Key Points

- What the government can do to bring down power prices.

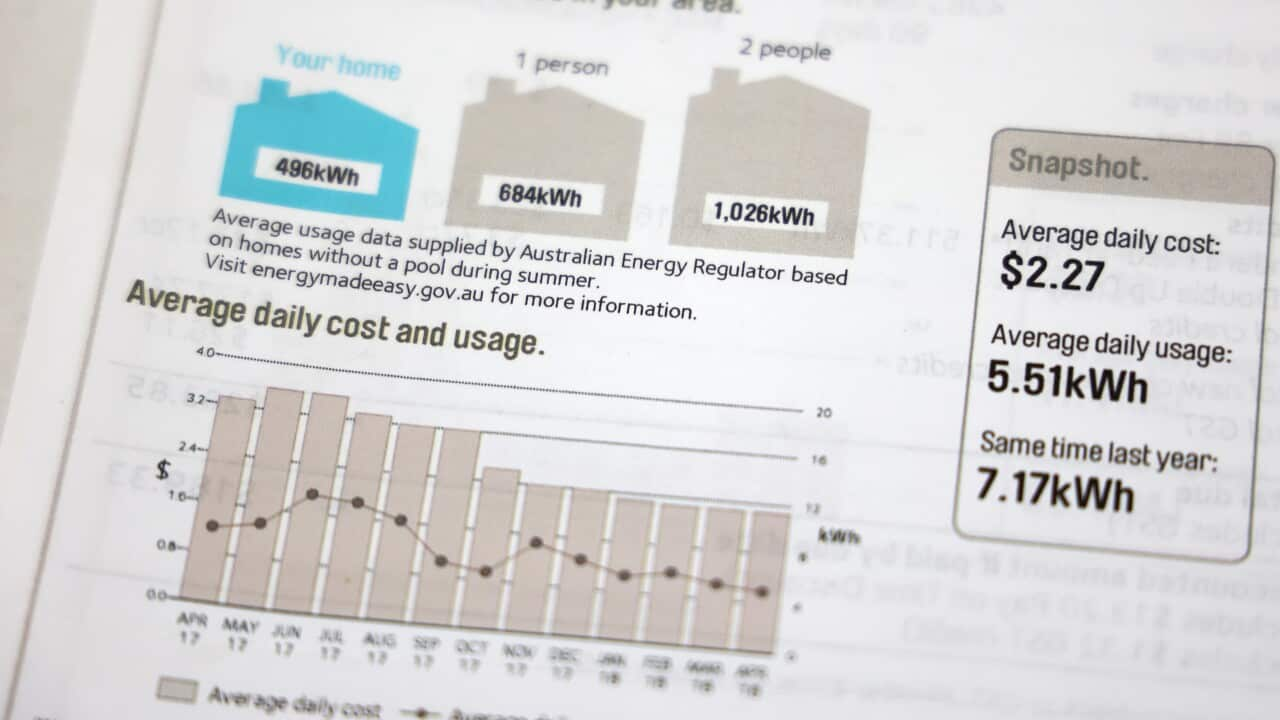

- Electricity prices are forecast to rise by 50 per cent over two years.

- No direct payments have been promised to help households but experts say there are other options.

No direct measures to bring down electricity prices were included in the budget - despite forecasts they could rise by 50 per cent - but the Albanese Government has hinted it is looking at 'regulatory measures'.

Tuesday's budget forecast electricity prices in Australia would rise by an average of 20 per cent this financial year, with a further 30 per cent rise next financial year. Gas prices were expected to increase by up to 20 per cent in both 2022–23 and 2023–24.

This would see electricity prices rise by around 50 per cent in two years, and gas prices rise by around 40 per cent.

Treasurer Jim Chalmers has clarified the 20 per cent increase forecast for this year includes the period after June 30, so some of this increase would have been experienced by Australians already.

He has defended the government's decision not to provide any direct payments or other assistance to help households with rising electricity prices, but has said: "I do think there's more work to be done on the regulatory side".

So what does this mean and will it bring down prices?

Treasurer Jim Chalmers says the government is looking at "regulatory" measures to try and bring power prices down. Source: AAP / MICK TSIKAS

Why can't the government just give people money?

