8 min read

This article is more than 2 years old

‘Comfort Women’: The South Korean ‘grandma’ leading the fight against Japan’s war crimes

Survivor Lee Yong-soo continues her fight for an apology and resolution on behalf of the 200,000 plus women and girls who were forced into sexual slavery under the Japanese military, before time runs out.

Published 24 May 2022 4:44pm

Updated 24 May 2022 5:37pm

By Monique Pueblos

Source: SBS

Image: Lee Yong-soo, a former 'comfort woman,' who served as a sex slave for Japanese troops during World War II, sits next to a comfort woman statue. (Chung Sung-Jun/Getty Images)

This article contains references to sexual assault and child abuse.

Over the past 30 years, from her hometown of Daegu in South Korea’s southeast, Lee Yong-soo has led the fight for the victims of Japan’s war crimes against at least 200,000 women and girls.

But at 93, her time to seek justice is running out.

“I feel so much sorrow,” Grandma Lee says.

“I will fight until the end, until I die, to receive a real apology.

“There are many victims from neighbouring countries, I want to restore their honour too … before my steps get slower and slower."

Lee Yong-soo is seeking justice for fellow survivors of Japan's wartime sexual slavery.

Most of these women, known affectionately as the ‘Grandmas’, have now passed away. Grandma Lee is one of the last survivors. While she is known as a ‘Grandma’, she has no children or family of her own.

“I didn’t get married - so I could fight Japan until the end,” she says.

In Daegu, Grandma Lee’s childhood home is long gone and her memories are patchy, but one thing she’s never forgotten is the nearby underpass where she was lured by a Japanese man to join other Korean girls.

She says she didn’t realise what was happening until it was too late.

“The soldier came behind me and poked something into my back, pushing me along, ” she said.

A frightened young Grandma Lee was taken to Daegu Station and forced on a train.

“When I got on the train, my head hurt and felt dizzy, and I told them ‘I’m not going’.

“Then the soldiers beat and kicked me, I was vomiting and crying.”

Lee Yong-soo revisits Daegu station.

“That’s why I thought it was a game. I thought it was a game until we got on the train, and they beat me, and called me Korean scum. That’s when I realised it wasn’t a game.”

It was no game. The girls were on an unimaginable journey - by train and then ship to a military base in Taiwan, via Shanghai.

I will fight until the end, until I die, to receive a real apology.Lee Yong-soo

A memory too distressing for Grandma Lee to discuss in detail, her harrowing story is one of a child’s physical, sexual and psychological abuse.

“I’m not sure how long we were in Shanghai, but one day, the boat started moving again,” she tells of her journey to Taiwan.

“I vomited and my head hurt. I went to the bathroom. As I was standing up, I saw a pair of soldier’s shoes. He was stopping me from getting out of the bathroom.

“So I remember biting very hard on the soldier’s arm. I remember up until him hitting me in the face, and I can’t remember what happened next.

“The other girls found me lying there covered in blood.

“When I opened my eyes through the blanket, I could see them pouncing on the girls. Back then, I didn’t understand why they were pouncing on them,” she says.

During Japan’s militaristic period in the 1930s that ended with World War Two in 1945, the Japanese military forced hundreds of thousands of young girls and women, many of whom were Korean, into sexual slavery.

They were euphemistically called ‘comfort women’.

Young women and girls from occupied territories across the Asia-Pacific were tricked or coerced, while others were abducted.

They were all victims of the Japanese military’s human trafficking scheme in order to enhance the morale of its soldiers and were taken to ‘comfort stations', often abroad. The survivors call it rape.

It was a dark secret kept until the 1990s when a brave group of South Korean women revealed the truth of what Japan did.

Demands for an apology from Japan

Every Wednesday, people protest outside the Japanese embassy in the Korean capital Seoul, demanding an apology.

The protest has been happening for the past 30 years. Grandma Lee used to attend regularly but has since stopped.

The protest has become a magnet for fringe groups in Korea and some people even refuse to believe the women, claiming they were 'just prostitutes'.

Ms Lee wants Japan to admit it forced Korean girls like her into sexual slavery.

But after decades of failed diplomacy, she’s pushing for a new, high-stakes strategy - to get her cause addressed by the United Nations.

In 2021 she called on former South Korea president Moon Jae-in and this month, newly elected Yoon Suk-yeol to try a new way to resolve the historical dispute so Japan would have to face history.

Lee Yong-soo of South Korea speaks during a meeting as part of the 12th Asian Solidarity Conference for the Issue of Military Sexual Slavery by Japan. Source: AFP / KAZUHIRO NOGI/AFP via Getty Images

In the meantime, they’re trying to increase pressure for that to happen, which is why they have been calling on the South Korean government to refer the issue to the United Nations Committee against Torture, which works to hold countries accountable for human rights violations.

In a video address to former South Korean president Moon Jae-in, Grandma Lee, her voice cracking with emotion, said: “I am earnestly entreating you to resolve this.

“I…will not forget.

“I will call your name, President Jae-in Moon, morning and evening, until you say those words.

“Please do this. You must do it!”

Fighting for justice

Phyllis Kim is the executive director of Comfort Women Action for Redress and Education (CARE), a community-based organisation that focuses on raising awareness about ‘comfort women’.

