By Rhiona-Jade Armont

WARNING

This piece includes images of deceased people

and contains content that may distress.

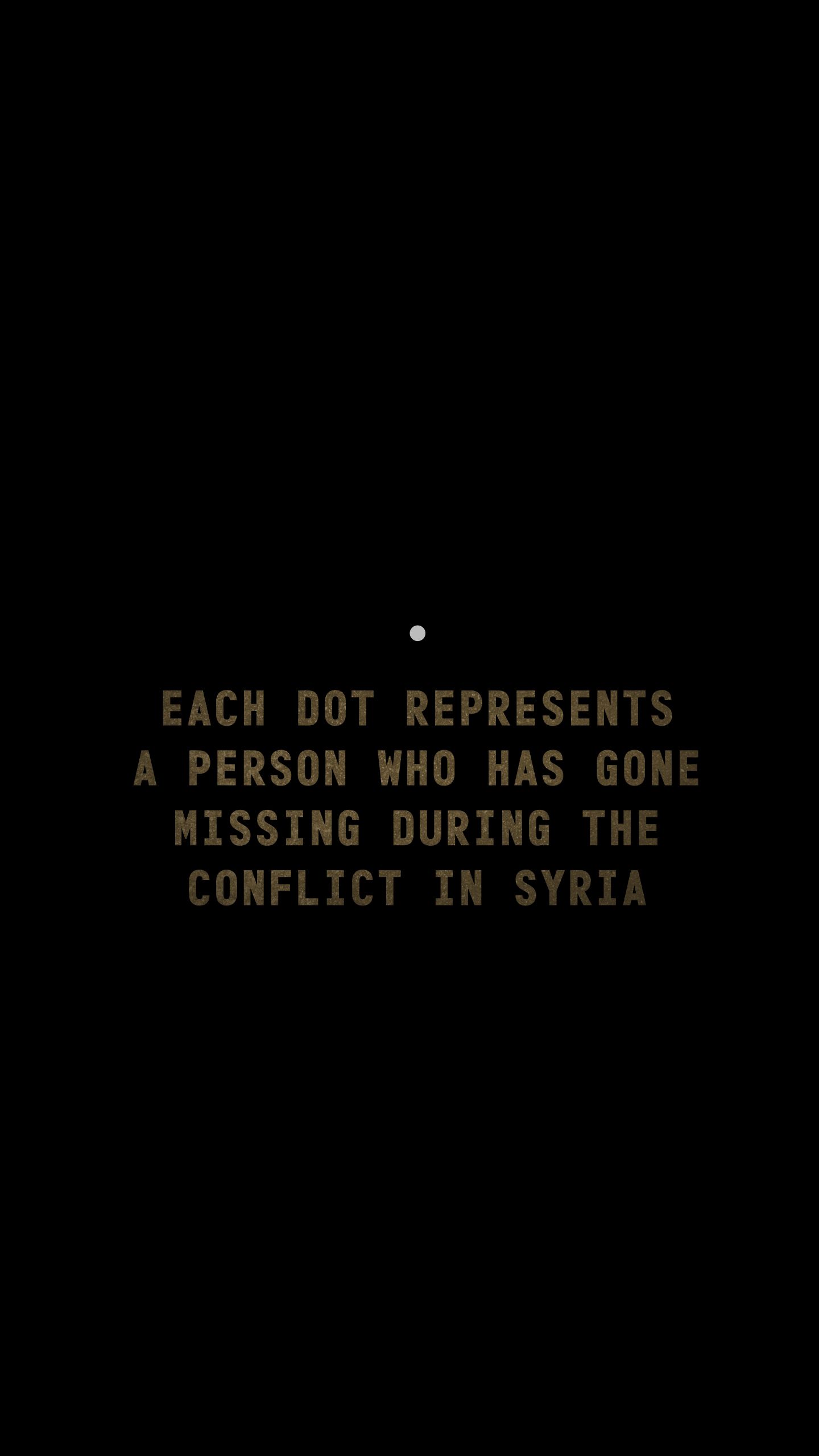

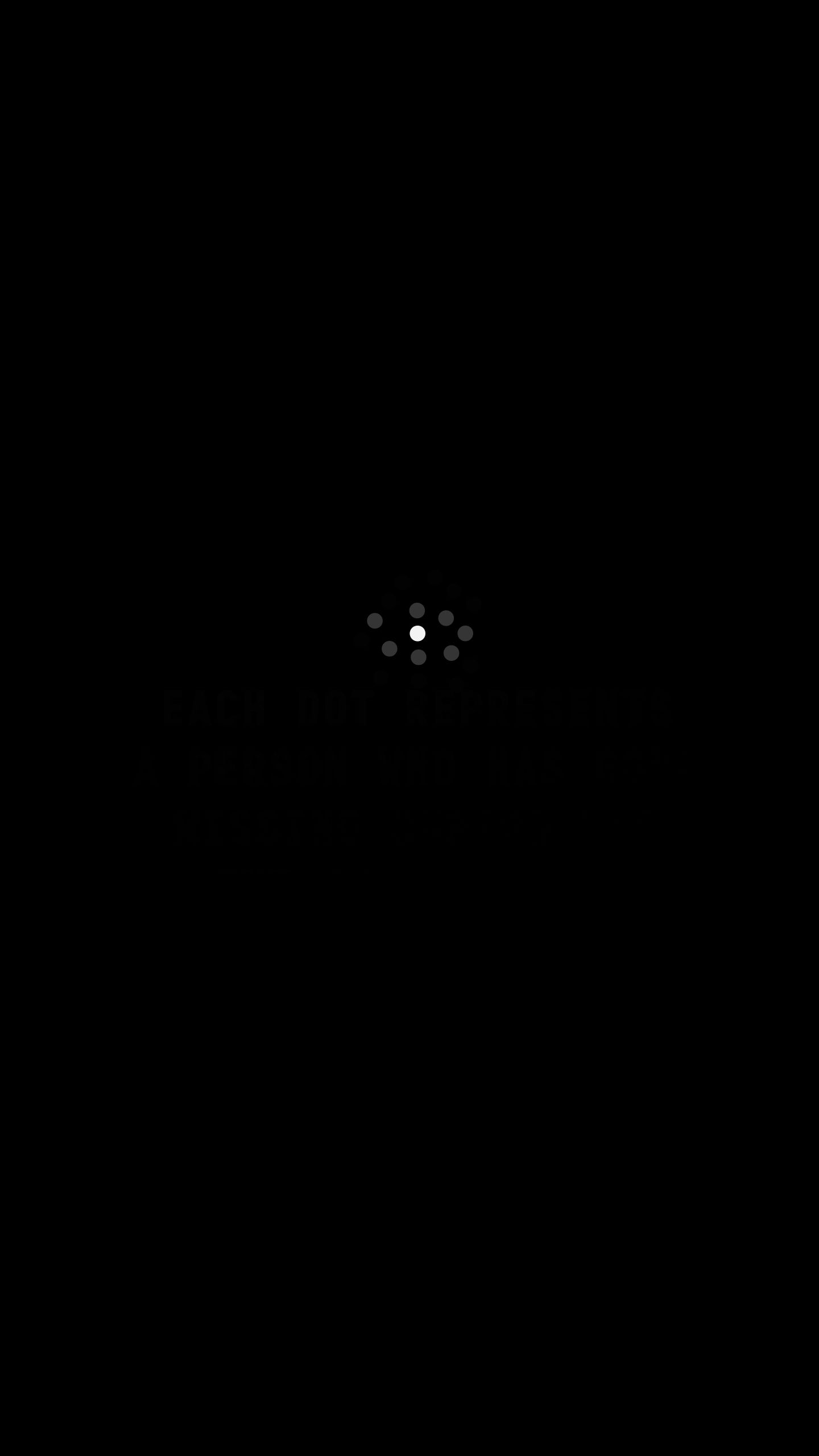

