Some of these included compulsory leasing of land, prohibitions on alcohol and pornography and welfare quarantining. It also saw a large increase in budgets for law enforcement and child protection, along with housing and health services. Many of these measures were continued under the “Stronger Futures in the Northern Territory” policy from 2012, which remains in place today.

The initial justification for the Intervention made by Indigenous Affairs Minister, Mal Brough, was that paedophile rings were operating in Aboriginal communities. These allegations were refuted by the Australian Crime Commission in 2009 after thorough investigation. However, many other serious social problems affecting Aboriginal communities including alcohol related harm, high rates of family violence and incarceration, were also put forward as justification for the draconian new regime. Sadly, despite more than $2 billion being budgeted by the Commonwealth for the Intervention and associated policies since 2007, many of the social problems facing communities have actually become worse.

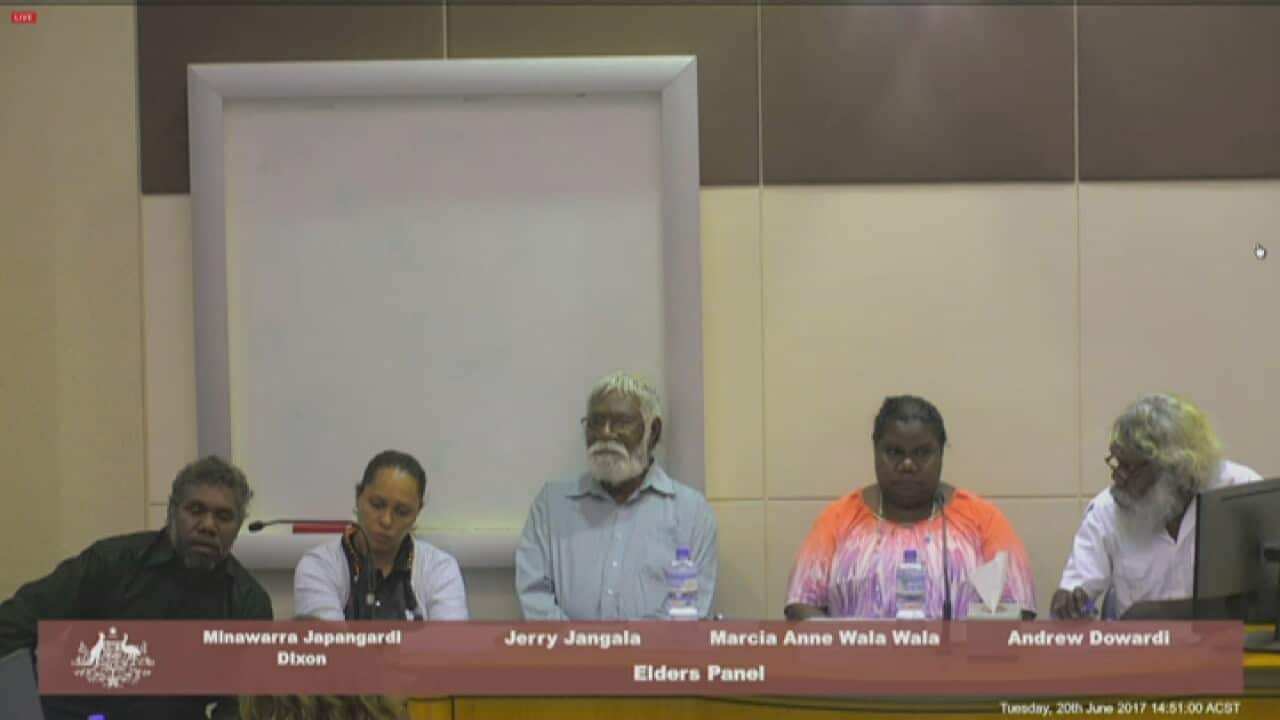

Source: NITV News

1. Many more Aboriginal children are being forcibly removed from their family and culture

The Intervention was accompanied by a massive injection of Commonwealth funding for "child protection” services in the NT. The NT Department of Children and Families budget increased from approximately $10 million in 2006 to $36 million in 2015. Overwhelmingly, these resources are focused on surveillance and removal of Aboriginal children, rather than support for struggling families. The cost of keeping a child in “out of home care” in the NT is upwards of $100,000 per child per year.

