KEY POINTS:

- Cabinet papers from 2003 have been released, shedding some light on the invasion of Iraq.

- The decision was made primarily in a secretive and powerful committee, the documents of which remain classified.

- An Iraq War whistleblower, who has since become an MP, has strongly criticised the withholding of the documents.

What drove former prime minister John Howard's decision to join the 2003 invasion of Iraq remains shrouded in mystery, despite the release of documents showing it was quickly approved by his cabinet.

Cabinet papers from 2003, released on Monday, exclude key meetings as to the mission, because he leaned heavily on the secretive National Security Committee (NSC) before the decision was hastily approved by cabinet. NSC papers have not been released.

An Iraq War whistleblower, who later became an MP, has blasted the absence of the documents as "another appalling dimension of this shocking period in Australian political history", and accused the government of "burying" evidence after decades of blaming the intelligence community.

NSC documents are typically tightly held for national security reasons, and there is no requirement for them to be released alongside cabinet papers, which are opened to the public after 20 years.

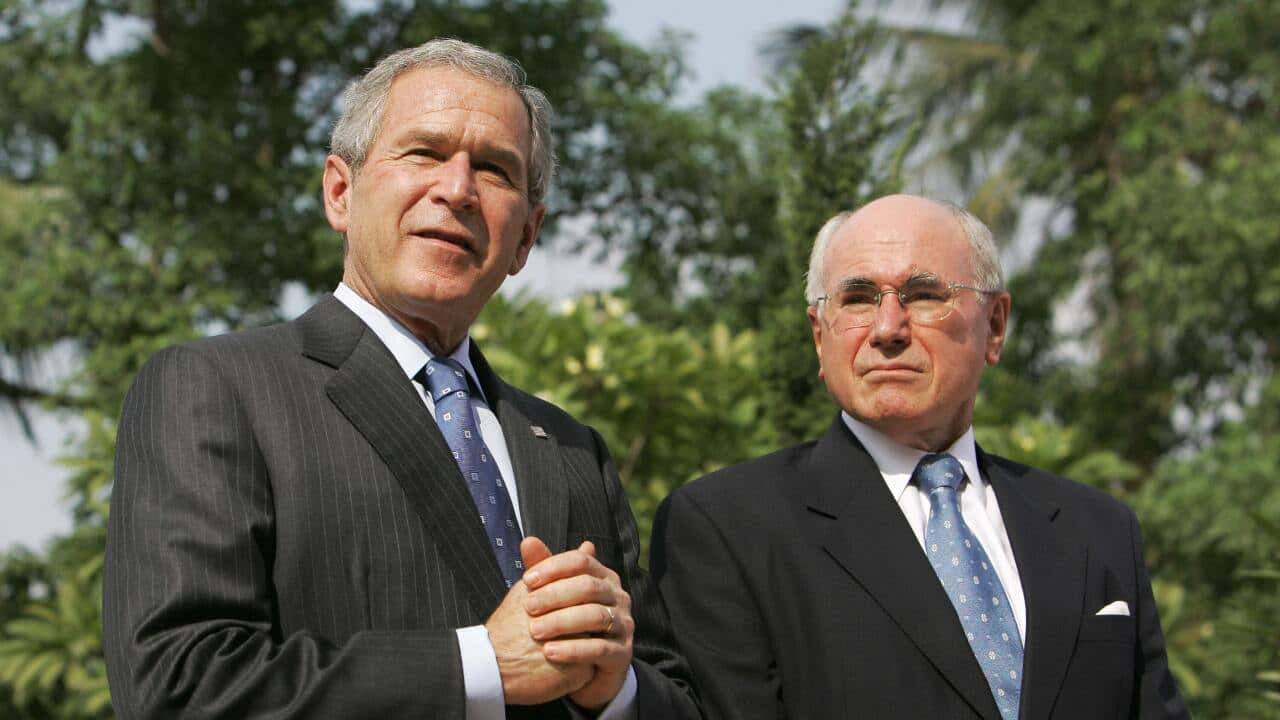

John Howard (left) committed to joining the invasion of Iraq, launched by the US under former president George W. Bush (right). Source: AAP / Mick Tsikas

