Stream free On Demand

Canada's Fentanyl Warning

episode • Dateline • Current Affairs • 28m

episode • Dateline • Current Affairs • 28m

It was the Easter long weekend. Pam Downey was cooking dinner at home in Vancouver, Canada. Her son Ronan had been watching YouTube videos in his room.

When the time came for dinner, Ms Downey found her son slumped over in his chair.

Ronan was dead. He was only 16.

Three months later, a coroner's report revealed that he had a tiny amount of fentanyl, a powerful and addictive painkiller, in his system.

Ronan had taken what he believed to be a Xanax pill, an anxiety medication that is also used as a recreational drug. Apparently, it had also contained fentanyl.

"The coroner said he must not have had any tolerance [to fentanyl] because it was such a small amount," said Ms Downey, who has since met other mothers in Vancouver who have lost their children to the same opioid.

"He didn't want fentanyl and he didn’t want to die."

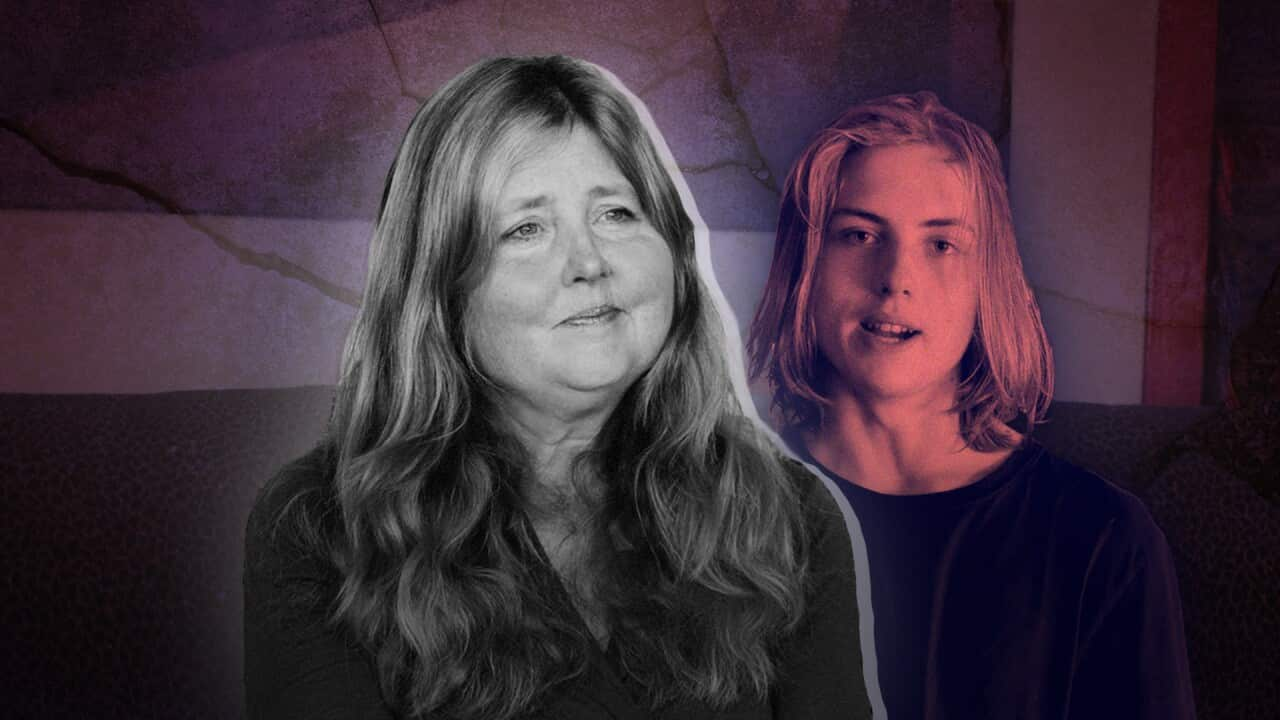

Pam Downey with her son Ronan. Source: Supplied

"Had I known about these counterfeit pills, I would have loved to have this conversation with him and any other teenager I know."

In Canada, 15 to 24-year-olds are the fastest-growing group being hospitalised from opioid overdoses. In the neighbouring United States, overdose deaths among teenagers more than doubled in three years between 2019 and 2021, with fentanyl being the leading cause.

Fentanyl is used as a pharmaceutical painkiller and is approximately 100 times more potent than morphine and 50 times more potent than heroin. As with other opioids, people can become dependent on it. But it has also become a common cutting agent in everything from heroin to counterfeit prescription pills. It means people can overdose on it accidentally if it's laced into other drugs.

Now experts and politicians are butting heads on how to deal with the growing crisis.

"This drug is indiscriminate and kills people who are experimenting, kills people who are recreationally using, and it kills addicts," Ms Downey said.

Amid Canada's ongoing opioid crisis, advocates and supporters have been calling for a safe supply of drugs as an alternative to toxic street drugs as a way to reduce overdoses. Credit: SBS Dateline

Community calls for safe supply

Since 2019, Canada has been trying to combat overdoses by dispensing opiate alternatives similar to methadone, a synthetic opioid used to treat addiction.

Recently, various community groups — from grieving mothers to drug users and public health workers — have been advocating for a safe supply of drugs.

British Columbia has the highest rate of fentanyl-caused deaths in Canada — on average six people die there each day from overdose. Its most populous city of Vancouver is believed to be both ground zero and the epicentre of the nation's opioid crisis. Earlier this year, British Columbia became the first province in the country to allow the possession of small amounts of hard drugs for personal use by people over the age of 18.

In Vancouver's Downtown Eastside, addiction medicine specialist Dr Christy Sutherland runs a world-first trial program where she aims to "break drug users up from their dealers" by supplying them with safe amounts of fentanyl in a supervised setting.

Canadian addiction medicine specialist, Dr Christy Sutherland, runs a world-first trial program in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside, where she supplies drug users with safe amounts of fentanyl in a supervised setting. Credit: SBS Dateline

"But what we can see from the research, and what I have seen in my clinical experience, is that when people are on a high-intensity program like this and stabilise, they want to move on."

While Dr Sutherland has the approval from local authorities to run her program, a rebellious duo is also working to provide a safe supply of drugs illegally.

The Drug Users Liberation Front, or DULF, sells cocaine, heroin and meth to a select group of users for the same price they were purchased at but free from contaminants including fentanyl.

"Lots of people don't get their drugs checked, or if they do, it's just once in a while. So when people get it from us, basically they're getting their drugs checked every single time they use," said Jeremy Kalicum, one of DULF's co-founders, who holds university degrees in public health and biology and previously worked at safe consumption sites.

Asked whether what they do is legal, Mr Kalicum says it’s a grey zone but he and his partner believe they can argue their case in court.

"By the written law, it's illegal to possess, sell, and distribute drugs," he said. "But in the context of a public health emergency, which is a legislative tool that public health officials have, we need to do everything we can to stop this. Is it illegal to save people's lives?"

The Drug Users Liberation Front sells drugs to a select group of users after checking them for contaminants including fentanyl with the aim to stop overdoses. Credit: SBS Dateline

Canada's conservative opposition leader Pierre Poilievre wants to see tougher policing on the supply of fentanyl and the introduction of tougher laws for re-offenders.

"There is no safe supply of these drugs, they are deadly, they are lethal, and they are relentlessly addictive," he said.

Dr Sutherland says prohibition and punishment for people who use drugs won’t work.

"It's clear and simple and wrong to say everything should just stop using drugs. It's never happened in the history of humanity," she said. "Re-envisioning a different world would be less costly, there'd be less death and then less suffering, and to me it's a policy change, it's not that radical."

Vancouver group 'Mums Stop the Harm' united parents who have lost their children to fentanyl overdose. It campaigns for more awareness about the lethal opioid. Credit: SBS Dateline

Lessons for Australia

Last year, the Australian Federal Police intercepted 11kg of fentanyl coming from Canada.

So should Australians be worried?

John Ryan is the CEO of Penington Institute, a non-government and not-for-profit organisation aiming to use research and lived experience to improve community safety around drugs.

He says Australia doesn't yet have any significant fentanyl issues. But watching the crisis unfold in North America, it really needs to pre-empt the risk.

"We've seen Australia follow the US in many drug patterns, including MDMA, cocaine and heroin. So it's logical to think that there's a significant risk of us following the US versions of fentanyl."

Mr Ryan says fentanyl is an important pharmaceutical opioid used as a powerful pain reliever in medical care, so he doesn't believe a total ban on the drug would work.

Instead, he says there should be a focus on reducing the scale of the population in Australia that is reliant on illicit drugs by improving access to health care and treatment, but also improving community understanding about the risks.

Mr Ryan says Australia could also benefit from increased access to fentanyl testing strips and naloxone, a medication used to reverse or reduce the effects of opioids.

Currently, naloxone is available over the counter at pharmacies for a fee. It can also be picked up for free at some locations including participating pharmacies and drug treatment centres as part of the national program which began in July last year.

"[The US] has really radically increased access to naloxone by providing it through all sorts of outlets including libraries and high schools," he said.

If you or someone you know needs help with drug or alcohol addition, call the National Alcohol and Other Drug Hotline 24 hours a day, 7 days a week on 1800 250 015 or visit