This story contains references to self-harm, medical procedures and distressing themes.

Ever since he was a teenager, Jay (not his real name) has been insecure about his height. In high school, he felt like he was treated differently because he was shorter than the other boys.

Now a young adult, Jay is considering getting cosmetic surgery to become taller.

He’s never been in a relationship – and hopes altering his height will change that.

“I was actually keen on it and I discussed it with my parents…they were actually pretty supportive about it,” Jay told The Feed.

He stumbled across the idea in online forums where people discussed limb lengthening surgery. They named doctors and listed prices. Users suggested flying to Türkiye, India or the US, where the procedure is commonly performed.

Leg lengthening surgery involves breaking the bone and inserting metal pins, then gradually stretching the limb out over months.

In Australia, leg lengthening surgery is mostly used for trauma cases, such as post-cancer reconstruction, and for people born with unequal leg lengths - not cosmetic purposes, according to the Australasian Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgeons (ASAPS).

If Jay goes ahead, the surgery will set him back $50,000 to $100,000. He’ll need to spend around three months recovering overseas before returning to Australia, and undergo a long, painful rehabilitation process to learn to walk again.

Jay said a full recovery could take years. The thought has given him some pause.

“I was just like, you shouldn't spend, like, 50 grand just to break your legs and not walk for a year,” Jay said.

“I'm still thinking about it, but I'm more focused on getting the money right now, not the surgery itself.”

Dr Naveen Somia, the former president of ASAPS, says choosing to have surgery overseas can be risky.

“Hospitals may not have the same stringent standards for quality of care, hygiene, and patient safety as here in Australia, increasing the risk of infection or complications," he said.

"In some cases, Australians undergoing surgery overseas have also found that they are victims of ‘surgery ghosting’, where their surgery is carried out by a different surgeon to whom they consulted, which is illegal and highly unethical in Australia."

What is looksmaxxing?

At its core, looksmaxxing (or looksmaxing) is simply any attempt to improve your physical appearance. It can be as simple as eating healthy or following a skincare routine.

But on the extreme end, it’s driven people to perform bizarre home cosmetic surgeries.

Looksmaxxing is now a trend that’s spread beyond small online forums to mainstream platforms like TikTok and Instagram, fuelled by fitness and wellness influencers. The term has its origins in the incel community: an online movement of involuntarily celibate men who believe women will never date them.

Jay, who identifies as an incel, is convinced women will only date the most good-looking men. Like most looksmaxxers, he believes facial features and height are the most important factors when it comes to male attractiveness.

“Height…gives you a more dominant halo. And facial appearance, people just are naturally attracted to that,” he said.

“So it not only helps you in dating, it helps you in making money and building relationships, building better friendships with other people.”

There is an amount of research that backs up the idea that looks can influence people’s judgements of us - one study by the Australian National University found taller men tend to be paid more than their shorter counterparts. Evolutionary psychologists have also found we tend to be more romantically attracted to people with attractive faces.

It’s a premise looksmaxxers have taken to heart. They discuss techniques such as plastic surgery, injecting anabolic steroids and mewing – the technique of keeping your tongue on the roof of your mouth, in hopes of changing your jawline.

Mewing tutorials are becoming popular on mainstream social media platforms like TikTok. Credit: TikTok

But this hyper-fixation on looks can sometimes become dangerous.

Danni Rowlands is the head of prevention at Australia’s eating disorders and body image issues charity,.

She said aesthetic trends like looksmaxxing are harmful and unhelpful.

“When there's a real focus on changing appearance, or when the end goal is that we're going to achieve an ideal and the suggestion is that that is going to make your life better, or that's going to make you more lovable, successful, attractive - we're really tightly connecting our weight and appearance to our worth,” she said.

“That’s a really dangerous thing for people to be striving for.”

Danni Rowlands says appearance-focused trends like looksmaxxing are harmful and unhelpful. Source: Supplied / Butterfly Foundation

Botched surgeries and regret: the dark side of looksmaxxing

In forums where users heavily critique each other’s appearance and egg each other to change their looks, some have taken drastic measures – with sometimes disastrous results.

One of the most popular looksmaxxing forums is filled with examples of home surgeries gone wrong.

This user said they were hospitalised after buying filler off the dark web and injecting it, using an unsterilised needle.

Plastic surgeon Dr Lily Vrtik warns doing DIY surgery at home comes with serious and often irreversible risks.

“If you do not have many years of training in facial anatomy, there is a risk of facial nerve injury, which could result in permanent paralysis of the facial muscles.”

Sarah Bonell is a former research fellow at the University of Melbourne who studies the popularisation of cosmetic surgery.

She said Gen Z and younger millennials are the first generation of heterosexual men to normalise getting cosmetic procedures.

“It’s become far more common for men to seek out cosmetic surgery, Botox, fillers, and even more ‘mundane’ appearance enhancements (e.g., getting facials, painting nails, wearing makeup).”

Thirteen per cent of all surgical cosmetic procedures in 2021 were performed on men, according to the International Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery.

Bonell said there’s a strong link between having an interest in cosmetic surgery and body dysmorphic disorder (BDD) – a mental illness that causes people to become preoccupied with a perceived flaw in their appearance.

“Cosmetic surgery marketing is very sneaky in its ability to inform populations of ‘deformities’ that need ‘fixing’ that in the past would’ve just been considered normal variations in human appearance…for men, height.”

One forum user, who had undergone extensive plastic surgery over 12 years, said they regretted their decision to go under the knife – and warned others not to follow in their footsteps.

“Anyone here like I was years ago thinking this will change your life and be some kind of sex god. FORGET IT!” the post reads.