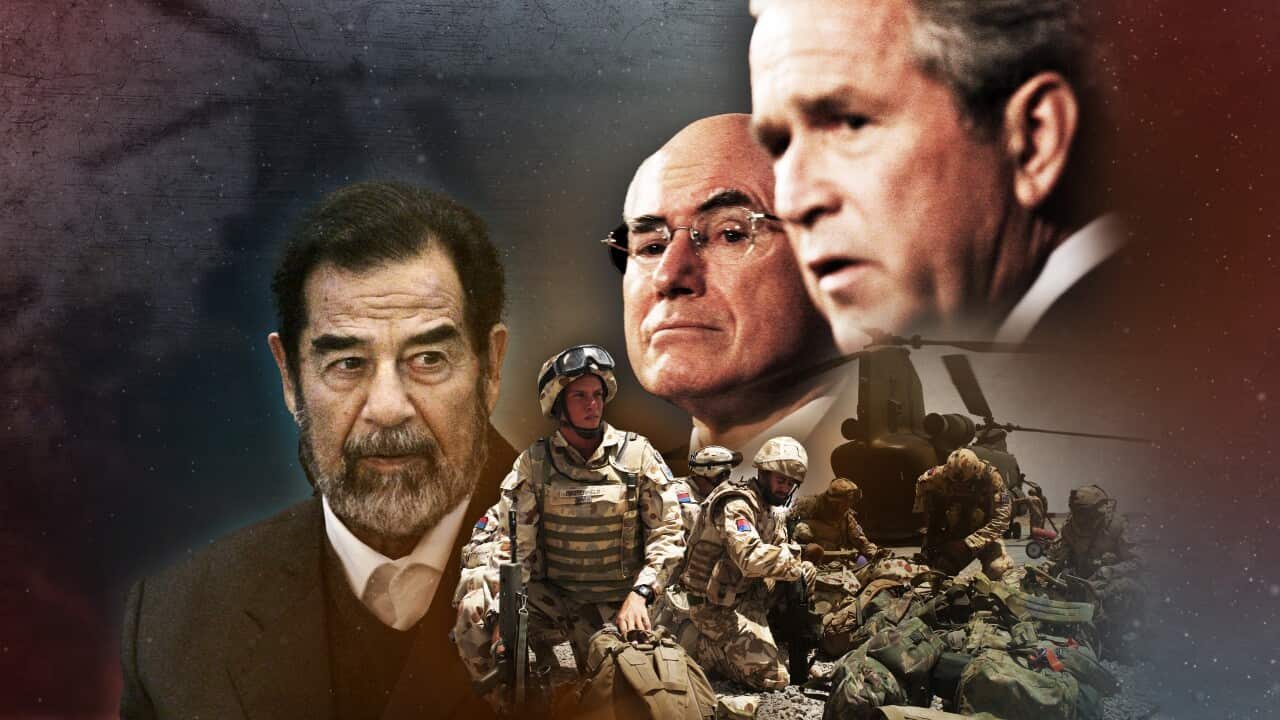

The papers show that Howard held "extensive discussions over a period of time" with then US president George W Bush and UK prime minister Tony Blair about "possible" military force if Iraqi president Saddam Hussein (WMDs).

While Hussein's regime had used chemical weapons in the 1980s, investigations after the invasion showed it did not have WMDs in 2003. A found Blair was committed to the invasion before all peaceful options had been exhausted, and that he had repeated the WMDs claim with unwarranted certainty.

Cabinet approved invasion on the day of Bush's request

In March 2003, Bush formally requested Australia join the war. The same day, the request was taken to cabinet by Howard and swiftly approved, including the early deployment of Australian soldiers to the Middle East.

The International Commission of Jurists later described the invasion as a "flagrant violation" of international law, and the then Labor Opposition led by unless it was backed by the UN.

But a record of the cabinet meeting shows the government claimed the invasion was legal and supported by "humanitarian considerations".

"The Cabinet further noted that Australia’s goal in participating in any military enforcement action would be disarmament of Iraq’s weapons of mass destruction," it said.

Speaking later that day, Howard claimed Iraq already had chemical and biological weapons and was seeking to attain nuclear warheads.

An estimated 200,000 Iraqi civilians were killed in the sectarian bloodshed unleashed by the 2003 invasion. Source: Getty / Renaud Khanh

Then defence minister Robert Hill insisted the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) was "deeply involved" in decision-making and argued the NSC's central role in the process was not unusual.

Hill told SBS News that the NSC, made up of a few top-ranking cabinet ministers, was regularly briefed by the heads of intelligence agencies in the lead-up to the invasion.