According to figures from the Productivity Commission, the number of Indigenous children in “out of home care” has increased more than threefold, from 265 children in June 2007 to 920 in June 2016. Over the same period, the number of non-Indigenous children in care slightly decreased. The rate at which non-Indigenous children are being placed on child protection orders has decreased markedly from 113 in 2006-07 to just 48 in 2015-16.

Meanwhile, the rate of placement according to the ‘Aboriginal child placement principle’, supposedly mandated by NT law, has decreased from 56% in 2006-07 to just 36.2% in 2012-13. The current NT Royal Commission has heard horrific stories of children, including newborn babies, being forcibly taken hundreds of kilometers away from their communities, even interstate, losing all contact with their family and culture. Some Aboriginal community leaders before the Commission have described this as a stolen generation.

Source: NITV News

2. Punitive measures have not increased school attendance

The NT Intervention has been accompanied by new measures which penalise parents whose children are not attending school. The School Enrolment and Attendance Measure (SEAM) introduced as a pilot in 2008 and expanded from 2013 makes welfare payments conditional on school attendance, while the NT government has run a parallel system of fining parents of truants. Changes to social security legislation introduced in 2010 link exemptions from income management school attendance. Despite this, the rates of school attendance of Aboriginal children under the Intervention have gone backwards.

Government monitoring reports looking specifically at “prescribed communities” under the Northern Territory Emergency Response (NTER) legislation showed that attendance rates dropped in both primary and secondary schools under the NTER, with overall rates declining from 62.3% just before the Intervention to 57.5% in 2011.

Less specific, more recent figures show that the situation has still not improved. Figures from the Productivity Commission “Overcoming Indigenous Disadvantage” reports show the Indigenous attendance rate in “remote” NT schools in 2009 was 80.2% and in “very remote” schools was 61.8%. The same figures in 2015 had declined to 78% in “remote” NT schools and 61.6% in “very remote” schools.

Source: Fairfax

3. The Intervention saw an increase in youth suicide and huge spike in self-harm

Monitoring reports released by the Commonwealth tracking social indicators in “prescribed communities” document a massive increase in reported incidents of attempted suicide and self-harm in the opening five years of the Intervention.

In 2006-07 there were 57 reported incidents. In 2011-12 there were 316 incidents. This is an almost six fold increase. Commenting on the increase, then Social Justice Commissioner Mick Gooda said, "One view put forward is that these figures reflect an increased police presence in communities which caused incidents to be discovered which would have previously gone unreported. I harbour serious doubts about this being the main explanation for an increase of this magnitude.”

Over a similar period there was a big increase in the rate of youth suicide. The 2012 Indigenous Social Justice Report said:

"In the Northern Territory between 2006 and 2010, the rate of suicide for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people aged 10-17 was 30.1 per 100,000 compared to rate for non-Indigenous people in the same age bracket of 2.6 per 100,000. These rates for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people have increased 160% when compared to the previous period of 2001-2005. In contrast, non-Indigenous suicide rates have reduced to about a third of the previous period’s levels. The rates of suicide of young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander females are particularly shocking. Girls makeup 40% of youth suicide in the Northern Territory when the national average at this age is less than 10%.”

More recent suicide figures for this age bracket are not currently available, so we cannot draw direct comparisons with the period between 2010 and today. However, 2014 ABS statistics showed that both the overall NT Indigenous suicide rate and the rate for under 25s had not decreased on earlier data and remain the highest rates of any Australian jurisdiction.

Nation-wide, the suicide rate in Indigenous communities is estimated to be 40% higher than the rate of non-Indigenous suicide. Source: AAP

4. The Intervention housing program has had a minimal impact on shocking rates of overcrowding

The NT Intervention was accompanied by the Strategic Indigenous Housing and Infrastructure Program (SIHIP), with $647 million budgeted to construct 750 new houses and a major renovations drive across communities. Extra funding allocated through the Stronger Futures period means that more than 1000 new houses have now been built in NT communities since the start of the Intervention.

There has been minimal improvement in shocking rates of overcrowding during this period. According to Productivity Commission figures, the proportion of Indigenous people living in overcrowded housing has decreased from 59% in 2008 to 53% in 2014. These improvements are no greater than the national average, and are still more than twice the rate of Indigenous overcrowding in any Australian jurisdiction.

related article:

Voices from the Frontline - 10 years on from the NT Intervention

In May this year, David Ross from the Central Land Council argued recent Commonwealth investments were “a drop in the ocean compared to the need”. Mr Ross pointed out that the Little Children Are Sacred Report that was used as a pretext for the Intervention called for the immediate construction of 4000 houses and 400 additional houses each year until 2027.