She is part of a younger generation of activists inspired to help the Grandmas and is hopeful of seeing a resolution from the government.

“It was state-led institutionalised sexual slavery and it was one of the largest cases of the 20th century and it’s not a thing of the past,” Ms Kim says.

“Even if all the victims pass away, I don’t think this issue will go away, because people are waking up.

“She [Grandma Lee] really wants to get a resolution while she is alive so that she can go to heaven and tell other victims, ‘Hey, I resolved this.’”

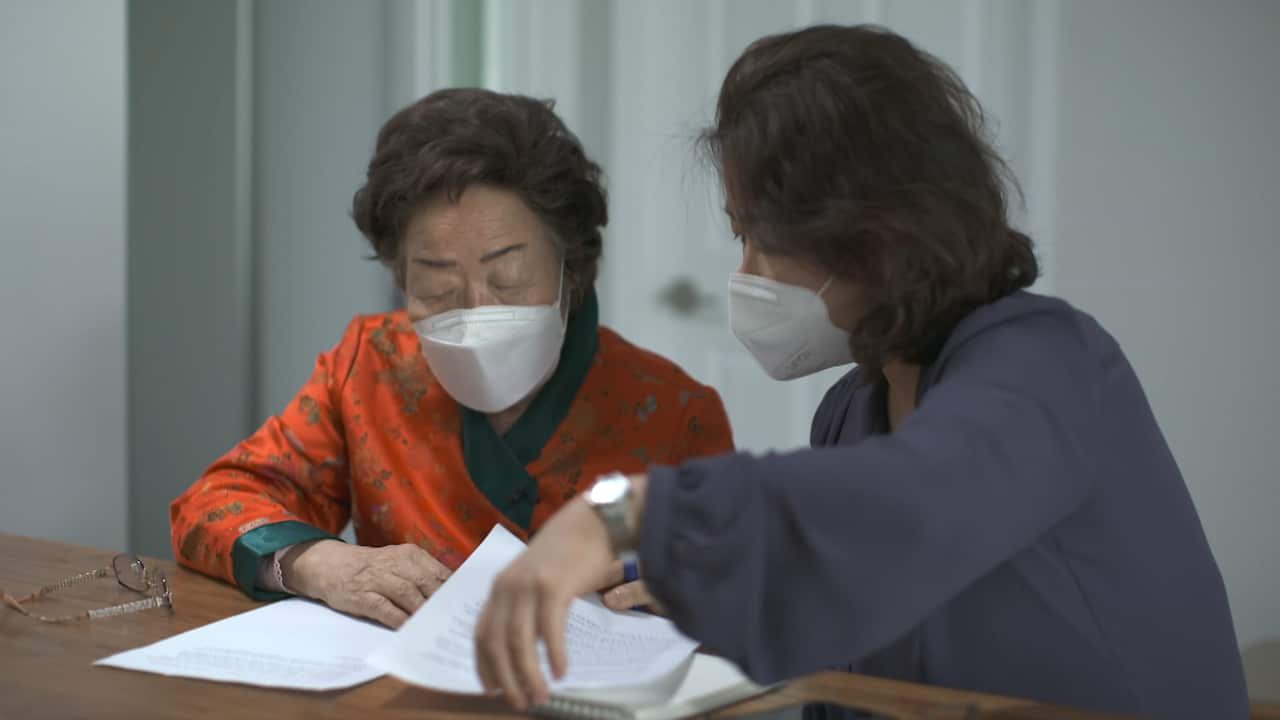

Phyllis Kim is helping Lee Yong-soo fight for a resolution.

She takes a trip to visit her friend Pilgeun Park, who is the other last known survivor in their region.

Grandma Lee says there would be other survivors in the area who are much too shy to come forward.

It was state-led institutionalised sexual slavery and it was one of the largest cases of the 20th century.Phyllis Kim

Grandma Park says she’s not too keen on fighting for an apology from Japan.

“Too much time has passed. I could die today; I could die tomorrow. What’s the point now, when I’m at the end of my life,” Grandma Park says.

But Grandma Lee says to her friend that her mission is to go out in public, be their voice and achieve a resolution.

“That’s why I work so hard - for all the people who had this happen to them but haven’t been able to say a single word about it.”

Grandma Park replies, “I should do the same… I should with my heart.”

An archival photograph of Korean 'comfort women' who were forced into sexual slavery by the Imperial Japanese Army. Credit: Pictures from History/Universal Images Group via Getty

Japan expressed remorse for the suffering it caused and set up a compensation fund. But Grandma Lee and other survivors were furious as nobody ever consulted them.

She says they don’t want money, but for Japan to take legal responsibility for its war crimes.

Her frustration with politicians, especially the government, is starting to tip over the edge.

“Lawmakers are just waiting for all the survivors to die out,” she says.

But there is one woman who continues to be a source of strength for Grandma Lee.

A special place to her is where the statue of Hak-soon Kim stands tall on Namsan Mountain in Seoul. She was the first survivor of Japan's wartime sexual slavery to come forward publicly in 1991.

There, Grandma Lee renews her pledge to fight for all those for whom it’s too late to say sorry.

If you or someone you know is impacted by sexual assault/abuse, call 1800 RESPECT on 1800 737 732 or visit