"There was detailed debate and discussion over quite a long period of time in the [NSC], and many meetings. I think it is done today exactly the same way as it was done there. This was just the practice, the way [things] developed doing these things," he said.

"I'm more in favour of transparency than otherwise ... If the records [of NSC meetings] reflect what I can recall, there's no reason why they couldn't be made public."

Then defence minister Robert Hill (right), pictured with former US secretary of state Donald Rumsfeld, insists invading Iraq was the right call based on the evidence at the time. Source: Getty / Shawn Thew

He also argued the US was so important to Australia that it was "generally in [our] interests" to support it, saying the country was "likely" to be drawn into wars in the Middle East again.

"If the intelligence had been different, it would have been a different situation," he told SBS News.

"How do I think Iraq would have turned out without the intervention? I don't think it would have ended in a happy way. I think it would have still ended, probably, in civil war and widespread violence."

Andrew Wilkie says NSC decision continues 'appalling' episode

In February 2003, an estimated 500,000 Australians turned out across 600 cities to protest against the imminent invasion.

The next month, Andrew Wilkie resigned as an analyst at the Office of National Intelligence over the decision to go to war.

Wilkie, who has been an independent federal MP since 2010, told SBS News the cabinet had been used as "little more than a rubber stamp" for a decision that was "entirely about our bilateral relationship with Washington".

Wilkie, who has long called for an inquiry similar to the one held in the UK, blasted the absence of public NSC documents as "another appalling dimension of this shocking period in Australian political history".

Andrew Wilkie quit his intelligence role over the Iraq invasion before entering parliament. Source: AAP

"Until we see this paperwork, we can't hold people to account, and we can't learn from what was a shocking error in Australian foreign and security policy."

Howard has always maintained the decision was correct based on the intelligence provided to his government.

"When you’re dealing with intelligence it’s very, very hard to find a situation where advice is beyond doubt," he said in 2016.

"Sometimes if you wait for advice that is beyond doubt you can end up with very disastrous consequences."

But Wilkie said that, while his old employer had become politicised and "fallen into line", the intelligence community was in fact split in 2003, with the Defence Intelligence Organisation, in particular, believing that there "was quite a bit of uncertainty about the situation on the ground".

That fact was obscured by two public inquiries which were "absurdly narrow" in their scope, focusing on Australian intelligence failures but excluding diplomatic cables and the ideology of government ministers, Wilkie said.

Two people were arrested after scaling the Sydney Opera House to paint this protest slogan in March 2003. Source: Getty / Greg Wood

"And now [it] has done a masterful job, we see, at burying the hard evidence of what went on within the NSC paperwork."

Australia’s parliament did not debate the invasion, though then Labor leader Simon Crean was vocal in his opposition to it without UN backing.

Wilkie rejected Hill’s explanation that a reliance on the NSC was normal practice, stressing that the "march to war" driven by the US had started the year before.

"It's patent nonsense to suggest that neither the parliament nor the broader cabinet shouldn't have a role in deciding to go to war, particularly in a situation where the decision evolves and crystallises over many, many months," he said.

Was Howard committed to war regardless of advice?

Allegations have long been aired that the Howard government deliberately avoided advice that contradicted its commitment to the invasion, including failing to ask DFAT to develop a pros and cons list.

Howard also initially wanted then governor-general Peter Hollingsworth to approve the invasion, but abandoned the idea when Hollingsworth asked the attorney-general for advice on the relevant international law.

In 2004, journalist John Garran criticised what he described as "disturbing patterns" in the government's decision-making process, especially over advice from the public service.

That included not asking DFAT to produce a pros and cons list on the potential invasion, Garran said.

An inquiry in the UK found Tony Blair (right), pictured here with George W. Bush, had committed to the war without exhausting peaceful options. Source: Getty / Jeff Overs

David Lee, historian at UNSW, said a DFAT submission to cabinet could have helped the government understand the "pitfalls" of the intelligence advice, and more fully understand the consequences of sending military forces into Iraq.

"But there's a strong sense that the government wants to support the US, and so in a way it wouldn't welcome this advice at that stage," he said.

"It's decision that's taken politically by senior ministers."

Then DFAT secretary Ashton Calvert said the department did not argue against the war, sensing Howard and foreign minister Alexander Downer were already fixed on a course.

"They didn’t need advice on what they should do because they had, in effect, made up their minds," Calvert said.