TRANSCRIPT

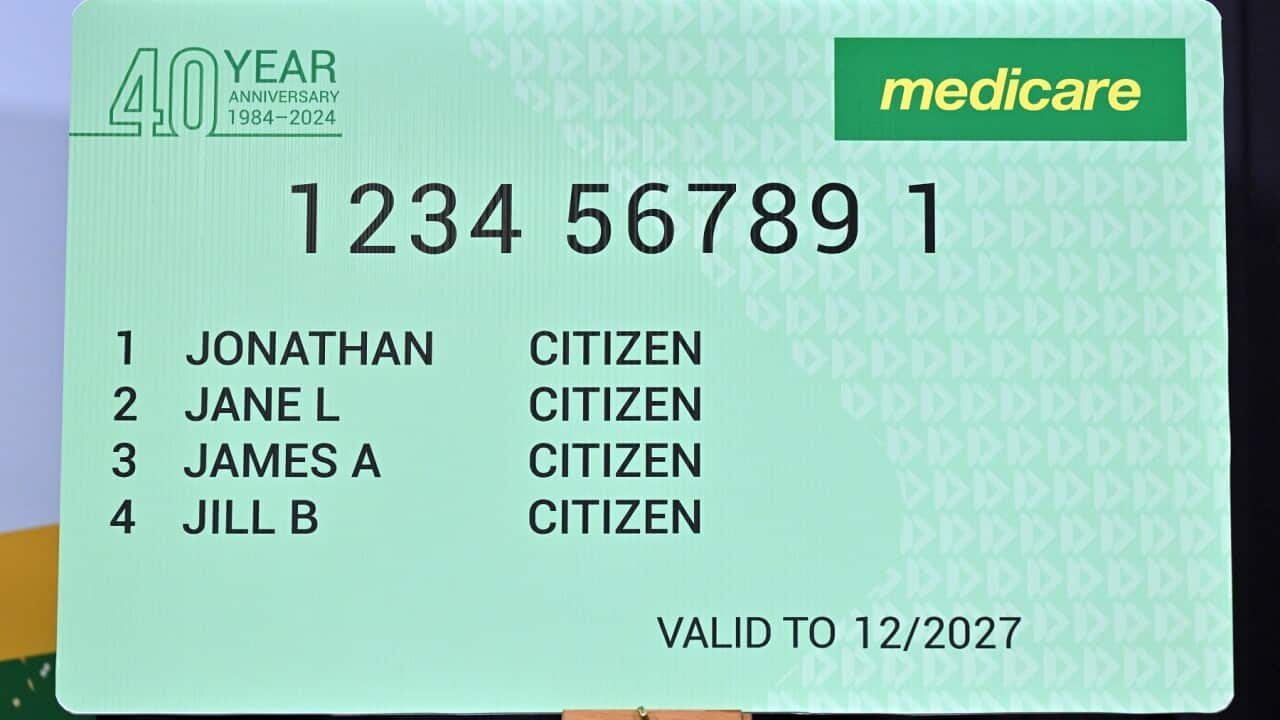

Medicare is turning 40 this year, and to celebrate, the government has launched a special commemorative card.

But do you know how that little green card actually works?

A growing number of experts is urging the government to go much further than a special card.

Peak bodies representing healthcare consumers and medical professionals say the government should fund a public education program about Australia's healthcare system.

Dr Elizabeth Deveny is Chief Executive Officer of Consumers Health Forum of Australia, or C-H-F.

"The healthcare system is critical to all Australians. We pay for it. Through our taxes, or our Medicare levy, or our private health insurance, or our out-of-pockets, or through buying our medicines, or through the petrol it takes to get to the appointments or the time we take off work. It's our health and we have a right to understand what our tax dollar is buying, and how we can best use it."

When Medicare was first rolled out forty years ago, Dr Deveny says there was public discussion about how the new universal healthcare system worked.