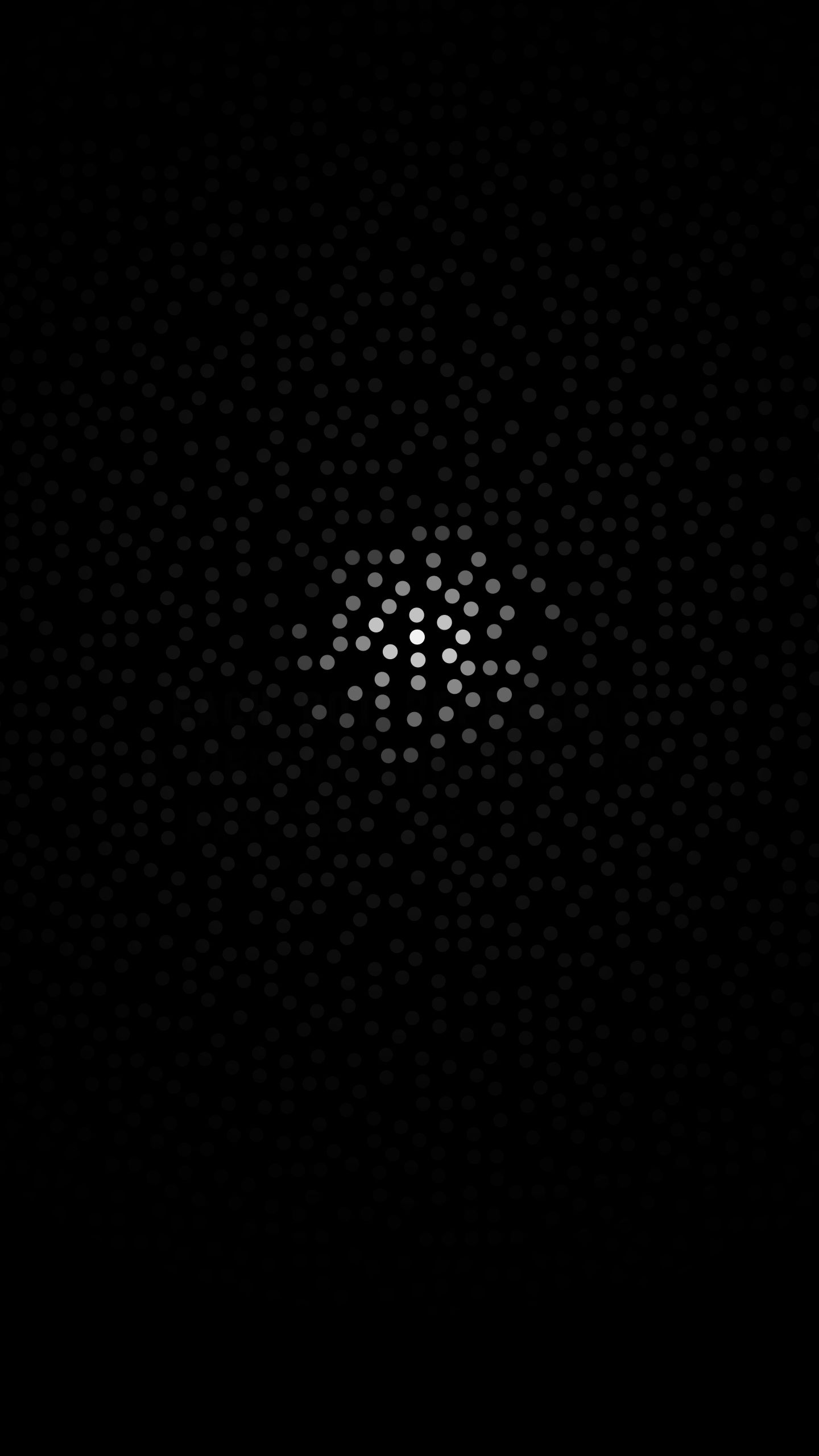

More than 100,000 people have disappeared since Syria's civil war began.

That's roughly four times the amount of Syrians living in Australia -- vanished without a trace.

SBS Dateline meets the people still searching for their loved ones and demanding accountability.

Believed to have originated in the city of Damascus, the Damask rose has long been associated with Syrian identity.

For some, the rose holds even greater significance: a symbol of the human soul itself.

Growing up in the northeastern city of Deir Ezzor, Yasmen Almashan and her six brothers lived a peaceful life.

They would play card games together and make figurines out of mud, acting out made-up stories.

“We once made flying ships for space invaders,” Yasmen says. “Like what we’d seen in science fiction movies.”

Yasmen recalls her home town being deeply conservative but says her brothers were always challenging tradition.

“They spoiled me a lot,” she says. “I was given a lot of freedom.”

“Few girls in the Middle East have what I had, to be honest.”

When Yasmen had finished her high school exams, her brothers were so proud that they took her out for dinner.

“This was a rare thing in my city - for brothers to organise a luxurious dinner for their sister in a restaurant.”

For Yasmen, these moments were filled with “unimaginable love”.

But as war broke out, the unimagined inched closer.

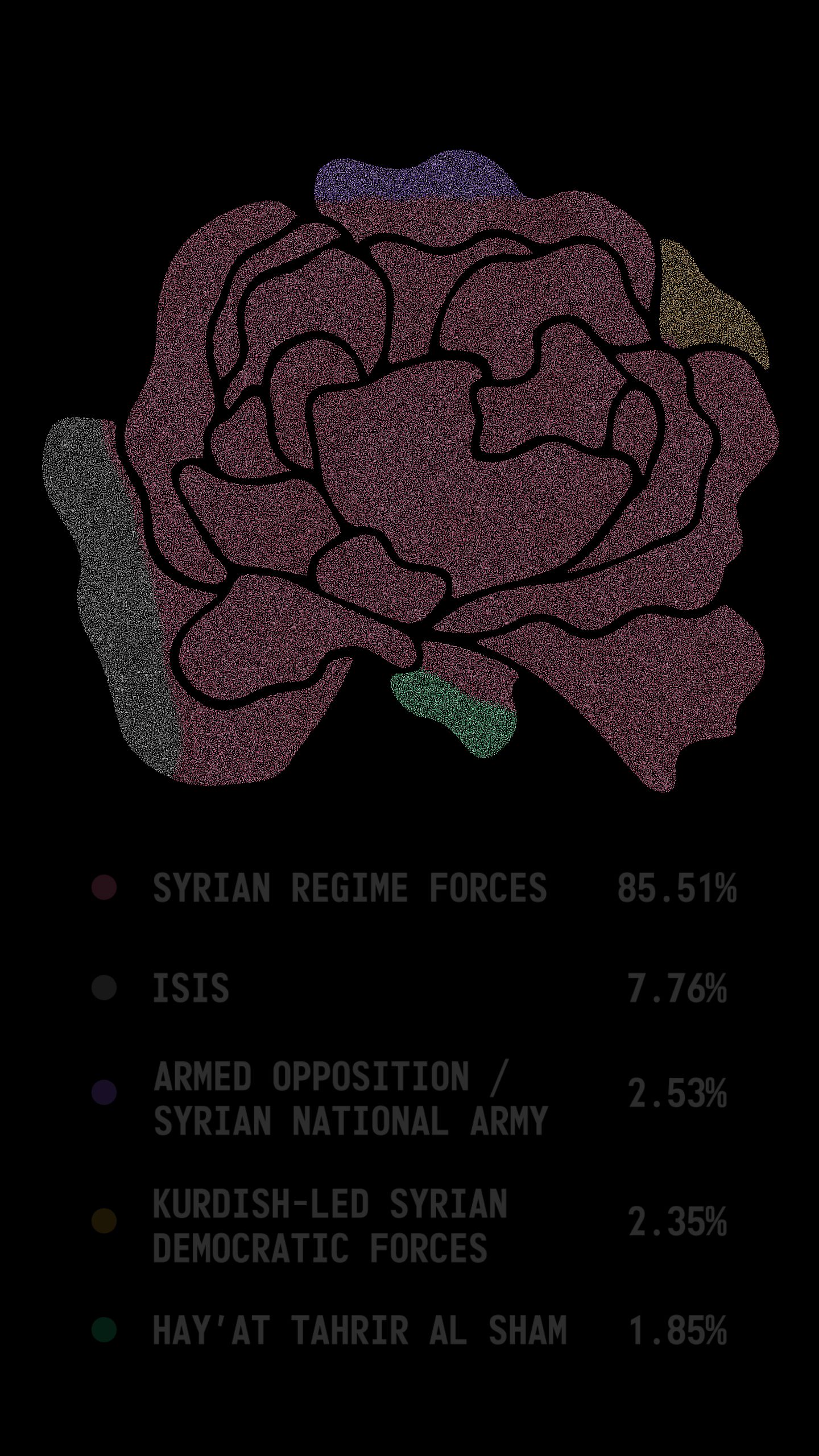

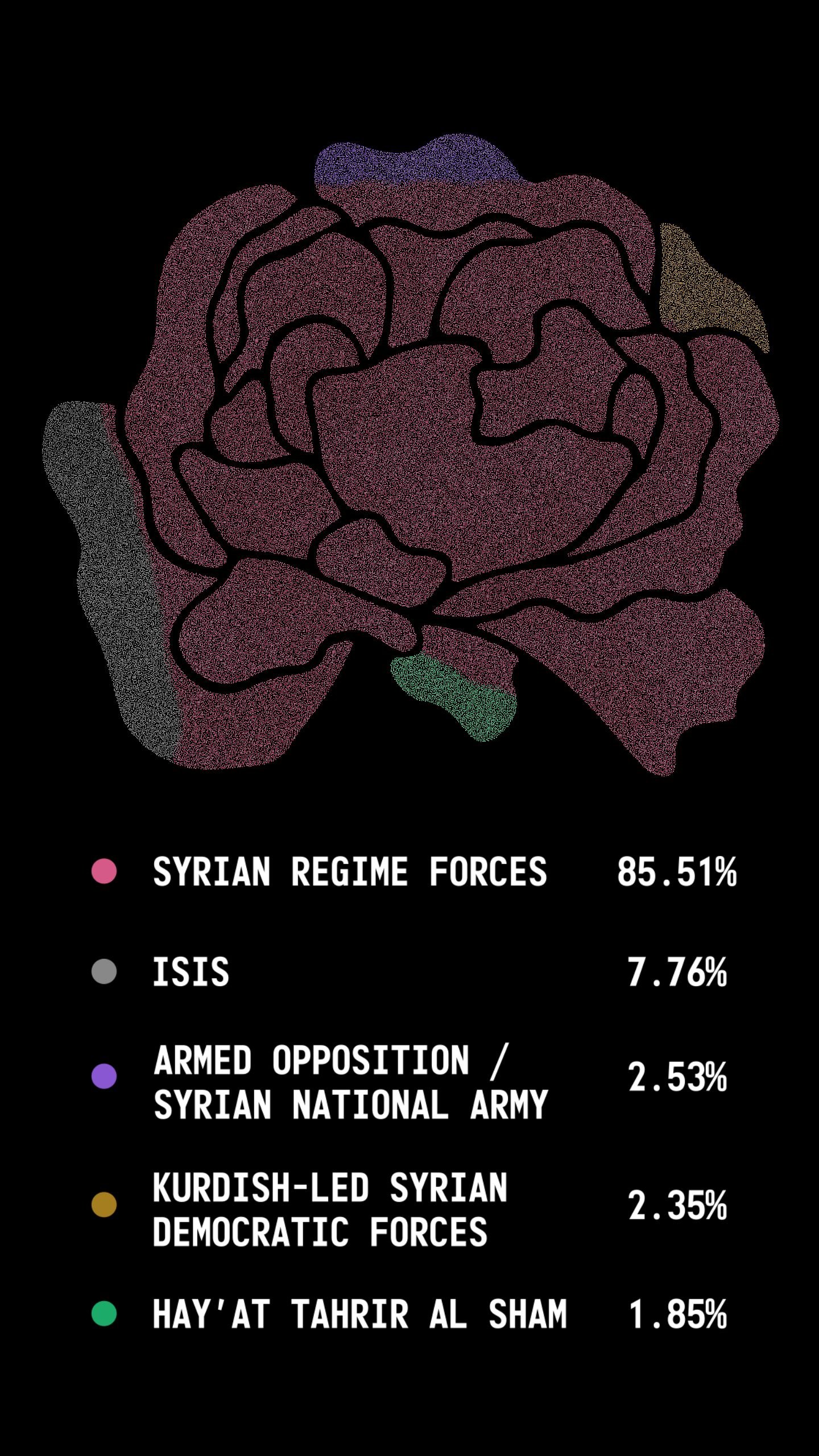

Twelve years after pro-democracy protesters first rallied against the regime of Bashar al-Assad, Syria is a fractured and volatile state.

Bashar al-Assad was re-elected as Syria's president in 2022, gaining over 95% of the vote. It's estimated eight million people, mostly displaced, refrained from casting votes. US and European authorities questioned the legitimacy of the result, claiming it violated UN resolutions in place to resolve the conflict, and no international monitoring taking place.

Since 2011, the country has seen the rise of various rebel groups, revived extremist outposts, and foreign forces reeled into a complex proxy war.

Amidst their competing interests, areas of control shifted constantly.

The battle for control crippled the country’s institutions and displaced nearly 13 million people, making it the largest refugee crisis of our time.

The war also claimed hundreds of thousands of lives, tearing families apart.

Amidst the chaos and carnage, Yasmen lost five of her six brothers.

“Losing them wasn’t a simple or easy loss,” she says.

“It is not normal to lose three quarters of your family in the blink of an eye.”

ZOUHAIR, 19

Zouhair was killed by a sniper during a protest in early 2012.

OQBA, 36

Two months later, Oqba disappeared.

OBAIDA, 26

Obaida was gunned down a few months later, while working as a medic helping those trapped beneath rubble.

TISHREEN, 40

Tishreen was shot not long after, while he was at home.

BASHAR, 19

Her youngest brother, Bashar, was then kidnapped by self-proclaimed Islamic State group (IS). He has been missing ever since.

In the recent earthquake, Yasmen also lost her cousin and their family of five children.

She has been shaken by violence and loss at every turn.

But it was Oqba’s disappearance, and the uncertainty of his fate, that weighed most heavily on her.

ZOUHAIR, 19

Zouhair was killed by a sniper during a protest in early 2012.

OQBA, 36

Two months later, Oqba disappeared.

OBAIDA, 26

Obaida was gunned down a few months later, while working as a medic helping those trapped beneath rubble.

TISHREEN, 40

Tishreen was shot not long after, while he was at home.

BASHAR, 19

Her youngest brother, Bashar, was then kidnapped by self-proclaimed Islamic State group (IS). He has been missing ever since.

In the recent earthquake, Yasmen also lost her cousin and their family of five children.

She has been shaken by violence and loss at every turn.

But it was Oqba’s disappearance, and the uncertainty of his fate, that weighed most heavily on her.

Enforced disappearance is an international crime.

It is typically characterised by three key elements:

- Depriving someone of their liberty

- Involvement of government officials

- Concealment of the victim’s fate

In Syria, families seeking information about their loved ones often describe deliberate deflection by authorities and sometimes, as in Yasmen’s case, intimidation tactics.

“We were always either faced by threats or someone warning us to stop asking about him,” she says.

It’s the combination of these elements that make a disappearance particularly distressing to both the victim and those searching for them. Because of this, disappearance is often described as having a “double paralysis” effect.

Victims like Oqba who are disappeared from the protection of the law are often subjected to humiliation and torture.

At the other end, their families wait for news that may never come.

Enforced disappearances are not anomalies.

They are frequently used in conflicts to systematically sow fear, suppress political dissent, and destabilise communities.

According to the latest report by the Syrian Network for Human Rights, 137 people, including six children and three women, were arbitrarily arrested or disappeared in February alone.

The majority of disappearances that continue to this day are carried out by the regime.

Cumulative number of people disappeared by the regime

Source: Syrian Network for Human Rights

Cumulative number of people

disappeared by the Syrian regime

Source: Syrian Network for Human Rights

The details of Oqba’s disappearance and his fate may have remained a mystery had it not been for Yasmen’s tenacity and a whistleblower that changed the course of her search.

Code-named Caesar, a military defector smuggled 53,275 photographs out of Syria in late 2013. He was the official forensic photographer for the Syrian authorities.

This cache of images would come to be known as the Caesar files.

Amongst the photographs, evidence of crimes against humanity - images of detainees who reportedly died from torture, starvation, beatings and disease in Syrian regime facilities.

Yasmen’s brother Oqba was among the dead.

One of 6,786 victims eventually identified in the photographs.

For Yasmen, learning Oqba’s fate was agonising, but the pain was made worse by losing more of her brothers while she waited for news.

“We waited and waited for so long and this caused so many losses,” she says.

“If we knew of his death when it happened, maybe we would have left Syria before we lost Tishreen, Obaida and Bashar.”

In the depths of her grief, Yasmen was haunted by the injustice of it all.

“One way to survive and move on from the tragedy…was to find a purpose or a goal,” she says.

“I could have collapsed and retreated to a corner in my house crying and wailing all day. But I know this will not help me or bring back my brothers.

“I found that the best way to continue with my life and to honour my brothers is to prevent other families from suffering my loss or experiencing my tragedy.”

Now living in Germany, she is fighting for the right to know what happened to tens of thousands of missing people in Syria and to hold those responsible accountable.

“A right is never lost, as long as someone strives to claim it.”

Yasmen’s brothers left behind 20 family members who she felt compelled to take care of.

Much like hers, thousands of other families have faced loss and the despair of not knowing the fate of their loved ones.

With this in mind, in 2018, she banded together with other relatives of those identified in the defector’s photographs and co-founded the Caesar Families Association (CFA).

CFA developed facial recognition software that spares families the trauma of searching through photos, looking for identifiers such as scars, birthmarks, tattoos or unique facial features.

For Ezzat Alian and his brother Mohamad, searching for their father was a painstaking process.

When they were only young teens, their father Khaled was arrested by Syrian government authorities in Damascus in January 2013.

“I can remember every moment,” Ezzat says.

“When they arrested my father, he had all our money. He wanted to bring it to the hospital for my uncle because he had a gunshot in his foot.

“[The regime] thought he was going to give that money to opposition fighters.”

Khaled was taken to a regime prison and was never seen again.

For two years and two months, the Alian family waited for news.

“There were people that said they had information about him, but they were all liars,” Ezzat says.

The turbulence of not knowing was unbearable, as his family tossed between hope and despair.

“Keeping waiting is burning hearts,” he says.

It wasn’t until they trawled through the Caesar Files that they discovered his fate.

