“Given the way Me Too has developed in the last few months, I argue this could be the most transformative social movement in China since 1989’s democracy movement,” Dr Leta Hong Fincher tells SBS News.

It’s a big call for a social media hashtag that initially struggled to gain traction in the country, and has since had to work hard to evade the censors. And it’s an even bigger call to compare it with a movement that resulted in the Tiananmen Square massacre.

But Dr Fincher, the author of two books on the Chinese women’s movement and the first American to gain a PhD from Beijing’s Tsinghua University, said #MeToo is different because it has reached millions of ordinary women across China.

“You have to understand how difficult it is to get a hashtag campaign going in China on an issue that’s seen as politically sensitive by the government. You just haven’t seen anything this widespread and vibrant, where young people are so enthusiastic and committed and passionate about a cause,” she said.

Women look at their smartphones in Xintiandi district, Shanghai. Source: AFP / Getty Images

“It’s in so many Chinese cities and it’s also spread beyond university campuses to factories, it’s blending in with the labour rights movement, with working-class women on the front lines of protests.”

“It involves so many ordinary people rather than just hard-core political activists.”

This week marks one year since The New York Times first published sexual harassment allegations against Harvey Weinstein, spurring the hashtag. There have since been scalps of alleged abusers and harassers in China who have been claimed by the movement.

In August, after allegations he forced nuns to have sex with him.

But not everyone shares Dr Fincher’s optimism about the momentum of the women’s movement.

“I think it has grown in a way that is very precarious,” Dr Denise Tse-Shang Tang, an assistant professor researching gender and sexuality at Lingnan University in Hong Kong, told SBS News.

“It’s very difficult for them to organise online nowadays … It’s been difficult,” said the professor, who will lead a discussion on #MeToo and China at Monash University in Melbourne on 4 October.

From #MeToo to #RiceBunny

In January this year, when a US-based Chinese software engineer named Luo Xixi wrote about her frightening experience of sexual harassment at the hands of her former professor at Beijing’s Beihang University, #MeToo went viral in the country of nearly 1.4 billion.

The hashtag collected 4.5 million hits on Chinese social media site Weibo in the first month, according to The Atlantic. The university investigated (although they had previously refused to before Ms Luo made her complaint public) and the professor was sacked.

The issue of professors forcing themselves on students struck a chord – within weeks there were more than 70 open letters with hundreds of signatures circulating on social media that called for action to prevent sexual harassment on campuses – although some petitions were quickly deleted by censors. A male professor at Wuhan University named Xu Kaibin published signed by at least 50 professors from 30 colleges.

“It seized on the global momentum of Me Too, but what’s happening in China is very much home-grown,” Dr Fincher said.

State media coverage of the developments was selective. After initial signs of support for the hashtag, the government soon started censoring it. To get around this, Chinese women began using the hashtag ‘rice bunny’ or emojis of a bowl of rice and a rabbit to continue the campaign. In Mandarin, rice is pronounced ‘mi’ and bunny, ‘tu’.

A sign used to protest sexual harassment posted on Weibo. Source: The Conversation

Dr Tang said the Chinese government is wary of any grassroots movement on social media, whatever the merits of the cause.

“It’s the idea of mobilising, the idea that you can do that online easily now,” Dr Tang said. “You’re talking about now being able to call on the experience of many, many women across provinces, across classes, talking about this issue. That would be very upsetting and disturbing to the Chinese government, not only the issue itself but the ability to organise and mobilise without state approval.”

And there has been pushback, with China’s first #MeToo case now to set for the courts after a former intern accused a famous TV host of forcibly groping her. The BBC reports that the TV star, