Our atoll nation is barely two metres above sea level, and the waters are coming for us.

Despite the progress and momentum of the COP26 climate conference in Glasgow, we are still not moving fast enough to avoid the worst of climate change.

It is heartening that more than 190 countries and organisations agreed to rapidly phase out coal power and end support for new coal power stations. More than 100 countries signed a pledge to cut methane emissions 30 per cent by the end of the decade, and about the same number agreed to stop deforestation on an industrial scale in the same timeframe.

But even with these agreements, we in Kiribati face the death of our homeland. Co-author Anote Tong led our country as president for 15 years, alongside lead author Akka Rimon, who was foreign secretary between 2014 and 2016. The problem is speed. Our land is than global action can stem climate change. Delays and a lack of global leadership mean the existence of small island states like Kiribati is now in the balance.

The problem is speed. Our land is than global action can stem climate change. Delays and a lack of global leadership mean the existence of small island states like Kiribati is now in the balance.

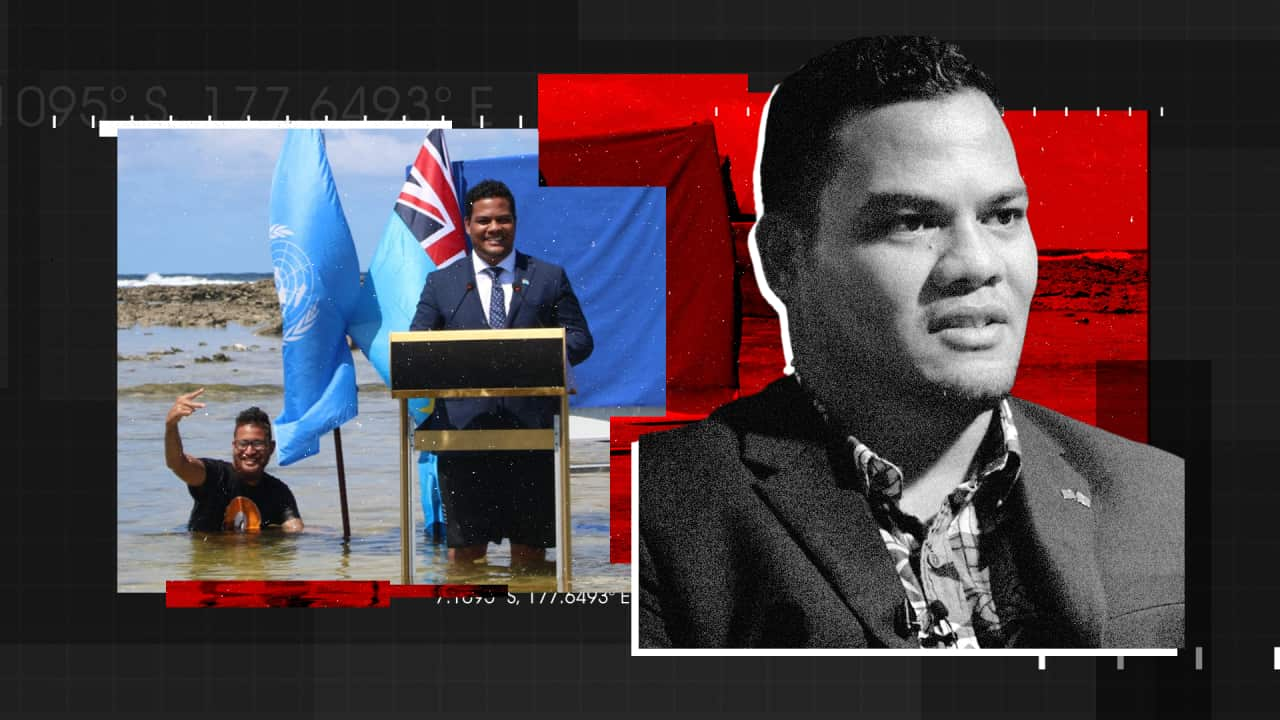

Author Anote Tong, when he was Kiribati president, at the Pacific Islands Forum in 2015. Source: AAP

That means we must urgently find ways to rehome our people. It is very difficult to leave our homes, but there is no choice. Time is not on our side. We must prepare for a difficult future.

What we need is a model where displaced people can migrate to host nations when their homes become uninhabitable. Countries like Australia need workers – and we will soon need homes.

