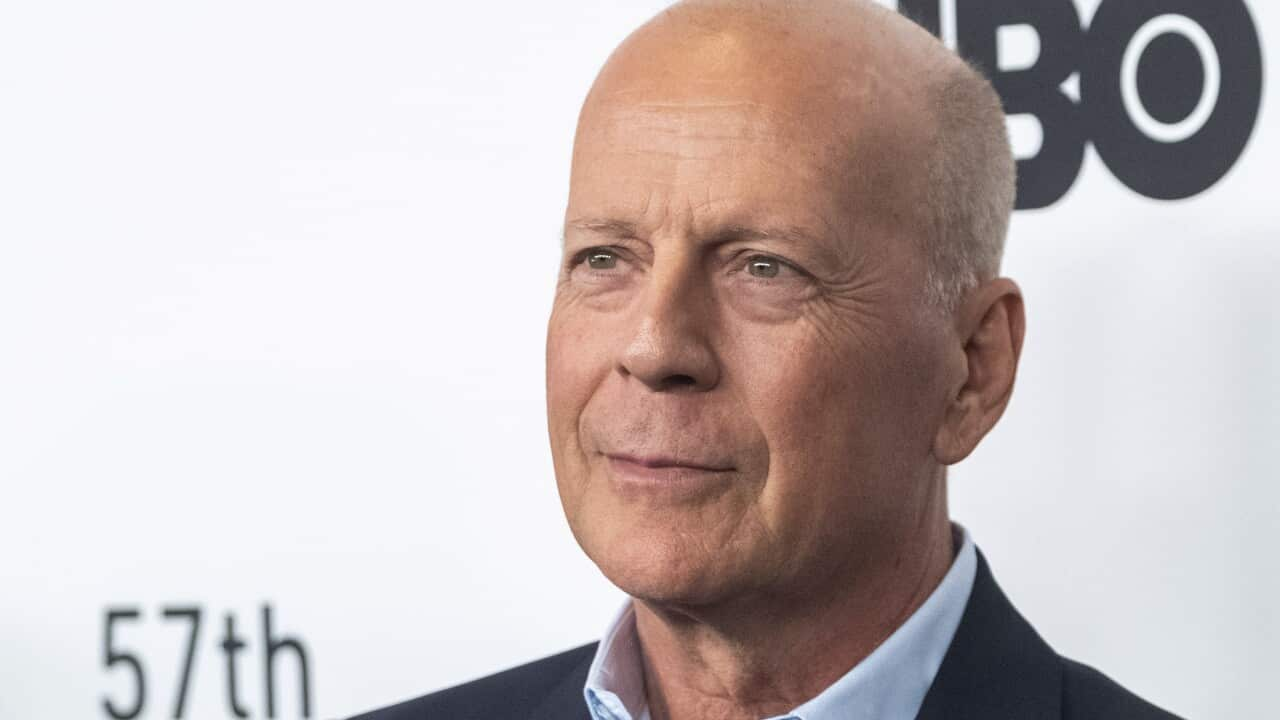

Ten months after announcing he had aphasia, Bruce Wills’ family has made a public statement sharing his new diagnosis of frontotemporal dementia.

The 67-year-old’s family said his symptoms have progressed and that his “challenges with communication are just one symptom of the disease Bruce faces”.

According to , Frontotemporal dementia is “progressive and affects everyone differently. This means that symptoms may be mild but will worsen over time.”

The condition occurs when one or both the frontal or temporal lobes of the brain become damaged. There are four different types of this dementia, each with its own signs and symptoms that may include language impairment.

Frontotemporal dementia is more commonly diagnosed in people under 65 and there are no known treatments to cure or slow frontotemporal dementia.

“As Bruce’s condition advances, we hope that any media attention can be focused on shining a light on this disease that needs far more awareness and research,” the family said in a statement.

In 2022, Hollywood star Bruce Willis, shocked the entertainment world after he announced he was retiring after developing a cognitive condition called aphasia.

The disorder affects parts of the brain that command language and communication, and can leave the patient with difficulties talking, listening, reading and writing.

It occurs in one in every three strokes, and can also be caused by brain injury, dementia, or in people with epilepsy. For most people the onset is sudden, but it can also develop gradually from a slow-growing brain tumour or a disease that causes progressive damage.

It’s estimated at least 140,000 Australians who’ve suffered strokes are living with aphasia.

The Los Angeles Times reported questions had been raised about Willis’s short-term memory in the past couple of years leading up to his diagnosis, and his family said he had experienced some “health issues”.

“Bruce is stepping away from the career that has meant so much to him,” his partner Emma Heming Willis wrote on Instagram. “We are moving through this as a strong family unit… as Bruce always says, ‘Live it up’, and together we plan to do just that.”

What is aphasia?