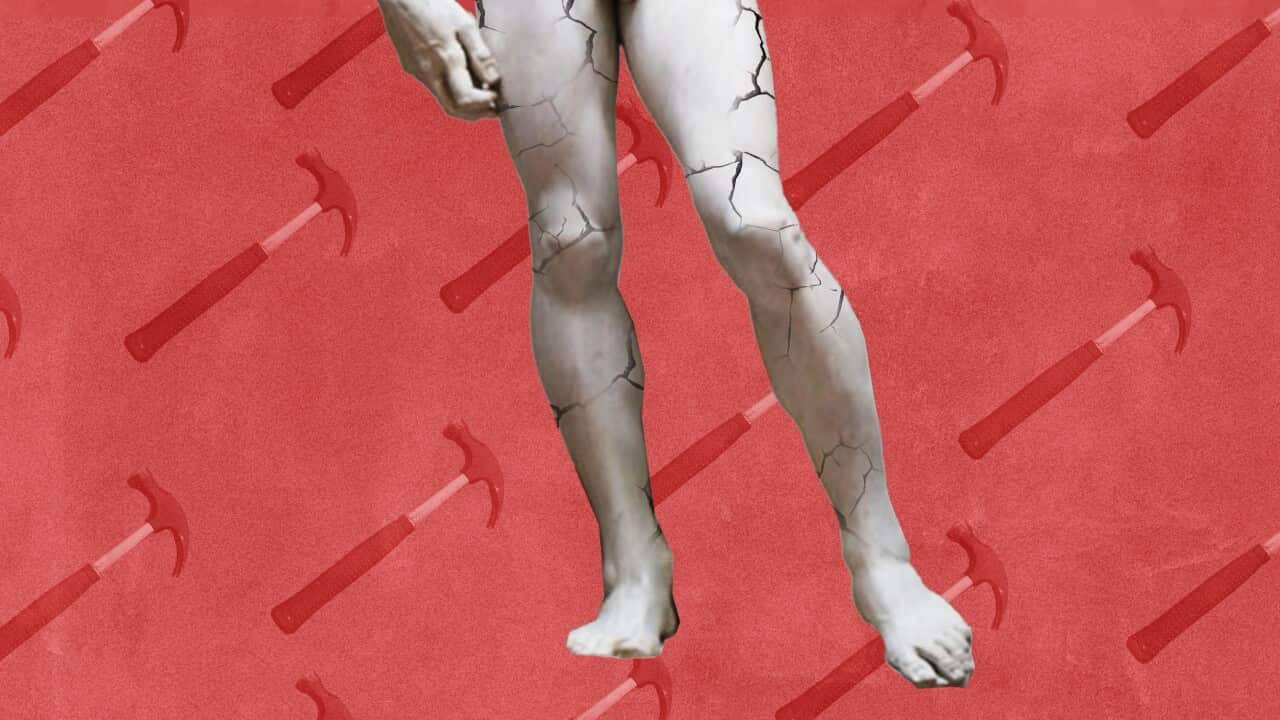

The troubling trend of bonesmashing

Bonesmashing is an unfounded technique practised by a small subset of the online looksmaxxing community.

It involves using a blunt object, to try to reshape the cheeks, jaw and other bones in the face for a chiselled look.

Bonesmashers often cite a theory that healthy bones will remodel themselves when under stress. But Vrtik said the practice is not backed up by science and can lead to serious facial injuries.

“A bone's response to repeated trauma is unpredictable and there are no studies to support that repeated trauma will achieve a chiselled appearance,” she said.

"Facial fractures can result in a whole array of issues. From damage of the brain, detachment of eyeball muscles and eyelid structures, collapse of nasal airways or the cheekbones, catastrophic haemorrhage, blindness, an inability to bite or chew, injuries to the ear canals and hearing, and more.”

Ryan (not his real name) identifies as an incel and has seen others in the community taking this extreme measure in an attempt to improve their facial features.

Ryan says he's heard of other incels hammering their jawlines to change their looks. Source: SBS

“It’s a really risky business…they're that desperate that they're doing stuff like that all the time.”

How many men experience body image issues?

Body dissatisfaction is growing among young men in Australia, research by the Butterfly Foundation shows.

A 2022 survey found one in five young males aged 12-18 experience body dissatisfaction. Over half desired to be taller, while over 65 per cent desired to be more muscular.

Rowlands said low self-esteem, social media and appearance-based bullying are some of the culprits feeding into body image concerns – which can lead to harmful behaviours like under-eating or over-training, and feelings of shame and embarrassment.

She said looksmaxxing is preying on people’s insecurities around their bodies.

“We've had these conversations around female bodies for many, many years around objectification and how that's a really harmful thing.

“Looksmaxxing is also doing the same thing for men. We're objectifying the male form…and therefore we're…not seeing people as a whole.”

Rowlands urges those who are concerned about their body image to talk to a friend or partner, or consider getting professional support.

She also suggests people make sure they’re consuming a wide variety of content online.

“It’s really important to try to diversify your feed, make sure that you try to challenge those algorithms so that you can see content that is broader than this,” she said.

“The more we see, the more we want to probably achieve that [idealised body].”

*Names have been changed.

The Feed spent months investigating Australia’s incel community. Watch the full documentary on.

- Additional reporting by Michelle Elias

Readers seeking support for body image concerns and eating disorders can contact Butterfly Foundation on 1800 33 4673. More information is available at

MensLine Australia offers 24/7 support for men of all ages in Australia. Contact MensLine on 1300 78 99 78. More information is available at

Readers seeking crisis support can contact Lifeline on 13 11 14, the Suicide Call Back Service on 1300 659 467 and Kids Helpline on 1800 55 1800 (for young people aged up to 25). More information and support with mental health is available at and on 1300 22 4636.

supports people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds.