16 min read

This article is more than 2 years old

What it's really like being an asylum seeker in Australia

Only two per cent of the 70,000 asylum seekers in Australia receive income support. This is what happens to the rest.

Published 7 January 2023 7:13am

By Aleisha Orr

Source: SBS News

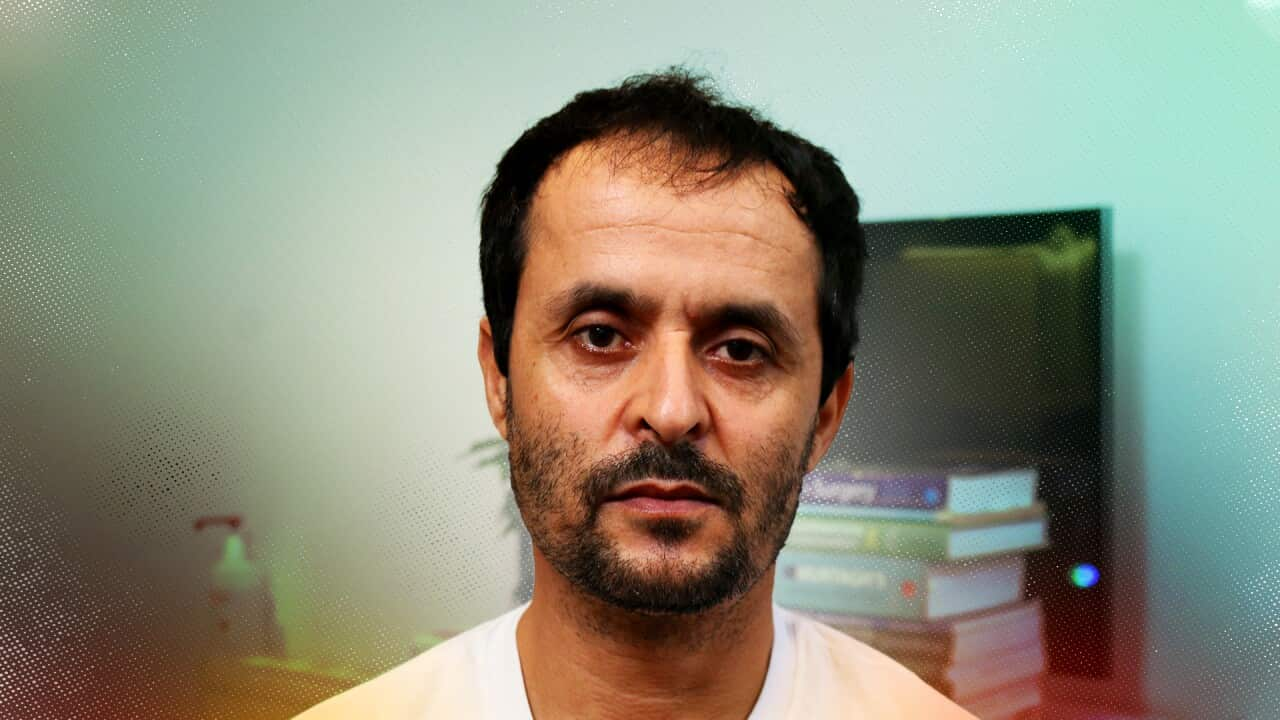

Image: PaYam and Naza fled persecution in Iran and in Australia they rely on charity to get by. (SBS News / Aleisha Orr)

Content warning: This article contains reference to mental health challenges.

PaYam and Naza (not their real names) are a married couple who live in Perth. They might currently call Australia home, but in reality, they exist on the fringes of society looking in.

It’s a sort of shadow existence outside of the realms of what the average Australian would generally experience.

"We’re just living here, sleeping here, walking here – but not like you," Payam says.

And they’re not alone. This is the situation for tens of thousands of people in Australia right now.

