people observe Cook's arrival at Kamay. Though the Gweagal are depicted aggressively, the spears were actually used solely for fishing. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Repatriation efforts

The efforts of First Nations people to see the return of their cultural heritage from overseas have been many, varied and long-running.

They can range from personal campaigns of descendants, more formal efforts by land councils, or institution-level repatriation programs.

The Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS) leads the 'Return of Cultural Heritage' initiative, established in 2018. They work with First Nations peoples and international museums and individuals to negotiate the possible return of cultural heritage items.

In many cases, these efforts are met with stubbornness, but sometimes fruitful relationships are cultivated between Traditional Owners and institutions. Though the ultimate goal is most often to have artefacts permanently repatriated, sometimes the resources and facilities necessary to preserve the items do not exist on Country. Chairman of the Gujaga Foundation Ray Ingrey, who helped negotiate the visit of the Gweagal Spears from Cambridge University, said for the time being, it was more important the artefacts were preserved for future generations.

Chairman of the Gujaga Foundation Ray Ingrey, who helped negotiate the visit of the Gweagal Spears from Cambridge University, said for the time being, it was more important the artefacts were preserved for future generations.

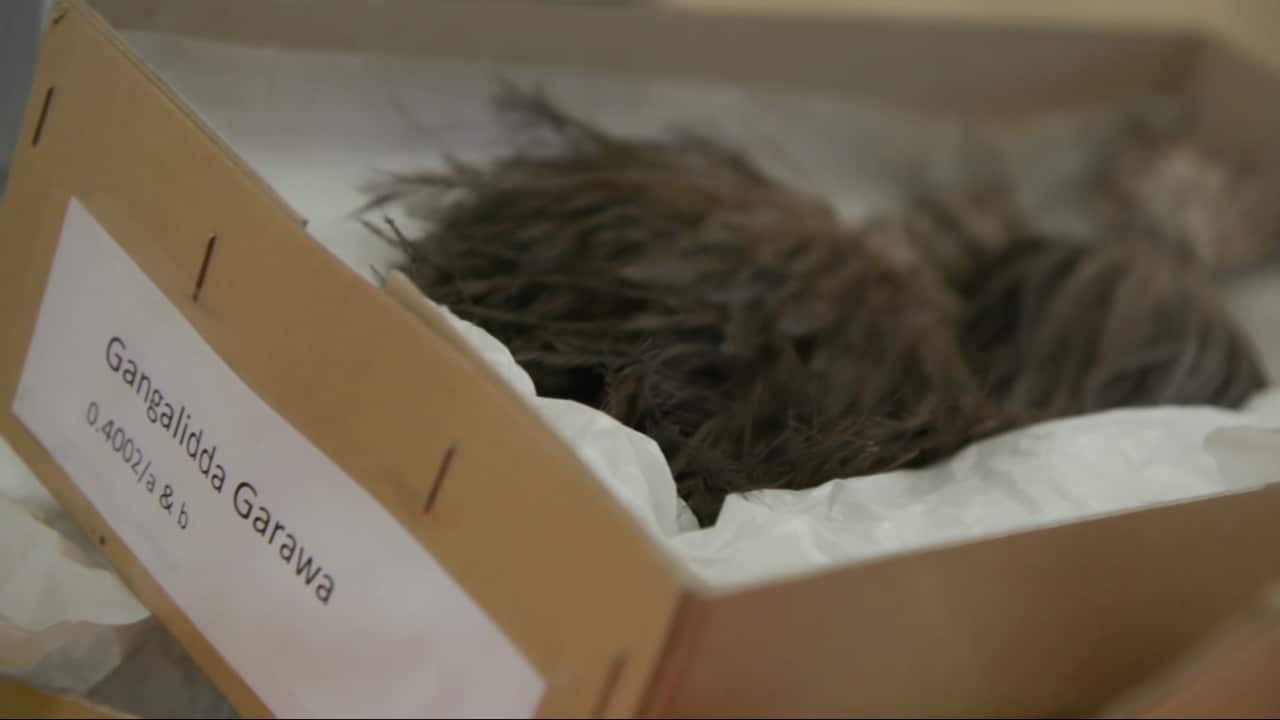

The kind of facility necessary to preserve the spears does not exist on Dharawal Country. Source: Supplied

"For now, as long as our Elders are happy that they've had enough time with them, we'll be happy to send them back and then start to have those conversations around when they're to come back here on a longer term basis."

The innumerable objects that exist in collections overseas include thousands of small trinkets, shells and stones found in middens around the country.

