In December 2021, journalist Masha Froliak flew from New York to Ukraine to celebrate New Year's Eve with her family and friends.

They gathered in her parents' home in the capital Kyiv, and her dad cooked traditional dishes. They watched televised greetings of President Volodymyr Zelensky ringing in the new year, and then the countdown to midnight began. Guests clinked their glasses and made wishes for the year ahead.

“The mood was so celebratory and joyful,” Froliak told SBS Dateline. “I could never imagine how much tragedy was ahead, just a couple of months away.”

“I could never imagine that I would be looking at a mass grave, or see destroyed towns and burnt-down tanks just an hour's drive from my parents’ apartment.”

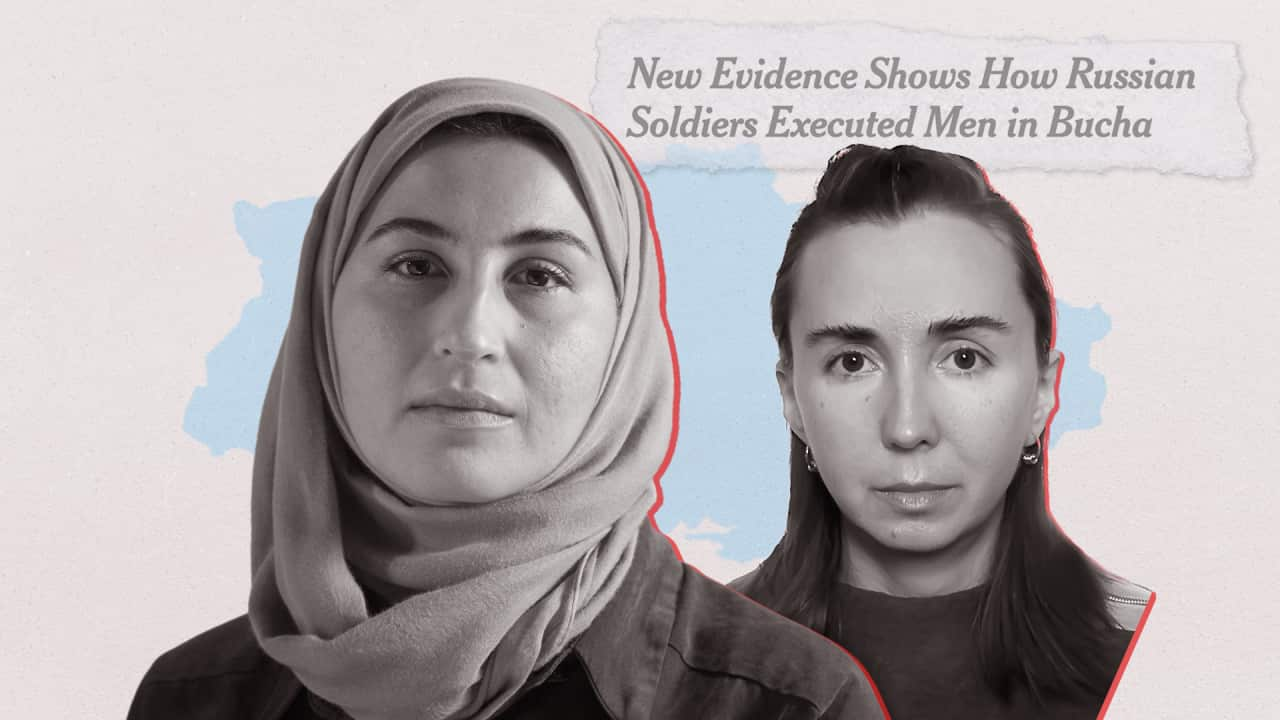

In early 2022, Froliak, who had freelanced for New York Times before, teamed up with the Times’ video journalist, Yousur Al-Hlou. The pair went to eastern Ukraine to get a pulse on the ground as Russia amassed troops on the border with Ukraine and US officials warned of an imminent invasion. When the war broke out, they were in Kyiv.

Over the next 16 months, the pair would capture and document some of the war’s most pivotal moments to date, offering a poignant insight into the human side of the conflict through the stories of Ukrainians affected by it. Their work in Ukraine, as part of a team covering the war, won the New York Times a Pulitzer Prize in International Reporting this year.

Yousur Al-Hlou (centre), a video journalist for The New York Times, spoke about the pain she endured with her work in Ukraine during a celebration after the Pulitzer Prize announcements in the Times newsroom in New York in May. Credit: Sarah Krulwich / EPA

“In terms of scale, intensity and the ripple effects, it's the defining conflict of our generation as reporters.”

If more people were exposed to the real effects of war — what it really looked liked, smelt like and felt like — would we be less likely to start another one?Yousur Al-Hlou

Searching for the truth of what really happened in Bucha

While the two journalists primarily focus on documentary filmmaking, one of their most noteworthy works is an investigation into alleged Russian atrocities in the small Ukrainian town of Bucha that was liberated in April 2022.

The month-long Russian occupation of Bucha, about 25 kilometres northwest of Kyiv, had virtually cut it off from the outside world. After Ukrainian forces retook control of the town, they discovered hundreds of bodies of local residents — men, women and children — on the streets and in mass graves. The Russian government denied the accusations of a massacre saying images of bodies were a ‘staged performance’ by Kyiv.

What happened in Bucha became one of the defining moments of the war and helped galvanise international support for Ukraine. Similar atrocities against civilians such as summary executions, torture, rape, and forced disappearances would later be documented by international human rights groups and Ukrainian investigators in other areas that had been under Russian occupation.

Bodies of civilians lie scattered on a street in Bucha on 2 April 2022. The shocking images of the town strewn with bodies, some with tied up hands and shot at close range, started to emerge after Ukraine liberated it from Russian troops. Source: Getty / Ronaldo Schemidt via AFP

Looking for CCTV footage and cellphone videos and photos that locals might have taken was a tall order. Parts of the town had lost electricity several days into the occupation. Moreover, Russian soldiers were consistently destroying CCTV cameras, so each moment of footage found was priceless, Froliak said.

Al-Hlou said: “By the end of our reporting, we had over 20 terabytes of footage from various sources: CCTV, original footage, UGC [user-generated content] and drone photography."

Another complicating factor was that at the time of their reporting, there was no centralised database of victims who were killed in Bucha. In the first days after the liberation, the Ukrainian authorities were overwhelmed by the scale of violence.

“Various branches and teams of law enforcement descended on the scene at the same time to work quickly. That meant that they employed differing methods for documenting and removing the bodies,” Al-Hlou said.

“So, while we understood that hundreds of civilians had been killed throughout the town, we didn’t know their identities or where they were killed.”

Throughout months of investigating the executions in Bucha, Froliak and Al-Hlou sifted through hundreds of case files and reviewed hundreds of graphic images of dead bodies.

They also spent many hours speaking to family members of the victims they would come to identify. Through those testimonies as well as text messages, social media posts, and satellite imagery, they were able to reconstruct of Russian atrocities in Bucha.

“It was important to set the record straight,” Froliak said.

“Russian officials claimed their soldiers had nothing to do with the killings of the civilians. We proved otherwise.”

Capturing the personal horrors of war

For their latest documentary from Ukraine, the pair embedded inside a military field hospital in eastern Ukraine for a week. They filmed a team of combat medics treating a never-ending influx of wounded soldiers and wrestling with their own trauma, anger, and exhaustion.

Many scenes are graphic: blood oozing from open wounds, faces contorted in pain, white bags containing bodies of those who couldn’t be saved.

But the New York Times reporters chose not to blur or shy away from the harrowing reality they witnessed. War is bloody and grotesque, Al-Hlou said, and there’s no way around it.

“We wanted to maintain the authenticity of what we witnessed and captured in the field, and to present it in an impactful and thoughtful way to our readers and viewers,” she said.

Against the backdrop of the heinous scenes they have witnessed, the lingering question for Al-Hlou is this:

“If more people were exposed to the real effects of war — what it really looked liked, smelt like and felt like — would we be less likely to start another one?”

For their latest documentary, Al-Hlou and Froliak spent a week with combat medics and wounded soldiers on the front line in eastern Ukraine. Source: The New York Times

‘Nothing prepares you for war’

It was the first time Froliak had witnessed a war. The experience was made even more difficult and confronting by the fact her home country was attacked by the country where she used to have many friends.

“So it’s personal, and there were a lot of questions in your head like, how could this happen?” she said. “You’re trying to wrap your head around everything that’s unfolding plus you’re trying to cover it.”

For Al-Hlou, a Syrian-American, the war in Ukraine evoked familiar imagery of mass exodus and displacement. Seeing Ukrainians walking to the border with their luggage, children and pets brought memories of Syrians boarding overcrowded boats to seek safety across the Mediterranean.

“One was on foot, one was on sea, but they're the same emotion, and it's the same conflict, the same trauma, and it's just shocking that it can continue to happen,” she said.

Al-Hlou shares that despite her background in conflict reporting, ultimately, “nothing can prepare you”.

“Seeing dead bodies on the ground doesn't get easier. I think you begin to understand it's part of war, but it doesn't mean it's easy.”

Combat Medics has been produced by the New York Times and will air on SBS on Dateline on Tuesday, 25 July at 9:30pm or on