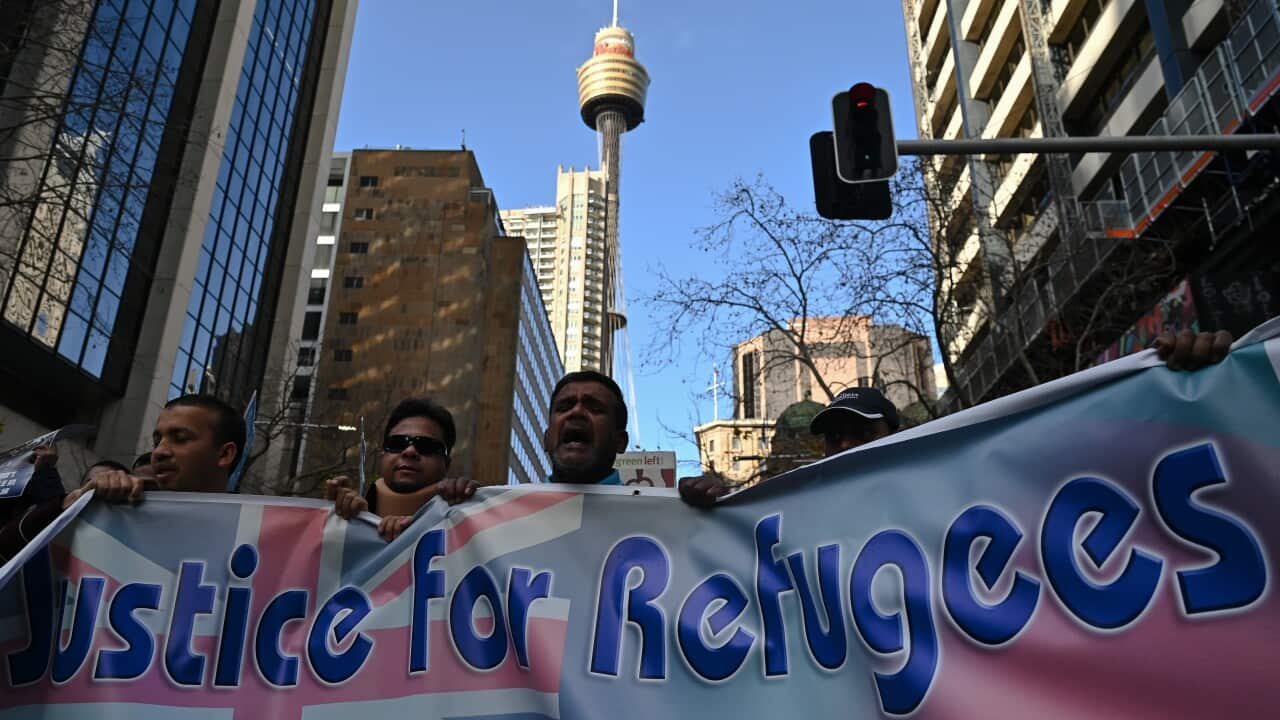

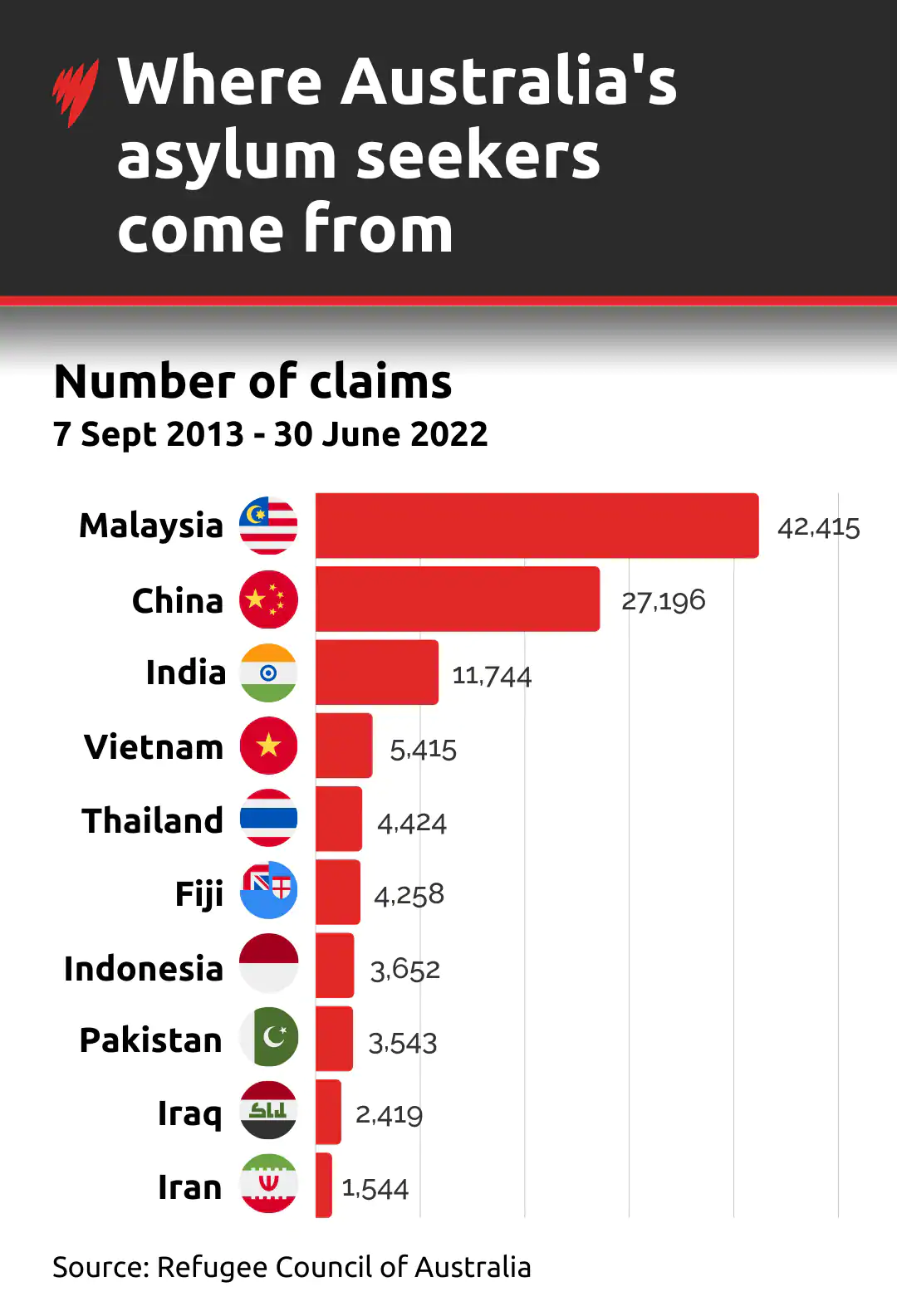

There are more than 70,000 asylum seekers in Australia for whom the federal government is yet to process applications for permanent visas, according to the Refugee Council of Australia. They come from many different parts of the world, including Malaysia, China and India.

Source: SBS News / Leon Wang

PaYam and Naza came here as asylum seekers, escaping persecution in Iran nine years ago. Two of their children, who are now young adults, came with them, and they had a third child after arriving in Australia.

PaYam’s parents fled from Iraq to Iran in the 1970s when a change in the country’s ruler meant they were no longer welcome in Iraq because of their Iranian heritage, but as an adult, PaYam says he was then targeted by authorities in Iran due to his connections to Iraq.

“They now don't recognise people from Iraq in Iran, they don't get allowed to go to school.”

PaYam and Naza fled persecution in Iran. Source: SBS News / Aleisha Orr

Naza, who comes from a Kurdish family, says she also felt unsafe in Iran due to her ethnicity. The Kurdish minority in Iran has long faced injustice and persecution.

But while Australia has offered them safety, they say it’s no life.

PaYam speaks very clearly, making sure the English words he uses are understood.

When he needs to clarify something, he speaks to his case worker in Arabic, and when his wife, whose English is still developing, needs clarification, the two of them converse in Kurdish.

“We’re not living like other people in the community,” PaYam says.

Put simply, they cannot afford to.

The couple came to Australia by boat.

In 2013, Australia adopted a policy that meant , and that policy remains in place today.

The family were in detention for years. Source: Getty / Paula Bronstein

They were then considered to be under community detention, where they were free to move about for the first time.

PaYam and Naza say they used any money they had to get to Australia, so they had no savings to support themselves on arrival.

While on community detention visas, PaYam and Naza each received federal government income support.

Those in community detention are paid at a rate up to 70 per cent of Jobseeker, but people in community detention who also arrived in Australia by boat, such as PaYam and Naza, are only eligible to receive the support at a rate of 60 per cent. For them, that worked out as $21.12 a day each.

PaYam and Naza would not have received this total amount though. While in community detention, asylum seekers do not get a choice about where they live and the federal government provides their housing. A portion of their support payment is withheld to cover utilities.

Source: SBS News / Leon Wang

“This money is small money. [It] is not enough for us but it was better than nothing,” PaYam says.

“We go, for example, to buy the first thing we needed, but we need many, many things.”

Naza, who took responsibility for the family’s spending says a good portion of their payments went towards nappies, baby formula and other items for their youngest child, and what was left over was spent on groceries.

They say were not able to afford a mobile phone between them.

At the end of 2019, after three years of government support, PaYam and Naza, like many others around the same time, were told they would no longer receive payments.

The Asylum Seeker Resource Centre (ASRC), which provides support to asylum seekers in Victoria, says between February 2018 and 2021, funding for social support services (which includes income support) for asylum seekers across the nation was “gutted” with funding dropping from $139.8 million in 2017-2018 to $33 million in 2021-2022.

The Coalition government at the time encouraged asylum seekers who had been given .

Figures from the new Labor government’s latest budget show it has allocated $36.9 million for support payments to asylum seekers. Less than a decade ago, the federal government spent $300 million on such support payments.

In the 2021/22 financial year, the federal government had set aside $33.4 million for the same purpose but spent just under half that amount. The ASRC says the total number of people supported across Australia by the Status Resolution Support Services payment (SRSS) dropped from 13,299 to less than 2,000 in that same period.

At the time, a spokesperson for the Department of Home Affairs said the SRSS was not a social welfare program: "It is designed to provide support for certain non-citizens who are in the Australian community temporarily while their immigration status is being determined".

PaYam and Naza were given four weeks to find a place to live and figure out how they would support their family without access to the social security that Australians, as permanent residents, can access.

Once given the news they would no longer be receiving fortnightly financial support payments, MercyCare, the provider who delivers SRSS services in WA, referred the couple to the Centre for Asylum Seekers, Refugees and Detainees (CARAD).

CARAD is one of about 150 organisations across Australia that step in to assist asylum seekers and refugees with housing, financial help, English classes, education and employment, and social activities thanks to donations from the public and people volunteering their time.

These organisations, which are not supported by government funding, along with other charities throughout communities across the country, support an estimated 10,000 of the 70,000 asylum seekers who are not receiving government support in the country, to meet their basic daily needs.

Volunteers transform the CARAD tearoom in Perth into a food bank. Source: SBS News / Aleisha Orr

In Perth, CARAD’s office tearoom, measuring about four metres by three metres, becomes a food bank twice a week to cater for the 150 or so clients they support.

Groceries are donated by individuals and businesses, as well as food rescue organisation SecondBite.

While the team tries to give their clients autonomy by choosing their own items, and those who donate items have been incredibly generous, the options are minimal when compared to a supermarket.

PaYam and Naza collect groceries from CARAD each week.

In addition, they are also provided with a $100 grocery voucher each fortnight, but with the, that is getting them less and less each week.

PaYam and Naza’s youngest child was born in Australia and attends school but doesn’t see himself as the same as his classmates, they say. CARAD assists the family to get his school uniform but his everyday life is different.

Without any income or financial support, lunch orders aren’t even a one-off special treat, and if there is a school trip that costs money, he does not take part.

On their children's birthdays, PaYam and Naza say there is no party or birthday cake, and invites to other children’s birthdays have to be politely declined as there is no money to spend on presents.

PaYam and Naza say they can't afford birthday parties like their son's classmates. Source: Getty / Nick Bowers

“He says, ‘Dad, why am I different than other people?’”

“It’s hard to answer.”

While paying for a private psychologist is not an option for Naza, who says her mental health deteriorated when in detention, another organisation, Asetts, provides free counselling sessions for her and other asylum seekers.

The family has access to Medicare but without any money coming in, are unable to pay for medication themselves.

CARAD covers the cost of any medication that is prescribed by a doctor but getting it is not as simple as seeing an available doctor and heading to the local chemist.

As CARAD pays for the medication, once they see a bulk billing GP, they then have to take their prescription to the family’s case worker at CARAD, who sends the details to a pharmacy in the Perth CBD that the organisation has an account with, before she heads into that pharmacy to collect the items.

Not all asylum seekers are eligible for Medicare. The Department of Affairs would not say how many of the tens of thousands of asylum seekers in Australia have access to it and instead that need to be met in order to be eligible.

PaYam and Naza’s life is mostly cash free. If the family needs clothing, they tell their case worker who is able to provide vouchers for them to spend at one of St Vincent de Paul’s op shops.

But they do have one asset; a 1994 Toyota Corolla.

The couple say they scraped together $1,000 over three years from the payments they received to buy the vehicle, for which CARAD covers the cost of registration and provides $20 fuel cards for as needed.

The couple owns one luxury; a car they paid $1,000 for (not pictured). Source: Getty / Andrew Merry

The family spends most of their time at home and a train fare to another part of the city is just too expensive, Payam says.

He says he doesn't want to think about what would happen if there was a mechanical problem with the car.