They also include works of art, tools and jewellery of incredible beauty and craftsmanship.

Here are six significant objects currently not on Country.

The Gweagal shield

The Gweagal Shield held at the British Museum. It is a powerful symbol of First Nations resistance. Source: Supplied: British Museum

It bears a tell-tale hole in its face, evidence, historians suspect, of gunshots, a violent response from the British to the appearance of the Gweagal.

It is currently kept at the British Museum. The institution is notorious for being one of the international museums least willing to engage in repatriation talks, either with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, or indeed any of the other nations their exhibits were stolen from.

"There's 6,000 Aboriginal artefacts in the British Museum," an AIATSIS representative told the ABC in 2016.

"The process of connecting people up with their lost stuff is ongoing."

Wallaby-teeth necklace

This necklace resides in the collection of the British Museum. Source: Supplied: British Museum

It is another item currently in the possession of the British Museum, which holds several such necklaces of varying provenance.

It is constructed from 49 teeth of a swamp, or black wallaby. Teeth were often used for decorative or functional purposes.

The roots of the teeth are bound with sinew, and suspended from a strip of brown skin through pierced holes. The ends of the strip form ties around the back of the neck.

"With the wallaby teeth [necklace]... It’s a strange feeling, that you come back with objects that have been held off country for 200 years and you say, ‘Look at these, these are yours, but not yours'," said Gunditjmara Elder Denise Lovett in 2014.

"Even physically they are not ours because they haven’t been given back to us."

‘Kaawirn Kuunawarn (Hissing Swan), Chief of the Kirra Wuurong Blood Tip Tribe’, about 1820–89, wearing a wallaby tooth necklace. Source: State Library of Victoria

Yolgnu Baijinn figures

A Baijini figure, carved by Yolgnu man Binyinyuwuy Djarrankuykuy. Source: www.kluge-ruhe.org

Binyinyuwuy was a fascinating Yolgnu man who defended the Northern Territory during the Second World War, became an antagonist to white occupation in the years after, and whose artistic skill inspired an art practice that continues in Yurruwi (Milingimbi Island), off Arnhem land, to this day.

This figure represents Baijini, a mythical people mentioned in the Djanggawul song cycle of the Yolngu.

It was collected by Edward Ruhe, a Professor of English at the University of Kansas, in 1965. Ruhe amassed one of the largest private collections of First Nations art in the world before he died in 1989.

The collection was bought by media mogul John Kluge in 1993, and currently resides in Charlotttesville at the Kluge-Ruhe Museum, the only museum in the United States which solely exhibits First Nations works.

William Barak paintings

A Sotheby's employee views the painting 'Corroboree' by Wurundjeri artist William Barak. Source: AFP

His paintings now adorn the walls of the nation's most prestigious galleries, especially at the National Gallery of Victoria, which stands on his Country.

Many, however, exist in the private collections of international buyers, such as the work above, 'Corroboree'.

In June 2016, another drawing of Barak's went to auction, setting a record at the time, selling for over $500,000 dollars.

Leading up to the sale, a number of Barak's descendants, represented by the Wurundjeri Council, crowdsourced donations in an effort to buy the painting for themselves. Unfortunately, the sum raised was not enough to secure the sale.

Message stick

The parallel lines running the length of the stick denote a wire fence, which contained an area where emu and wallaby could be hunted. Source: www.prm.ox.ac.uk

The designs etched into its surface ostensibly make the offer of a hunt: contemporary scholarship held that the sender was proposing to hunt emu and wallaby at a station near Clermont, in Queensland.

The parallel lines running the length of the stick denote a wire fence, that presumably contained the area.

The ever-expanding influence of colonialism is evident here in the vibrant blue, a product of Reckitt's laundry powder.

Such message sticks were always painted. The sticks could bear messages of invitation, conflict or death, and offered the bearer protection as they travelled through different tribes' Countries.

Pukumani grave posts

The Pukumani grave posts, currently held in the extensive Vatican museum. Source: www.museivaticani.va

The grave posts are a product of the Tiwi Islands, and represent part of the deeply spiritual process around farewelling a member of the community.

The poles are crafted for the funeral ceremony, and represent the cycle of life, death and rebirth, with the engravings and adornments representing the person who has died.

The poles are left to degrade when funeral proceedings are complete.

These poles were produced in the early 20th century. They were submitted to the Vatican in 1925 after Pope Pius XI put a call out to the world's Indigenous Catholics to donate works they thought best represented their culture.

The works came from all over the globe, including 300 objects from northern and western Australia, donated by Aboriginal Catholics.