Under the Intervention, funding for new housing and for housing maintenance has been contingent on Aboriginal communities signing over township lands, to the Commonwealth, under long term leases of between 40 - 99 years. Hundreds of millions of dollars’ worth of housing stock previously built and owned by locally controlled Aboriginal housing organisations has been transferred to Commonwealth control under the Intervention.

The Federal Government announces an independent review into the state of Indigenous housing in remote communities. Source: AAP

5. Income Management has made life harder for many and remains racially discriminatory

The NT Intervention forced all recipients of Centrelink in prescribed communities onto Income Management. Under this system, half of regular payments and all lump sum payments quarantined and cannot be paid as cash. Use of quarantined payments must be negotiated with Centrelink and since 2008 has been most often paid onto a ‘BasicsCard’ that can only be used on approved items at approved stores.

In 2010, the Gillard government reinstated the Racial Discrimination Act with respect to Income Management. Instead of just Aboriginal communities, anywhere in Australia can now be declared an “income management area” and the whole of the NT was declared. Since then, the scheme has been extended to other areas in Australia, most of which have large Aboriginal populations. The NT scheme is still far more draconian than any other, targeting all young people or long term unemployed on benefits, instead of specific groups referred by social services. The NT scheme still makes up more than 80% of all people on income management Australia wide.

Approximately 90% of people on income management in the NT are Indigenous and 80% of all people across Australia on income management are Indigenous.

A 2012 government commissioned review of income management surveyed over 800 people on the system. More than two-thirds of people said that income management is discriminatory. Similar numbers report feelings of embarrassment arising from income management, and three quarters feel it is unfair. A majority said the scheme had made their life harder or not improved things.

The Commonwealth’s own Joint Parliamentary Committee on Human Rights found in a 2016 review that Income Management in the NT was racially discriminatory according to standards outlined in UN conventions and recommended an end to the blanket targeting of welfare recipients taking place under the NT scheme.

More than $1 billion has been allocated from the Commonwealth budget for income management Australia wide since the launch of the NT Intervention. The estimated administrative cost per person per week is $80. Despite this enormous expense, the government commissioned review of income management in the NT argued in their final 2014 report:

The evaluation could not find any substantive evidence of the program having significant changes relative to its key policy objectives, including changing people’s behaviours.

More general measures of wellbeing at the community level show no evidence of improvement, including for children.

The evaluation found that, rather than building capacity and independence, for many the program has acted to make people more dependent on welfare.

The NT Intervention forced all recipients of Centrelink in prescribed communities onto Income Management. Source: AAP

6. The abolition of the Community Development Employment Projects (CDEP) has created mass unemployment and exploitation

Prior to the NT Intervention, approximately 7500 people were employed across Aboriginal communities in the NT working on Community Development Employment Projects (CDEP). CDEPs were mostly local Aboriginal government councils running municipal and other community services. The scheme was abolished under the Intervention and CDEP participants were transferred from wages onto Centrelink payments.

The Rudd government introduced an NT Jobs Package to replace CDEP positions with “real jobs”, creating 2241 new positions. However, figures gained through Senate estimates in 2011 showed 61 per cent of these positions were only part-time and many are on the lowest level of public sector pay. The net result of this reform process has been a loss of many thousands of waged jobs. Aboriginal unemployment rates across remote Australia have skyrocketed from 11 per cent before the Intervention, to 28 per cent today. This figure does not register the many thousands of unemployed people not registered with Centrelink.

An exploitative Work for the Dole scheme has replaced CDEP. Under the current scheme, called the Community Development Program (CDP), Newstart recipients are required to work for 25 hours per week to receive their entitlements. Often this is municipal work and private companies can also use CDP participants without paying them wages. There are no protections under industrial law and payment is well below award wages. Many CDP workers are on Income Management, meaning they only receive approximately $5 cash per hour for their work.

If CDP workers do not attend work they must be docked one days “pay” and can be cut off Centrelink entirely for up to eight weeks. At a Senate Estimates hearing in March 2017, the Prime Ministers Department confirmed that more than 200,000 breach notices have been handed out since CDP began in July 2015.

