On the day he disappeared, 28 April 2023, Gene Roz Jamil 'Bazoo' de Jesus sent a message to his family group chat. "Good Evening," he wrote.

His mother, Mercedita Centeno-De Jesus, responded instantly. It was just after midday in Italy, where she lives, but in their home country of the Philippines, where Bazoo was, it was early evening. She didn’t hear anything more until the next morning, when Bazoo's workmate contacted the family to say he hadn’t come into the office and wasn’t answering his phone.

Bazoo had started working for the Philippine Task Force for Indigenous Peoples' Rights, a network of non-government organisations, just a month earlier. He was also a proud activist.

Mercedita recalls that it was not uncommon for him to be harassed by state authorities for loudly criticising the government on issues relating to environmental impacts and the forced displacement of indigenous people. This was nothing, though, compared to what a witness would later describe having seen on the night of 28 April.

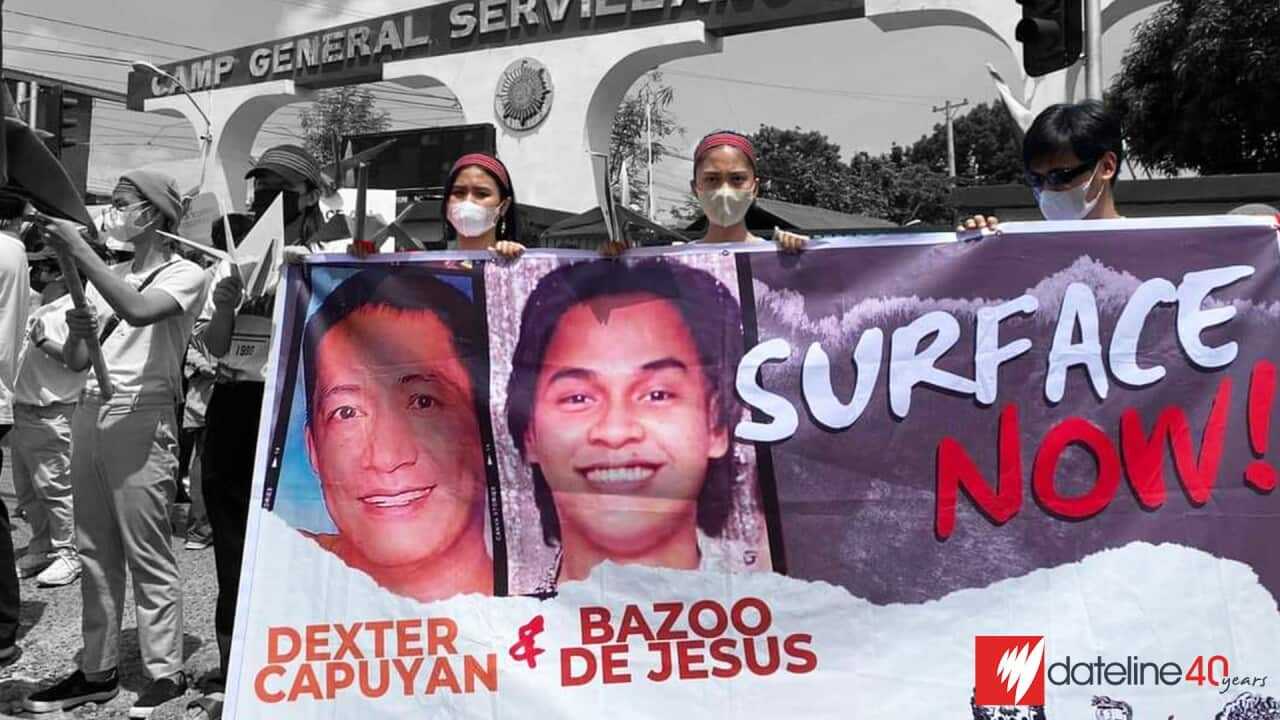

A tricycle driver told authorities he was taking Bazoo, 27, and his friend Dexter Capuyan, 56, another outspoken activist, back to their accommodation in the city of Taytay when a group of uniformed men with guns crossed their path.

The men introduced themselves as being from the Philippine National Police Force's Criminal Investigation and Detection Group. Then they reportedly escorted Bazoo and Dexter into two separate white vans, gave the driver a warning, and sped off.

Neither de Jesus, nor anyone she knows, has seen or heard from her son since. She suspects that state forces were behind his abduction, due to what she describes as "a certain pattern of disappearances of activists and human rights defenders".

"As a mother, what I am after now is to locate where they kept my son if he is still alive, or where they buried him," she said. "It breaks my heart that my only beloved son suffered so much from their hands just because he is an activist."

Mercedita De Jesus (second from right) continues looking for her son, 'Bazoo' De Jesus (right), seeking justice for his disappearance despite having been red-tagged herself. Source: Supplied

Red-tagging

The Philippines is the most dangerous place in Asia, and one of the most dangerous in the world, for environmental activists.

At least 281 environmental defenders were killed in the country between 2012 and 2022, including demonstrators, park rangers, lawyers, journalists, and state officials. More than 80 per cent were linked to protests against corporations, according to non-government organisation Global Witness, and a third were linked to the mining industry.

Many, like Bazoo, were smeared as communist sympathisers before they disappeared.

Filipino authorities have long used the tactic of 'red-tagging' to crack down on dissent: publicly accusing perceived agitators of being affiliated with the country’s communist insurgency, the New People's Army, as a precursor to harassment, abductions, torture, and extrajudicial killings.

The problem escalated under former president Rodrigo Duterte, who made red-tagging his government’s official policy and established a national task force to hunt down and weed out alleged communists.

During the presidency of Rodrigo Duterte, red-tagging became the official policy enabling the government to target journalists, environmental defenders, and other critics.

At least 11 more have been killed. Among the disappeared, or "desaparecidos" as they're locally known, were Dexter Capuyan and Gene 'Bazoo' de Jesus.

In many cases, activists claim, these counterinsurgency witch hunts are strategically targeted at those who stand in the way of government agendas — most notably, environmental defenders who oppose development and extractive mining projects in indigenous peoples' ancestral lands. The Philippines has some of the world's most valuable mineral resources, with an estimated $1 trillion worth of untapped copper, gold, nickel, zinc, and silver reserves.

Duterte sought to cash in on these lucrative deposits when he overturned a nine-year nationwide moratorium on new mining projects in April 2021, a move condemned by human rights groups who claimed it could further imperil land defenders.

Just over a year later, Marcos Jr stoked similar fears when, in his inaugural State of the Nation address, he flagged the mining of the Philippines' abundant natural resources as a key driver of post-pandemic economic growth.

Over the past 18 months, those fears have proven well-founded.

"Extrajudicial killings and attacks continue because the same policies and laws that were used by the previous regime are being pursued until today," said Windel Bolinget, an indigenous Igorot leader and chairperson of the social justice organisation Cordillera Peoples Alliance (CPA).

"The basic policies of state persecution against indigenous peoples, environmental defenders and human rights defenders are continuously being implemented."

Challenging the terrorist label

On 7 June 2023, the Philippines’ Anti-Terrorism Council designated Bolinget and three of his colleagues 'terrorist individuals', but it wasn’t until a month later that he heard anything about it — when it was published in a national newspaper.

The designation, made under powers granted by the Anti-Terrorism Law of 2020, was issued without a legal hearing or due process, he said.

"To be designated a terrorist is already a death sentence," Bolinget told SBS Dateline. "You are declared as an enemy of the state, and therefore, considering the impunity across the country, any possibility can happen—including being abducted or extrajudicially killed."

Windel Bolinget has long been targeted by the government for his activism: from being designated a terrorist to being charged with murder and put on a wanted list. Source: Supplied

"[This] is why the Philippines is not a safe country for environmental activists."

This, however, was far from the first time Bolinget had been targeted. In 2006, when he was general secretary of the CPA, his name was included on a military hit list. In 2018, when the New People's Army was officially designated a terrorist organisation, he was named as an affiliate.

In 2020, he found himself the subject of a murder charge, a shoot-to-kill order, and a bounty, based on groundless allegations he'd killed another indigenous leader two years earlier.

Large tarpaulin posters bearing his headshot were strung up around town, some of them just a few hundred metres from his house. Fearing for his life, he sought protective custody.

In all three of these cases, the designations were overturned. Now he is fighting back against the latest smear campaign in what he calls a 'national landmark case': the first time someone has challenged in court their designation under the Philippines' Anti-Terrorism Act.

Bolinget and CPA hope it will also pave the way towards a review of the constitutionality of the Act, and potentially lead to its repeal. If he fails, though, he fears the consequences will be profound.

"This case is the first of its kind, the first case of questioning the designation of terrorists," he said. "And if this case goes wrong, then it'll open the floodgate for the Anti-Terrorism Council to be just designating activists or any opposition a terrorist to silence them. This will set a political precedent. If it's dismissed or goes wrong, then it has a serious implication."

Seeking justice

While Bolinget might hope to have his designation overturned for a fourth time, though, he is unlikely to single-handedly change the status quo. Activist groups are fighting for national and international organisations to launch an independent investigation into the Philippines' human rights situation.

One of the more vocal advocates is Beverly Longid, national convener of indigenous rights organisation Katribu.

As a long-time environmental defender, Longid, like Bolinget, is well-versed in the tactics of red-tagging. She recalls being labelled a communist sympathiser even before joining Katribu in 2009, and has for years received anonymous death threats via social media and in, some cases, direct text. She's learned to take them seriously.

"Many of those that have been arrested and facing fabricated charges, those who have been killed and those who have been disappeared, have experienced this red-tagging," she told Dateline SBS.

"So at one point, you learn to always look behind your shoulder. Your daily routine is not a routine anymore; you try to change the time you come home or the time you leave etcetera."

Beverly Longid (centre) and Mercedita De Jesus (second from the right) at a press conference demanding information on the whereabouts of two activists, Dexter Capuyan and Bazoo De Jesus who are believed to have been abducted by state security forces. Source: Supplied

Longid also said the problem has persisted under the current Marcos administration. "It's the same policies, the same government structure, the same agencies, and the same people. So nothing really has changed," she said.

The risks of red-tagging and continuous threats, however, have not deterred her.

"I believe in what I'm doing; It's right. Being an environmental or a climate activist goes against people in power, so in that sense, it is necessary. But it's also very dangerous work."

Mercedita de Jesus, too, says she will "never give up" looking for her son and seeking justice for his disappearance, despite being stonewalled at every turn, and having now been red-tagged herself from the other side of the world.

After months of searches, rallies, media appearances, and court hearings, the Philippines government ignored her family’s pleas for help, she said.

Now she’s planning to launch a fresh round of searches and take her case back to the Court of Appeals. During two court hearings in August 2023, both the Filipino military and several arms within the police force denied any involvement with Bazoo's disappearance. But de Jesus isn’t abandoning the cause.

"They denied their involvement, yet they did not extend help to look for the two missing persons," she said. "They said that activists deserve it because they are always against the government."