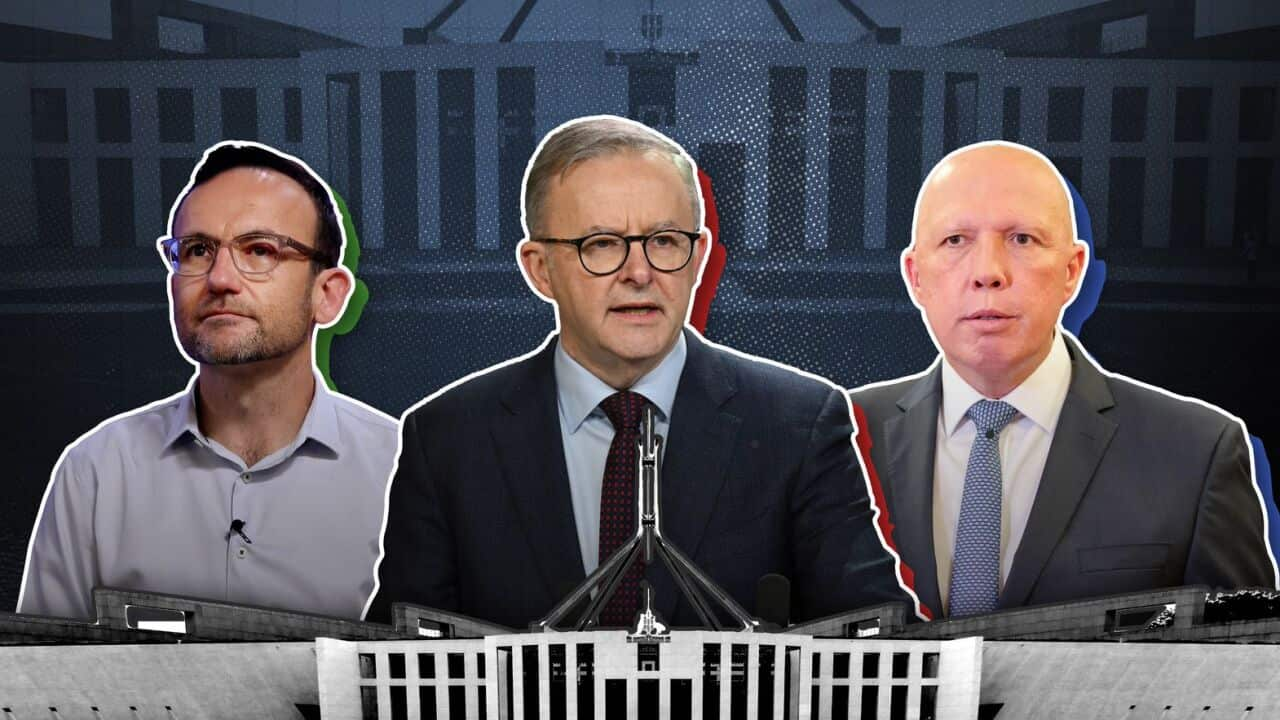

Prime Minister Anthony Albanese wants to "end the climate wars" but his plan to enshrine action on climate change will be tested as federal parliament returns on Tuesday.

The first sitting week under his new government begins with Mr Albanese signalling he wants a new era of respect in Canberra, as he pushes ahead with his legislative agenda to secure reforms promised at the election.

The climate change bill has been named as a top priority, but the plan to legislate a 43 per cent emissions reduction target is set to present an early challenge at the negotiating table facing calls for more ambition, and opposition from the Coalition.

Why does Labor want to change the emissions target?

Labor has maintained enshrining the response is "best practice" to provide certainty to businesses, investors and the community over the energy transition.

Climate Change and Energy Minister Chris Bowen said the government was acting on its commitment to Australians.

"We went to the election promising to reduce emissions by 43 per cent by 2030, we were given a mandate and now we are delivering," he said.

"This bill makes it clear that 43 per cent is our minimum commitment - and does not prevent our collective efforts delivering even stronger reductions."

Climate Change and Energy Minister Chris Bowen addresses the National Press Club in Canberra. Source: AAP / BIANCA DE MARCHI/AAPIMAGE

It also tasks the independent Climate Change Authority to provide advice on Australia's progress against its targets, and also advise on a 2035 target.

The laws would require the minister for climate change to report annually to parliament on the progress of meeting targets.