Australians have got used to the government stepping in to deal with cost of living pressures - one example is the that helped push down the price of petrol.

But the problem with doing this, says independent economist Chris Richardson, is that if you give people money, it means they can afford to pay more, and this just pushes up prices even further and makes inflation even worse.

When asked on ABC radio on Thursday why the government couldn't provide some relief for families due to rising electricity prices, Mr Chalmers said: "Our approach in the budget is to provide cost of living relief in a way that doesn’t make this inflation problem worse".

The Albanese Government says its investments in renewables will eventually bring down the price of electricity but this won't have an immediate impact.

What can be done to bring down electricity prices now?

Oil, gas and coal prices around the world have risen sharply following the Russian invasion of Ukraine, and companies on the east coast of Australia are sending vast quantities of gas overseas where they can sell it for a much higher price.

Mr Richardson said the key to bringing down electricity prices is reducing the price of gas.

Australia sends a lot of gas overseas where it is sold for high prices.

In September, the Albanese Government announced it had signed a to ensure enough supply is available in Australia at a "competitive price".

The agreement says that Australian gas customers would not pay more for gas than international customers.

But with prices overseas skyrocketing, there is now pressure to make this gas cheaper.

Support for a price cap

The Greens say the government should look at capping electricity prices and it's something Mr Richardson agrees would be a good idea.

"It's something as an economist, I wouldn't ordinarily rush to support, but in current circumstances they make superb sense," he said.

This would involve setting a price limit on gas sold in Australia. Mr Richardson said the market was not working well and the current rules allowed it to be gamed by some operators.

"Adding a price cap is the simplest and most direct way to achieve the outcome we need," he said.

Economist Chris Richardson says a price cap is the simplest way to bring down gas prices. Source: AAP

But Grattan Institute energy program director Tony Wood said introducing a price cap would be tricky because the prices are set through confidential bilateral commercial contracts with producers and their customers.

"It's hard for the government to interfere in that market directly," he said.

He said another similar option would be to change the Heads of Agreement between the government and gas suppliers.

Mr Wood said the agreement is quite vague about how gas prices are set and refers to the international spot price, which has risen sharply. The government could amend this to set an explicit number instead, which would still allow companies to make a fair profit.

Gas sent overseas is sold at a high price, and has made gas in Australia also more expensive.

"I'm sure what the government's doing right now is thinking through every possibility and trying to understand precisely what adverse consequences you could get," Mr Wood said.

"This will not be simple but it has to be done fairly quickly because there are consumers already [such as commercial industrial customers] who are already bearing the brunt of the very large prices."

The government has also pointed to the complexity of the task, saying work on changes to regulation involved governments at multiple levels.

"A lot of the regulatory powers are held by the states," Mr Chalmers told reporters at the Press Club on Wednesday.

What about a windfall tax?

The Australia Institute has also flagged the possibility of introducing a windfall tax to remove the incentive for producers to sell gas overseas. A windfall tax is a higher rate of tax on profits that are unexpectedly generated.

“Many LNG companies pay little if any income tax and get much of the gas for free as it’s not subject to royalties," Australia Institute executive director Richard Denniss said.

But not everyone agrees this is necessary. Mr Richardson pointed out Australia already has a windfall tax - the petroleum resource rent tax (PRRT) - it just doesn't work very well.

The Australia Institute said loopholes in the PRRT mean that despite windfall gas profits of up to $40 billion, companies are avoiding paying tax on these super profits with PRRT revenue projected to increase by less than $1 billion in 2022-23.

"It would be silly to add an extra tax if the existing one is not working well," Mr Richardson said.

He said a smarter approach would be to fix the existing PRRT tax.

"I would 100 per cent support that approach," he said.

The Albanese Government has previously ruled out introducing a windfall tax but Mr Chalmers noted that Treasury, under the leadership of previous treasurer Josh Frydenberg, had started an inquiry into the taxation of gas, which was paused due to COVID-19.

"I’ll obviously listen to the advice I get from Treasury as they conclude that work," Mr Chalmers said.

He said increasing the PRRT was not something the government was currently focused on, and it was instead looking at prices and the code of conduct.

"Our intention and our priority and our focus is on building on the work that [Resources Minister Madeleine King] has done on supply to think about price and to think about the code of conduct in the gas market."