Aphasia is not a disease, rather a symptom of damage to the left hemisphere of the brain.

The brain injury, whether it be stroke, head injury, brain tumour, infection or dementia, leaves parts of the brain involved in speech and language damaged.

The symptoms can include: difficulty conveying thoughts through speech and writing, difficulty understanding spoken or written language, difficulty recalling names of objects, people and places, or difficulty using numbers and gestures.

But the symptoms vary greatly from person to person. Some people with aphasia recover from the condition naturally over a period of time. Others can have difficulties with one of the aspects of communication, or with all of them.

Emeritus Professor Linda Worrall, from the School of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences at the University of Queensland, says the severing of understanding and communicating language can be devastating.

“Think about it, what have you done today that involves communication? Waking up to the news, understanding the news, maybe going on your phone, texting a friend, having conversations with your partner, and even reading road signs as you drive to work. It affects pretty much every part of people’s lives,” she said.

“Especially work. A quarter of stroke patients are of working age, and people with aphasia rarely return to work. Most work situations involve some sort of language or communication.”

Professor Worrall says common misconceptions around people with aphasia is that they’re not intelligent, or not competent to make their own decisions.

“It’s just the language that has been affected, but there is a bit of stigma to anything that goes wrong with your brain.”

Bruce's story

Bruce Aisthorpe developed aphasia after suffering a stroke in 2011.

“It happened on the weekend. [My wife found me] walking up and walking down to the bottom of the stairs, but [when I tried to speak] no words were possible, nothing came out,” he said.

Bruce recovered in hospital overseas, where doctors discovered he had developed aphasia. He struggled to understand things being said to him, he had lost much of his vocabulary, and he had trouble reading.

Soon afterwards, he flew home to Brisbane for a heart operation for his carditis, and then started rehabilitation, including speech therapy. .

“The first four months, four days a week, I had occupational therapy, physiotherapy and speech therapy. Before the speech therapy I had no words, only cat, dog, things like that,” he said.

He was unable to work after his stroke. “I couldn’t work, I had no words. My career ended. But I was very lucky with my income protection insurance.”

READ MORE

SBS Insight: Strokes

Treatments

Australians with aphasia are provided support under the NDIS based on the level of their disability from the condition. Bruce receives funding for three hours of speech therapy a week, and is also supported by apps designed to develop language and communication skills.

But the NDIS support was not available when Bruce was first diagnosed with aphasia in 2011. After the first four months, Bruce shopped around to see what treatments were available. He turned to private speech therapy to improve his communication skills, and even spent $35,000 to travel to the Rehabilitation Institute of Chicago (now called the Shirley Ryan AbilityLab) in the United States for an intensive speech therapy program.

He soon met Professor Worrall, who was working on an Australian-based version of the intensive speech therapy program along with Professor David Copland, called the Comprehensive High-Dose Aphasia Treatment, or CHAT, under the University of Queensland’s Queensland Aphasia Research Centre (QARC).

The program offers an intensive course of speech therapy that runs for three hours a day, three days a week, for eight weeks, compared with the three hours a week model of the NDIS. The program also encourages small group discussions between people with aphasia, who all participate in the program at the same time.

Professor Copland said the CHAT program is still in the trial stage, and researchers from QARC have been evaluating the effectiveness of the program.

“60 per cent of people with aphasia, 12 months after a stroke, will still be suffering from those symptoms, so it requires a lot of [speech therapy] work,” he said. “We’re trying to identify what’s the best package that we can have.”

“It’s highly tailored to each person, they set goals at the beginning. One of Bruce’s goals was to read Lauren, his daughter, a bedtime story,” Professor Worrall said.

“So we worked hard on Bruce’s reading. And Bruce’s wife Tash came into the program, and she learned how to communicate with people with aphasia.”

Bruce Aisthrope with his wife Tash and daughter Lauren celebrating his son Cameron's fourth birthday.

Living with aphasia

Professor Copland said people who develop aphasia after a stroke are four times more likely to have depression than the general population.

“It can lead to social isolation. It really has effects on quality of life, affecting returning to work or returning to all the activities that people get enjoyment and satisfaction out of,” he said.

Professor Worrall said Bruce was remarkably resilient about his condition.

“Bruce is pretty amazing really. He has sought out therapy but he has not been too emotionally affected by the aphasia,” she said.

“I’m lucky, I didn’t have any sort of paralysis [after my stroke]. The body is OK, it’s just the talking. It’s been hard going, but I’ve made big gains,” Bruce said.

Bruce has since joined the Australian Aphasia Association as a board member, to help raise awareness of his condition and treatment options.

“I’m lucky, I didn’t have any sort of paralysis [after my stroke]. The body is OK, it’s just the talking. It’s been hard going, but I’ve made big gains,” he said.

“I’m not worried about the past. I’m just looking towards the future now.”