Watch Insight's double episode on Seeking Justice — and what it looks like for different people — on

In 1997 Terry Irving walked out of Townsville’s Stuart Prison after the High Court quashed his wrongful conviction for an armed robbery committed nearly five years earlier.

Other inmates remarked that he didn’t look particularly overjoyed as he left, but Terry felt let down by a system that was supposed to protect him.

After years behind bars, justice for him meant compensation and an apology from the Queensland government.

He couldn't have known it back then, but 26 years later he'd still be waiting.

Wrongfully convicted for armed robbery

Terry is a Gadigal man who grew up in Sydney before moving to Cairns. He was a regular pool player at his local pub, and it was there in 1993 that a man approached him for a favour.

“This guy asked me if he could borrow my car to run an errand. It was an old car, and I agreed and I lent him my keys,” Terry told Insight.

A few hours later, the man returned with Terry’s car. Later that evening as Terry drove home, he heard a radio news report describing a bank hold-up in Cairns, which included details of the car and suspect.

While the description of the car didn't match his own and that of the offender didn't match the person he'd lent the car to, the reported registration number belonged to his car.

“I assumed that maybe there was a mistake," he said.

He heard nothing further until around two months later when police turned up at his work.

Terry was arrested, charged in connection to the robbery, held on remand and later charged with armed robbery.

Later that year, Terry was convicted in a Cairns courthouse by a jury and sentenced to eight years in prison with no prospect of parole. His lawyer had pulled out of his trial at the last minute and sent a colleague to cover for him.

“It was debilitating,” Terry told Insight.

Life in jail

In prison, Terry took up a job in the library, determined to get access to law books to help clear his name.

“If it took every day of those eight years, I would not stop trying to prove my innocence," he said.

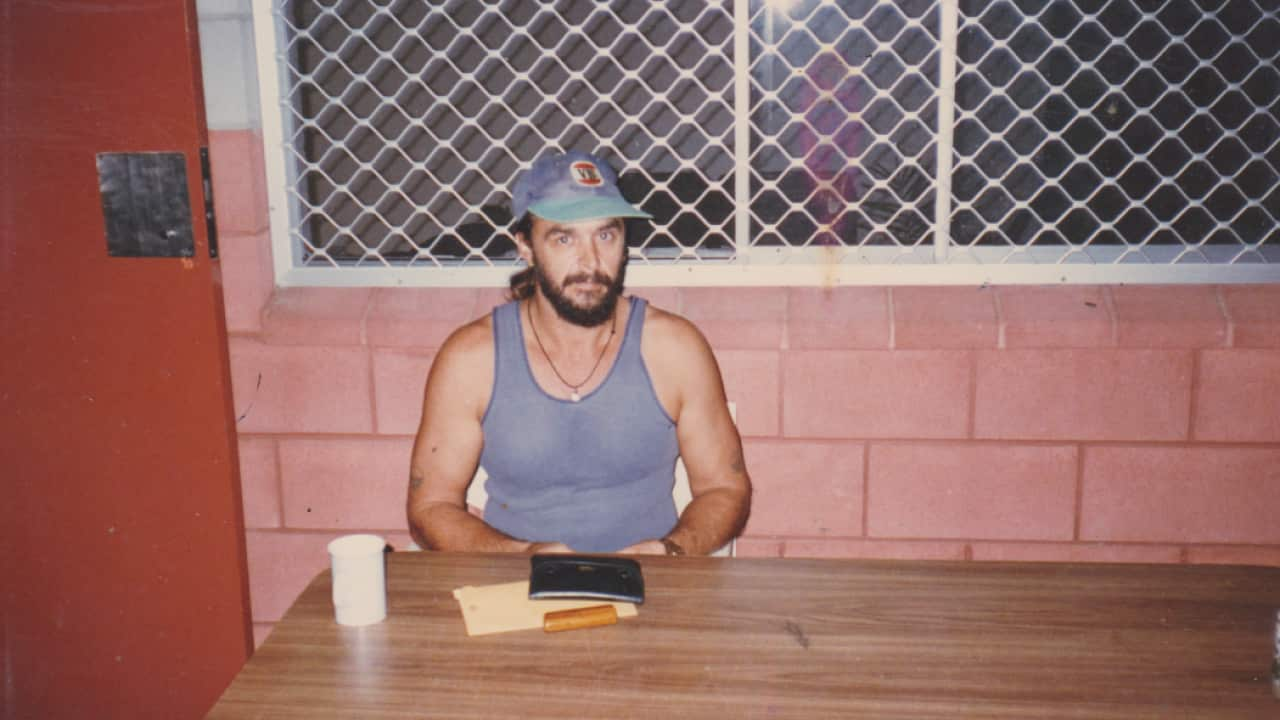

Terry Irving in 1994 at Stuart Prison, now known as Townsville Correctional Centre. Source: Supplied

“I failed to understand the complexities of the court," Terry said.

He had been knocked back a number of times by Queensland legal aid, so when Michael O’Keeffe – a solicitor who had just arrived in Townsville to take charge of the Legal Aid Office – showed up at Terry’s prison, he “copped it a bit” when he bumped into Terry.

“After we calmed down a little, he asked me if he could see me again,” Michael told Insight.

“I said, I'll come back in a week, and we'll sit down and talk about it? And we did.”

'This guy's been railroaded'

Michael was immediately alarmed by the inconsistencies in Terry’s case and evidence used by police to convict him.

The description of the offender didn’t match up with Terry’s appearance; eyewitness accounts that identified Terry as the robber were hesitant when identifying him; and other witnesses who said they couldn’t identify the robber didn’t have statements recorded by police.

“There were some substantial differences between what the police were saying the witnesses said, and what in fact, ended up being what we found out that witnesses actually said,” Michael said.

“I thought, well, if this is true, this guy's been railroaded.”

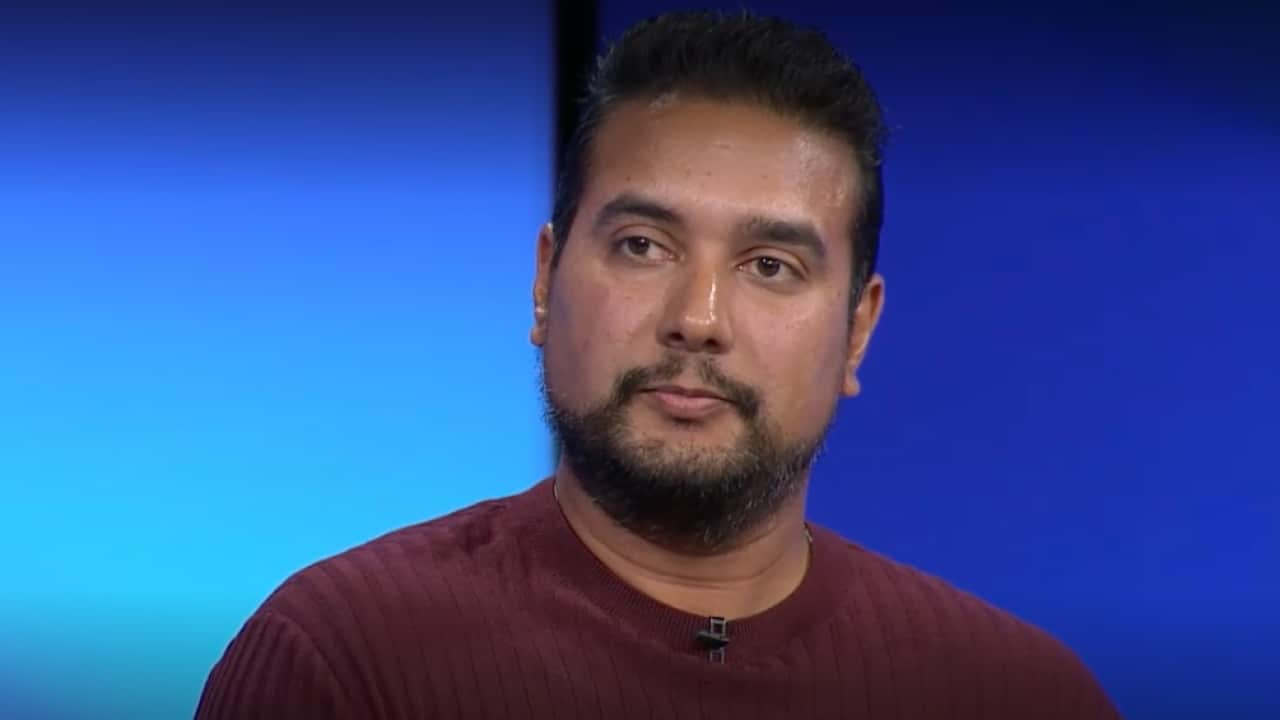

Lawyer Michael O'Keeffe (right) met Terry Irwing (left) when Terry was an inmate at Stuart Prison, now Townsville Correctional Centre. He was immediately struck by the inconsistencies in Terry’s case. Source: Supplied

The High Court Chief Justice noted that Terry's prosecution was “a very disturbing situation”, and that “the High Court had the gravest misgivings about the circumstances of this case”.

The fight for justice

Over the years that followed, Michael continued to fight for compensation and an apology for Terry until he retired and handed the case over.

The pair have also become close friends, with Michael the best man at Terry's wedding.

But without the apology and compensation, Terry feels he has never achieved justice.

It's like trying to climb Mount Everest backwards, with bare feet.Michael O'Keeffe

“We've been to the High Court three times. We've been to the Supreme Court at least twice. We've been to the United Nations Human Rights Tribunal. All of these agencies and courts, they're the highest in Australia and the highest in the world. They've all found in Terry's favour,” Michael said.

The United Nations Human Rights Committee in 2002 stated that Terry was “subject to manifest injustice” and “should be entitled to compensation”, and in 2021 the Queensland Court of Appeal ordered that Terry be paid damages.

Until he retired, Michael O'Keeffe (left) fought for compensation and an apology as a pro bono lawyer for Terry Irving (right) after his wrongful conviction. Source: Supplied

“Will we ever see the money in our lifetimes?” [Terry’s] life expectancy as an Indigenous Australian expires in two years, statistically," Michael said.

“It's like trying to climb Mount Everest backwards, with bare feet.”

No guarantee of compensation in Australia

Australia is the only democracy in the world that doesn’t have to by law offer compensation for those who've been wrongly convicted – a choice that has repeatedly been singled out by the UN.

Sometimes the state may offer an ex gratia payment, which is a gift arising from moral obligation rather than a legal requirement.

Other cases of wrongful conviction in Queensland – many of which were also against Indigenous men – have already had compensation rejected.

A spokesperson for the Queensland Department of Justice and Attorney-General told Insight her state wasn't unique in its conduct.

"No Australian state or territory has enacted a statutory mechanism or scheme for compensating people found to have been wrongfully convicted or imprisoned, with the exception of the ACT," the spokesperson said in a statement.

"Currently individuals who have been wrongfully convicted do have the opportunity to seek an ex gratia payment from the Queensland government, at the discretion of the attorney-general."

The spokesperson did not respond to Insight’s questions asking if Terry Irving was likely to see compensation in his lifetime, or if the government had any intentions to sign the relevant UN treaty mandating compensation.

It's uncertain iffor murdering her four children, will ever receive compensation.

While she was pardoned this year, her conviction remains. She will have to go to the court of criminal appeal to have it quashed and only then may she sue for compensation, which may or may not be granted.

His own form of justice

Memories of the years between 1993 and 1997 remain painful for Terry, who says he can't "erase or fill that gap within me or my sons".

"I have a void in our relationship that can never be bridged."

Despite this, Terry has been able to make some peace with the fact that he may never see any justice in the form of compensation or an apology.

For him, justice also comes in a different shape.

“I think that the journey has been illustrating how difficult it is to right a wrong.”

“And if I can shorten the path for someone else and their families, I've succeeded.”