It was Mohamad who went through the photos individually, searching for his father.

“I had to scroll through a lot of pictures of mutilated faces and tortured bodies,” Mohamad says.

“I remember I saw hundreds of pictures and they were all the same, all with bruises and faces full of blood. But my father’s face was different, I recognised him immediately.

“I felt that he was smiling at me in that photo. Others might see him as the rest of the faces in those pictures, but he was different to me.”

For years they kept their hope alive, hoping they would find he had survived. But like many of those identified in the Caesar Files, Khaled had met an early death.

“He died after just 15 days in prison,” Ezzat says.

Despite the heartbreak, the brothers feel grateful to know their father’s fate.

“I think we are still lucky to at least have his [prisoner] number with the date he died, because many families are still looking for this information, more than 10 years on,” Ezzat says.

But there are still many unanswered questions for Ezzat and Mohamad.

“I want to know what rights my father had.

“Until now, we still don’t know if they buried him respectfully or not.”

After hearing about its mission to gather data on missing persons, Ezzat contacted the Caesar Families Association to try to find these answers.

As new reports continue to flow in, CFA’s work remains a key resource for those left behind.

But the team not only helps those whose relatives have been disappeared by the regime, but by any group across Syria.

“I thought no one should go through what I experienced and lose so many people,” Yasmen says.

There are a host of organisations fulfilling various roles in the search for missing persons - each one a different link in the chain.

Some gather information for the purpose of prosecution, others purely collect testimony from former detainees.

“It is a complex operation,” Yasmen explains.

And so CFA, together with a collective of other groups, launched the Truth and Justice Charter, and began to lobby the UN for an international body dedicated to their cause.

“Having one institution that unites the multiple efforts aimed at revealing the fate of the disappeared and preserving evidence is crucial.”

“It would also help to significantly reduce the suffering of victims’ families, by providing one centralised place for families to turn to when they seek answers about their missing loved ones.”

After years of silence from the international community, in late 2022 UN Secretary-General António Guterres recommended the creation of such an institution.

At the time of writing, Yasmen is preparing to fly to New York to meet with representatives from Argentina, Chile and Mexico, all throwing their support behind the now-global initiative.

Yasmen has had to appear before the UN, lawyers and decision makers numerous times to recount the loss of her brothers and she describes how devastating it still feels.

“Nothing is easy about telling my story,” she says.

“I try not to cry…so I don’t look weak. I know there is nothing shameful about crying, but it is important to stay strong to encourage them to make initiatives and take action.

“I don’t want them to comfort me and say ‘Oh, poor Yasmen, you made us cry.’ No, I don’t want this. I want them to take effective steps.”

Beyond procedural justice, Yasmen hopes it will bring closure to families who have spent years waiting for truths that have been kept from them.

Despite the tragedies they have endured, Ezzat says his family will recover and he is determined to change his story.

His family fled the war and came to Australia, settling in Adelaide, where Ezzat is now studying to become a pilot.

“It has been my dream since childhood,” he says.

“Whenever I heard the sound of a plane flying in the sky, I would look at it and watch it as it was flying. I loved living in the sky and among the clouds.

“I always imagine myself sitting in the cockpit, flying through the clouds, feeling joy and pride in what I’m doing with something I love.”

More than his own dream, he hopes it will mean something for his father.

“I will make him proud.”

To those still seeking information about their loved ones, he leans on what brought his family some peace.

“Just be patient and the truth will appear.”

Tens of thousands of people are still searching for answers on the fates of their missing relatives.

Watch more of Dateline's coverage on Syria here:

Producer: Rhiona-Jade Armont

Designer: Synthura Sandrasegaran

Arabic Calligraphy: Mariam Theyab

Data Assistance: Kenneth Macleod

Graphics Assistance: Jasmine Xie, Leon Wang, Jono Delbridge

Translations: Jameel Karaki, Hana Yassin