Aboriginal unemployment rates across remote Australia have skyrocketed from 11 per cent before the Intervention, to 28 per cent today. Source: NITV

7. Restrictions on courts considering Aboriginal culture, custom and law in bail and sentencing decisions continue

The Northern Territory National Emergency Response Act 2007 prohibited courts from considering Aboriginal culture, custom and law when making bail and sentencing decisions in the Northern Territory. This was a violation of principles of equality before the law and rights to a fair trial. All other groups in Australia have a right for all of their circumstances to be considered when courts are making bail and sentencing decisions - including their culture and customary obligations.

These laws did not only impact on sentencing for crimes committed by Indigenous people. For example, in 2007 a construction company dug a pit toilet on an Aboriginal sacred site at Numbulwar in the NT Gulf Country while building a compound for the new Government Business Manager installed by the Intervention. They were only fined $500 for this and, on appeal, the NT Supreme Court ruled that the cultural harm caused could not be considered by the court.

Under the Stronger Futures legislation introduced in 2012, changes were made to exempt matters involving Aboriginal heritage protection. But the legislation NTER provisions prohibiting consideration of customary law in bail and sentencing in the NT are now enshrined in the Crimes Act, with no sunset clause.

The NT National Emergency Response Act 2007 prohibited courts from considering Aboriginal culture, custom and law when making bail and sentencing decisions. Source: AAP

8. The number of Indigenous people in prison has exploded

According to figures from the Australian Bureau of Statistics:

The number of Indigenous men in prison has doubled over the past 10 years, from 668 in March 2007 to 1,327 in March 2017.

The number of Indigenous women in prison has increased more than three-fold from 30 in March 2007 to 106 in March 2017.

The current Royal Commission investigating abuse of children in youth detention reports that between 2006 - 2016 the number of children and young people entering detention more than doubled, from 120 to 254.

The number of young Aboriginal females entering detention increased from just 5 in 2006 to 48 in 2016.

Indigenous adults make up 84% of the NT prison population and Indigenous children and young people make up 94% of the NT youth prison population.

If the NT were a country, it would be second only to the United States in terms of rates of incarceration.

Indigenous adults make up 84% of the NT prison population and Indigenous children and young people make up 94% of the NT youth prison population. Source: Getty Images

9. Discriminatory alcohol bans remain in force and there is no evidence they have reduced harmful drinking

Prior to the NT Intervention, many remote communities had taken initiative to have dry areas established under provisions of the NT Liquor Act.

The Northern Territory National Emergency Response Act 2007 established blanket bans on alcohol across Aboriginal land. Police were given powers to enter homes and vehicles on Aboriginal land without a warrant to enforce this prohibition. The restrictions were extended for a further 10 years under Stronger Futures legislation introduced in 2012, but with increased penalties. Penalties under this law include the possibility of a 6 month jail sentence for possessing a single can of beer on Aboriginal land.

Stronger Futures laws also introduced the possibility of community negotiated “alcohol management plans” to potentially replace the blanket restrictions. However, a 2016 review by the Joint Parliamentary Committee on Human Rights found: “All of the existing alcohol restrictions imposed by the NTNER, and continued by the Stronger Futures measures, remain in place across the NT. As at late 2015, only one AMP has been approved by the current minister… for the Titjikala community. In that case, the AMP operates alongside the existing alcohol restrictions; it does not replace those restrictions. In addition, the current minister has refused to approve seven AMPs submitted by community groups.”

The review also found, "the measures limit the right to equality and non-discrimination as they directly discriminate on the basis of race” and that “the government has not produced any evidence as to the effectiveness of the Stronger Futures measures in reducing alcohol related harm”.

The Northern Territory National Emergency Response Act 2007 established blanket bans on alcohol across Aboriginal land Source: NITV News

10. Extreme rates of family violence have not decreased

The extreme rates of family violence in many NT Aboriginal communities provided one of the central justifications for the NT Intervention. However, this problem has not improved under the Intervention and there is evidence to suggest it has become worse.

The Office of the NT Children’s Commissioner conducted an analysis of hospitalisation figures relating to the NT in 2014. This demonstrated that the rate of hospitalisation for Indigenous women in the NT had increased 23% between 2008 – 2012 while the rate for non-Indigenous women in the NT remained steady. This makes Indigenous women 61 times more likely to be hospitalised for assault than non-Indigenous women in the NT.

The extreme rates of family violence in many NT Aboriginal communities provided one of the central justifications for the NT Intervention. Source: AAP

Aboriginal community controlled organisations and many other Aboriginal community leaders have insisted throughout the Intervention, that seriously addressing these problems requires respect for self-determination, and the urgent allocation of resources for community led development.