In Myanmar, I was given a ‘White Card’. I needed this card to travel within my own town. I was banned from going to other cities and I couldn’t get a passport. I had, effectively, a temporary residency permit in my own country.

I was allowed to go Sittwe, another major city, to attend university. It is the only university Rohingya people like me were allowed to attend. That all changed in 2012. Rohingya, and other Muslim ethnicities, became the victim one of the largest massacres against my people.

I was at university at that time. The Rakhine people and military were surrounding Rohingya villages. I could not leave the dormitory. I did not eat for days.n

We were sent back to our hometown where we were targets, regardless of age. They would arrest people in their homes and either kill them, or make them disappear. I had to stay hidden. As the violence escalated, people started to flee.

I fled to Bangladesh in a small paddle boat. I tried to seek asylum there, but there was no future for me.nn As I hoped to continue my studies, I thought Yangon, the largest city in Myanmar, would be a safe city. I managed to make my way there, walking and travelling by bus from the dangerous Indian-Myanmar border. If I was caught, I could have been shot dead. When I arrived in Yangon I discovered hate and racism against Muslims and minorities had spiked and spread throughout Myanmar.

As I hoped to continue my studies, I thought Yangon, the largest city in Myanmar, would be a safe city. I managed to make my way there, walking and travelling by bus from the dangerous Indian-Myanmar border. If I was caught, I could have been shot dead. When I arrived in Yangon I discovered hate and racism against Muslims and minorities had spiked and spread throughout Myanmar.