It’s unknown what percentage of asylum seekers in Australia are in the workforce.

While the Department of Home Affairs would not provide details of how many asylum seekers in Australia have been granted work rights, it said departmental officers considered a number of factors when determining the circumstances of visas that they grant.

While the end of the family’s community detention also meant PaYam - who had worked as an electrician in Iran - was given the right to work, a bad back has prevented that.

He says it's from injuries he sustained while in detention and he is awaiting surgery.

Finding work is often difficult for those starting over in Australia. Unrecognised qualifications and English not being your first language are some of the barriers that are faced.

Ms Xamon said many asylum seekers want to work.

“They want the stability of income and because they also want to be able to send money back to their families, usually their dependent children trapped overseas,” she says.

As well as facilitating external work opportunities for asylum seekers, CARAD operates a social enterprise called the Fare Go Food Truck.

CARAD's Fare Go Food Truck. Source: Facebook / CARAD

Research shows the most common occupations among humanitarian migrants are labouring roles.

One of PaYam and Naza’s children has since moved out and now supports themself by working as a cleaner.

Another of the couple's adult children struggles with their mental health. They are socially isolated and unable to leave the house to do things others their age would be doing.

Naza’s mental health has also left her feeling incapable of working at present, she says. What the family has been through is almost too much for her to bear. Her husband translates what she is trying to say:

“I wish to die in the ocean, is better [than] to come to Australia because out in the ocean I will die just one time, but here, day by day second by second, minute by minute [I am dying], you know?”

While PaYam tries to stay strong for his wife and his family, he admits the family’s situation also has him up in the middle of night worrying.

The Refugee Council of Australia has repeatedly said indefinite detention in immigration detention facilities causes significant mental health issues.

Ms Xamon says she’s seen this in the clients that her team at CARAD support: “By the time people get out of detention, actually most of the damage that they have sustained is from their years of indefinite detention”.

Of course, many asylum seekers who have come to Australia have settled well, some with remarkable success stories such as a criminal lawyer who was named NSW Australian of the Year in 2017.

But he has also spoken out about the trauma asylum seekers go through.

“You can’t expect them to get out there and succeed. They need help. They need personal contact. They need psychological assistance, they need counselling. They need support in terms of jobs,” he has previously said.

In September, the federal government indicated it was exploring alternatives to immigration detention, with Minister for Immigration Andrew Giles saying people should be living in the community if there were no safety or security concerns.

PaYam and Naza say they’ve found people in Australia to be very kind. They say they would not have survived without the assistance of CARAD, but they are feeling quite hopeless.

“We are tired,” PaYam says.

He feels “trapped” not being able to improve his family’s situation but knowing they would not be safe in Iran.

“Australian people is very kind people, but they didn’t know what’s happened for us and it’s hard to explain what’s happened for us; I try to protect my family.”

SBS News asked the Department of Home Affairs about financial support provided to asylum seekers in Australia, how eligibility works and about the rate of pay.

A spokesperson for the department said the Australian Government was committed to “generous and flexible Humanitarian and Settlement Programs”.

“The department will continue its long-standing partnerships with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees and countries in our region to address the challenges of providing protection to increasing numbers of displaced people within our region and internationally.”

Figures provided by the department showed it was providing income support to about 1,427 asylum seekers as of the end of July 2022.

SBS News understands eligibility is a matter for government.

PaYam and Naza are currently on bridging visas, which last for six months at a time. They are part of a group of about 31,000 asylum seekers who the federal government refers to as the ‘unauthorised maritime arrival legal caseload’.

As it stands, Australia will not process their asylum claims which could recognise them as refugees. Instead, the government has been insisting the thousands of people in this situation resettle in New Zealand or the United States.

The government indicated last month that 19,000 asylum seekers on temporary protection visas and safe haven enterprise visas will be allowed to stay permanently in Australia from early 2023. They will be granted rights to social security and reunion with family members, The Guardian reported.

A decision on a further 12,000 people on bridging visas, such as PaYam and Naza, is yet to be made.

Ms Xamon says, “at the end of the day we have to recognise the very reason our clients are here is because they have nowhere else to go, that is the very nature of being a refugee”.

Readers seeking crisis support can contact Lifeline on 13 11 14, the Suicide Call Back Service on 1300 659 467 and Kids Helpline on 1800 55 1800 (for young people aged up to 25). More information and support with mental health is available at and on 1300 22 4636.

supports people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds.