Key Points

- The NSW police commissioner has faced backlash for describing an alleged double murder as a "crime of passion".

- Webb has since clarified she was distinguishing the type of crime as one of "domestic nature".

- Advocates against domestic violence say the term's use is "irresponsible", stressing the importance of language.

This article contains references to domestic violence.

The NSW police commissioner has faced backlash for describing a recent high-profile alleged double murder as a "crime of passion".

Karen Webb has since clarified the remarks, explaining she intended to distinguish the motive from a gay hate crime to one of a "domestic nature".

"It is a crime. And I qualified that by saying it's of a domestic and stalking nature and we allege two murders," she told reporters on Tuesday.

"So I again say my apologies, if that word upset people, and it wasn't intended that way, it was intended to distinguish it from a gay hate crime."

However, experts argue the comments highlight an important flaw in our language. So why is the use of this term creating a stir?

What is a 'crime of passion' and its use as a legal defence?

A crime of passion is a common phrase used interchangeably with the legal term "heat of passion".

During a murder trial, the defence can make the case that a person's actions were in response to extreme provocation under legislation first introduced in 1873.

The NSW Crimes Act states if extreme provocation is established the person will be convicted of manslaughter not murder, resulting in shorter maximum prison penalties.

Why do domestic violence advocates object so strongly to this term?

Advocates against domestic, family or intimate partner violence argue the use of the term romanticises and minimises the seriousness of the crime.

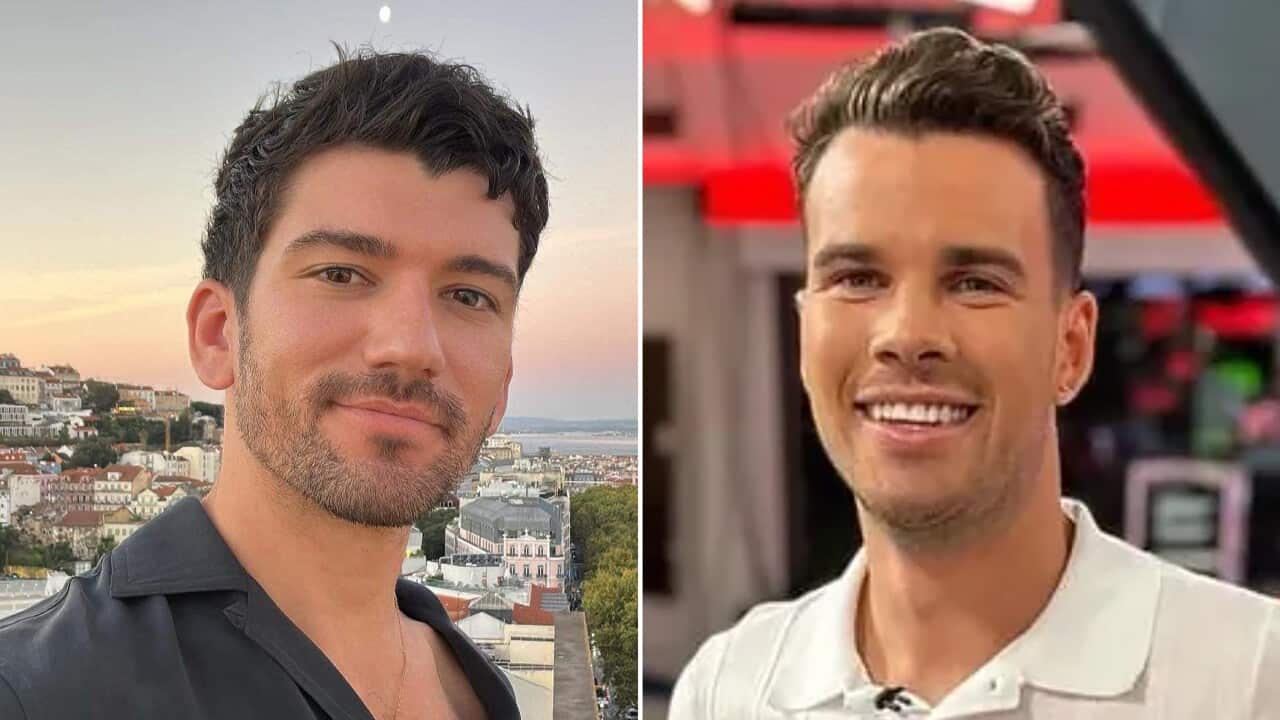

LGBTQ Domestic Violence Awareness Foundation founder and managing director Ben Bjarnesen said associating these crimes with passionate acts is "irresponsible".

"Using this term minimises the seriousness of this violent crime, which is what domestic violence is — in this circumstance, a murder has been committed — and there's no provocation or justification for that," he told SBS News.

"To talk about this as a crime of passion detracts from the horrific crime that has occurred … Violence is a choice, and is never the answer.

"No crime like this should ever be associated with an act of love or an act of affection."

Every year, around 20 per cent of homicide victims are killed by an intimate partner, according to Australia's National Research Organisation for Women's Safety (ANROWS).

Bianca Fileborn, associate professor in criminology at Melbourne University, agrees the label completely misrepresents the "lethal nature" as well as the causes of intimate partner violence.

"That's really not actually based on what we know about particularly men's use of violence in intimate relationships, which this violence is about power and it's about control of the person," she said.

Fileborn said the violent acts point to a wider pattern, including a sense of entitlement over another person, and were often driven by power inequalities.

Language matters, with high DV rates in LGBTIQ+ community

ANROWS CEO Tessa Boyd-Caine said language is important, especially to those experiencing violence in the community.

"Without assuming what's happened in this case, the risk of language like a crime of passion is that it leads to excusing or even forgiving acts of violence because they occur in an intimate partner context or in a family dynamic," she told SBS News.

"And so that makes the community worry that some types of violence are not being taken as seriously as other types of violence."

She said these concerns can be heightened when used by people in the justice system, as they are perceived as the authority to investigate and hold people to account.

More than 60 per cent of LGBTIQ+ people have experienced intimate partner and abuse in their lifetime, according to the 2020 La Trobe University Private Lives Report.

Boyd-Caine said the LGBTIQ+ community already faces stigma or harassment that undermines feelings of safety, with the risk of experiencing violence compounded if support from family members is lacking.

"I think we need our police, we need everyone to be understanding how serious … violence that occurs in the home or in the context of a relationship is," she said.

"It's just as important as any other form of violence that they need to be policing."

If you or someone you know is impacted by family and domestic violence, call 1800RESPECT on 1800 737 732, text 0458 737 732, or visit . In an emergency, call 000.

LGBTIQ+ Australians seeking support with mental health can contact QLife on 1800 184 527 or visit . also has a list of support services.