The task ahead is to try to achieve some form of political consensus over the proposal in the policy area that has long been defined by political divisions in Australia.

Why did Labor choose the target?

The plan to cut emissions by 43 per cent by 2030 on 2005 levels, and net zero by 2050, dates back to Labor's pledge made ahead of the federal election in December last year.

The announcement - at the time highly anticipated - came after Labor’s loss at the 2019 federal election, where the party had taken a 45 per cent medium-term target.

The government says it was reached by determining policy settings required to secure a pathway to reaching net zero by 2050, rather than starting with an intended target.

That would include a plan to increase the share of renewables in the National Electricity Market to 82 per cent by 2030.

The target of the former government under Scott Morrison was a 26 to 28 per cent cut to emissions by 2030, but had forecast emissions to fall by 30-35 per cent.

The new government has already formally committed Australia to lifted targets under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change's binding Paris Agreement.

What obstacles does the government face?

The government has a majority in the House of Representatives meaning it can pass the bill there, despite facing calls from Greens and independent MPs for more ambitious targets.

But it's a different story in the Senate - there it holds 26 seats compared to the Coalition’s 32 seats.

This means Labor would need the support of the Greens to pass the legislation, and at least one more vote.

The Greens - who now have 12 senators - have expressed concern the bill in its current form would place a floor or ceiling on reduction targets.

It’s also expressed fears the legislation wouldn’t compel specific action that hold the government to account, like preventing new coal and gas projects from being built.

Greens leader Adam Bandt on Monday said his preference was to improve and pass the legislation, but he continued to hold concerns.

“We’re approaching these discussions in good faith,” he said.

The Coalition has said it supports reducing emissions, but locking in a target would be a mistake because it would remove flexibility if the energy supply environment suddenly changes, instead calling for a focus on investment in technology.

The crossbench is made up of two One Nation senators, two from the Jacqui Lambie Network, independent David Pocock and also one seat for the United Australia Party.

Both Senator Pocock and Senator Lambie have expressed openness to supporting the legislation.

What are other countries doing?

Labor's commitment follows action from other countries to adopt emissions targets into law, to demonstrate a firm commitment to reaching them.

But it’s also not clear how the legally binding nature of these targets would be enforced if a government failed to meet them, but the targets are seen as a signal both within the countries themselves and to the world of a commitment.

The United Kingdom has legislated the most ambitious target in the world to slash emissions by 78 per cent by 2035 compared to 1990 levels.

Japan, Canada, the European Union, Sweden, Germany, France, Denmark, Spain, Hungary and Luxembourg and New Zealand also have legislated net zero commitments.

On the higher end, Sweden intends to reduce emissions 63 per cent by 2030, Denmark 70 per cent by 2030, Germany has also committed to at least 55 per cent by 2030.

Meanwhile, Japan intends to reduce emissions 46 per cent by 2030, Canada 40-45 per cent by 2030 and New Zealand has pledged a 50 per cent cut.

Will Labor be willing to negotiate?

Mr Albanese has remained adamant there will be no shift on the 43 per cent emissions reduction target describing it as a promise to the Australian people.

But he has expressed a willingness to considering any “sensible amendments” that were proposed as a way of improving the legislation.

Senator Pocock said he had held “good discussions” with the government over the climate bill.

“I’m committed to being constructive and my sense is there is an expectation in the community that we do legislate something,” he told SBS News.

“We have to move past the uncertainty and actually have a target and have one where we can ramp up the ambition over time.”

Independent senator David Pocock at a press conference at Parliament House in Canberra. Source: AAP / MICK TSIKAS/AAPIMAGE

What have experts said about the environment?

The climate bill's introduction to parliament comes after a long-awaited government report detailed Australia's failure to protect natural environments and threatened species.

The State of the Environment report - a mandatory assessment prepared by a panel of independent scientists every five years - described the “poor and deteriorating” decline facing the environment as a result of “all aspects” of the Australian environment being under pressure.

There is pressure from abroad too, as COP26 president Alok Sharma has described the commitment as a “great start”, but encouraged the government to go further.

“The 43 per cent is good, it provides for further ambition in the future and I want to see that from every country,” he told reporters on Monday.

The Climate Council has recommended that Australia cut its emissions by 75 per cent (based on 2005 levels) by 2030 to pursue efforts to limit warming to 1.5C.