This is, increasingly, a question of justice. Australia’s actions, in particular, raise questions over how sincere it is in honouring its recent commitments at COP26.

As the world’s of liquefied natural gas and the second-largest exporter of coal, Australia’s reluctance to change is putting its neighbours in the Pacific at risk of literally disappearing. It is the only developed nation not committed to cut emissions at least in half by 2030.

In Glasgow, Fiji urged Australia to take real action by halving emissions by 2030. Did it work? No. Australia also refused to sign the agreements on ending coal’s reign, with prominent politicians undermining the COP26 agreement as soon as the conference was over.

We desperately hope the commitments Australia did make at COP26 are not just words on paper. But if they are, that makes our need for certainty even more urgent.

Let us speak plainly: If Australia really does plan to sell as much of its fossil fuel reserves as possible and drag its feet on climate action, the least it can do is help us survive the rising seas caused by the burning of its coal and gas.

Eighteen years ago, the Kiribati government – then headed by Anote Tong – introduced a as a way for I-Kiribati people to adapt to climate change.

We gave our I-Kiribati workers international qualifications tailored for jobs in demand overseas. After this, Kiribati, Tuvalu, Fiji, Tonga and New Zealand to allow workers to migrate to New Zealand if they had an offer of a job. Each year prior to COVID, 75 people from Kiribati were able to migrate through the scheme.

New Zealand is the first and only country currently offering a permanent labour migration program from Kiribati. While welcome, we will need more places for I-Kiribati as climate change intensifies.

Like New Zealand, Australia has expanded its seasonal worker schemes for Pacific workers, and is now moving towards a longer stay, multi-visa arrangement under its . We expect this scheme will evolve into a permanent migration scheme similar to New Zealand.

While we wait in hope for a true safe haven for our people, our diaspora is growing. I-Kiribati are moving now to Pacific countries higher above the water level such as Fiji, the Cook Islands, Niue, Samoa and Tonga.

Are we scared? Of course. We are on the front line of this crisis, despite having done amongst the least to cause it. It is difficult to leave the only home we have known. But science does not lie. And we can see the water coming.

Labour migration will not solve climate change, but it offers hope to those of us who will be displaced first.

This is a vital question of climate justice. This upheaval is caused by high-emitting economic powerhouses like the US, China, and the European Union. But the vulnerable are paying the full cost. That is not fair.

As climate change worsens, other global leaders must consider how best to support adaptation through labour mobility. Far better to plan for this now than to let climate change rage unchecked and trigger ever-larger waves of refugees.

The people of Kiribati are under pressure to relocate due to sea level rise. Source: Getty Images

The question of climate justice

Consider this: in 2018, each person in Kiribati was responsible for 0.95 tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent. By contrast, each person in the United States was . Despite this imbalance, the US has taken little responsibility for what is happening to Kiribati and other low-lying nations.

We are hopeful this may change, given US President Joe Biden recently pledged to make his nation a leader in climate finance by supporting nations worst hit by climate change and with the least resources to cope. It’s also encouraging that new laws have been proposed to allow people displaced by climate change to live in America.

We must work to slash emissions and devise solutions for the problems caused by the warming.

International law must recognise climate displaced populations and create ways we can be rehoused.

While other solutions such as climate-proofing infrastructure or even floating islands have been proposed for Kiribati, these cannot happen overnight and are very expensive. By contrast, labour mobility is fast and advantageous to the host country.

Kiribati’s current government is working to increase skills and employability in our workforce. We are doing our part to get ready for the great dislocation.

When I-Kiribati have to migrate, we want them to be able to do so as first-class citizens with access to secure futures rather than as climate refugees.

We are doing all we can to stay afloat in the years of ever angrier climate change. But it will take the global village to save our small village and keep alive our culture, language, heritage, spirits, land, waters and above all, our people.

Akka Rimon is the former foreign secretary of Kiribati and a PhD student at the Australian National University. She is currently employed by the World Bank. The views expressed in this piece are hers and in no way represent the views of the bank.

Anote Tong is the former president of Kiribati and distinguished global leader-in-residence at the University of Pennsylvania. He does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Correction: an earlier version of this story stated Australia was the largest exporter of fossil gas in the world. It is the largest exporter of liquefied natural gas.