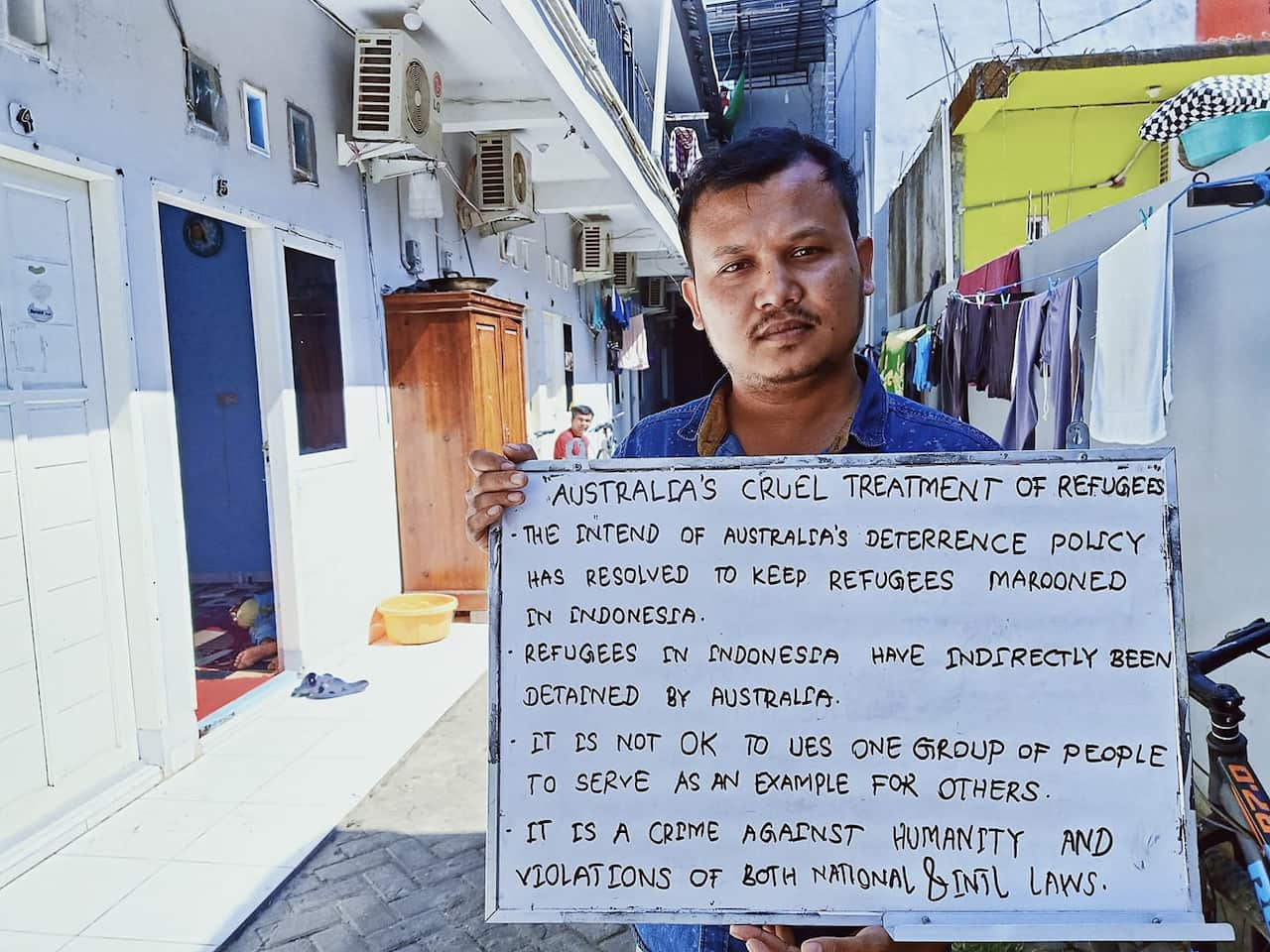

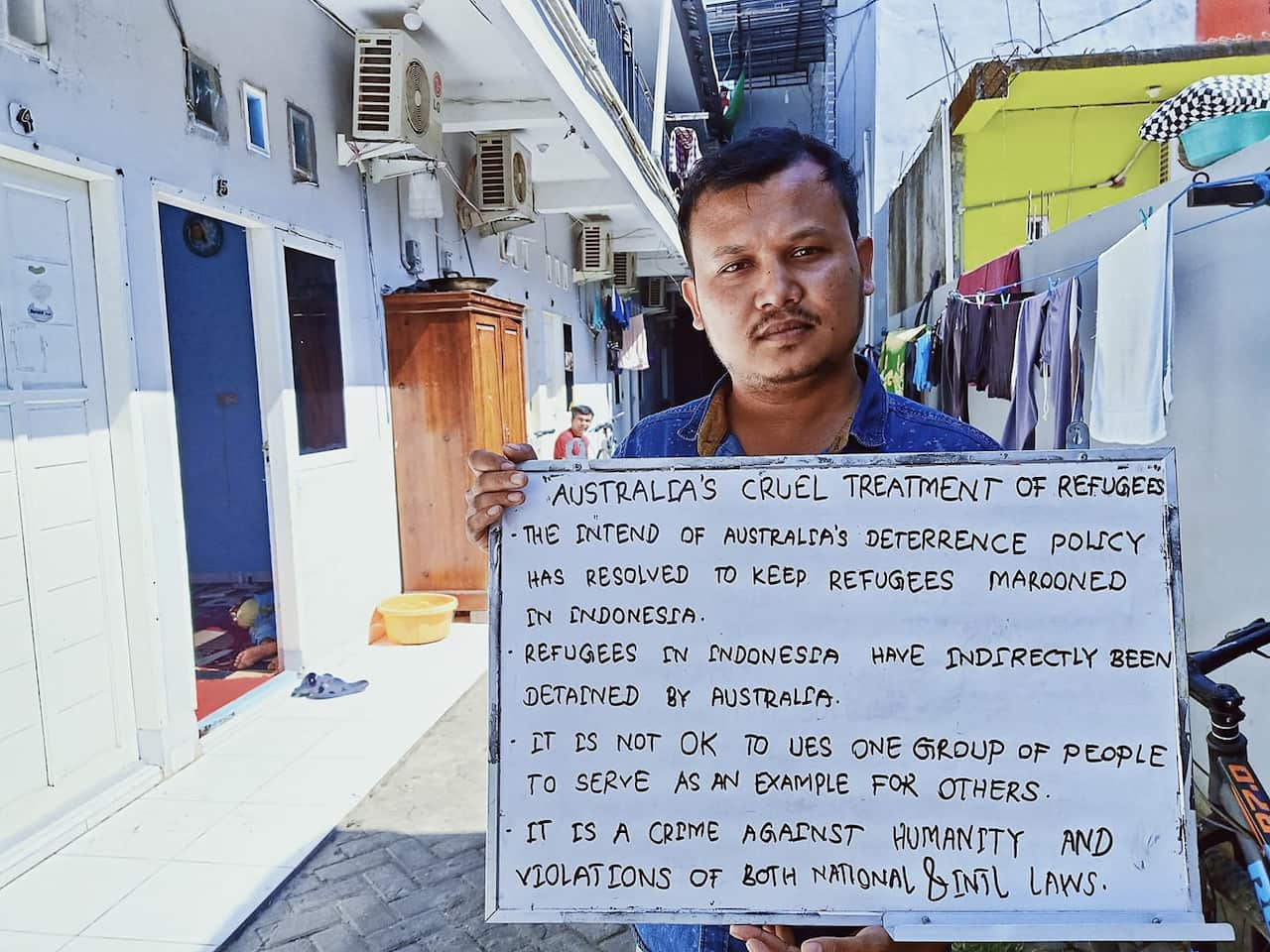

JN Jonaid protests his treatment in Indonesia. Source: Supplied

They would arrest people in their homes and either kill them, or make them disappear. I had to stay hidden.

My cousin and I decided to go to China to find work. We took a bus from Yangon to Muse, the border city of Myanmar and China.

In 2013, I returned to Myanmar only to see the situation had worsened and Myanmar had become completely unstable for Muslims. Previously, Rohingyas were targeted by the Rakhine people and the military, but now, the whole Burmese community that turned on Rohingya and the Muslim community as their monks spread hate speeches.

I still didn’t have a passport so I had to walk through the jungle, get on an overcrowded bus and hide with others under cargo goods. We slept in the forest in Thailand.

I finally made it across the Malaysian border, where I had hoped for the opportunity to rebuild my life. But Malaysia doesn’t recognize refugee rights. So, I decided to continue on to Australia where I hoped to seek asylum and rebuild my life.

Source: Dateline

Life in Indonesia

I got on a boat to Indonesia, but before I could make it to Australia I was arrested at sea. Indonesian authorities detained me for almost two years. Eventually, I was released into community housing in Makassar, where I have been living in an "open prison" for last six years.

I was 19 years old when I first fled my country. I had no idea how politics worked. I thought I would be welcomed and given the freedom to rebuild my life. This is far from reality. Now, I am 26 and in limbo.

In Indonesia, they call me an illegal immigrant and they treat me like an alien. I do not belong anywhere.

Whilst Indonesia is not a signatory of the 1951 Refugee Convention, it has opted not to deport asylum seekers and refugees back to war and conflict affected countries.

In 2016, Indonesian President Joko Jokowi issued a decree which, for the first time, acknowledged the presence of a refugee community in Indonesia, breaking away from the usual practice of describing them as “illegal immigrants”.

However, this decree appears to be more symbolic than effective as local authorities still continue to restrict refugees' basic rights.

They call me an illegal immigrant and they treat me like an alien. I do not belong anywhere.

My situation in Indonesia is almost similar to what I faced in Myanmar: I can’t work and I can’t go to university. I can’t travel and I have a curfew from 10 pm to 6 am. If broken any single restriction, I am in danger of going back to detention.

Most of the refugees in Indonesia are now suffering from various kinds of diseases, physical and mental. We have lost hope. I have supported many refugees who are struggling. I have voluntarily taught them English and I have helped them write letters to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees and International Organisation for Migration for medication and to request resettlement.

I have supported many refugees who are struggling. I have voluntarily taught them English and I have helped them write letters to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees and International Organisation for Migration for medication and to request resettlement.

More than 700,000 Rohingya fled Myanmar in 2017. Source: AAP

The impact of Australian deterrence policy in Indonesia

I escaped genocide in Myanmar but I cannot escape Australia’s immigration policies.

I tried to seek protection in Australia because it is a signatory to the UN refugee convention and claims to promise refugees protection. Therefore, I thought it was legal for me to go to Australia and seek refuge with or without a visa.

But the country I risked my life to travel to has shown only cruelty towards me and other refugees.

In 2014, Prime Minister Rudd announced that refugees who had arrived by boat after July 2013 will never be resettled in Australia.

Nearly 14,000 vulnerable refugees in Indonesia, myself included, are in permanent limbo, according to UN figures release last year.

It seems Australia hopes that the sight of refugees driven to despair will discourage others from coming to Australia through Indonesia, and will make refugees give up and go back to their country.

Refugees in Indonesia have been pushed to our limits.

If the Australian government believes that locking up refugees like cattle will end the refugee crisis, they are wrong: people movement will never stop. People will go to the end of the Earth in pursuit of freedom.