"It was in the papers, people understood what its intent was, and how they might access it. And indeed, when Medicare first came in, the government funded people whose job it was to go out into communities and be available to explain it to you: 'Hey we've got this new thing called Medicare, this is how it works, you're going to get a card, this is how you use it, this is what it pays for.'"

But she says younger people and those who arrived in Australia after 1984 missed out on that education.

"So, they just grow up with Medicare and the thing is, no one teaches you how it works. We don't teach it in schools. Indeed, even clinicians say that when they finish their training and start working they discover there are things about Medicare that they didn't understand."

C-H-F is concerned that Australians' gaps in knowledge about the health system mean people are missing out and paying more for healthcare.

Their concerns are echoed by the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners, which has issued a statement calling for greater health literacy - specifically about Medicare.

Both organisations argue that in a cost-of-living crisis, it's more important than ever for Australians to know they are entitled to free and subsidised healthcare.

Last year, the proportion of people who delayed or did not see a G-P because of the cost rose to 30 per cent [[30.3]], according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics.

Worryingly, those with a long-term health condition were more likely than others to skip their visit.

Dr Deveny says it's those people who may actually benefit the most from greater education.

"In the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme we have this thing called a safety net; we have it in Medicare too. When you've spent a certain amount of money in Medicare the government tells you you've spent a certain amount of money, things will be cheaper for you now. And when you get your medicines, the same sort of scheme applies, so we have a safety net for your government-funded medicines. But when you hit the limit, nobody tells you. So, we're pretty confident that there are a lot of Australians who have chronic disease, who've spent a lot of money on medicines who don't realise that they've passed the threshold the cost of their medicines should've been reduced or indeed free."

C-F-H would like to see complicated rebate processes like this automated and made more flexible for individuals.

But Dr Deveny stresses that simple fixes often come down to education.

For example, she says many people don't know they can ask their GP for bulkbilling even if it's not the practice's normal procedure.

Even if the doctor can't offer a totally rebated service, they will link the patient with other services that can.

Dr Devaki Monani is Senior Lecturer in Social Work at Charles Darwin University.

She says education programs will also need to take into account migrants' political and cultural context, not only in their previous countries but in Australia too.

"There is some sort of a challenge when we put in all culturally and linguistically diverse communities, or when we blanket a statement saying 'migrants'. The issue is that Medicare eligibility is actually dependent on your visa status."

Dr Monani says language also can be a major issue in healthcare settings and in communicating public health messages.

But she points out it's not just about the words used, it's also about offering a conceptual framework.

"One of the easiest languages to translate in any cultural or political context is the "rights" language, to say, our rights are universal, particularly if we're in a democracy like Australia. And so this reminder constantly that as a migrant you're now settled in a democratic, rights-based welfare system. And I think that's not communicated effectively. Migrants kind of feel... they kind of live in fear, and particularly those that are temporary migrants."

Dr Monani says that fear can translate into mistrust of institutions like the healthcare system, or an unwillingness to claim benefits.

"We need to remind migrants - and other non-migrants groups in Australia - that Medicare is a basic human right. And we're really lucky to have that health platform in Australia and have health accessibility. So, we must fight really hard and we must keep communicating to migrants that Medicare is your basic human right and you need to access it as much as possible."

For Dr Deveny, it's also a right to education.

“There are better ways for people to find out about about how Medicare works rather than by word of mouth or personal experience. So in our budget submission we're arguing people should be given the opportunity to learn about Medicare and that we would be able to do that for them by providing them with resources in various languages, through community access so that they can better understand how to make this work for them."

In fact, the story of SBS itself is entwined in the effort to communicate public health messages to people who spoke languages other than English at home.

It was launched by the Whitlam government in 1975, the same year it rolled out Medibank - the precursor to Medicare - with the explicit aim to communicate information about the new national healthcare system.

On 45th birthday of SBS in 2020, former managing director Michael Ebeid reflected on the broadcaster's role.

"I think it was a really good policy decision by the then government to set this up to help unite migrants in Australia and to help people understand what it is to be Australian and the fabric of Australia. So I think our role is more important today than ever in the history of Australia."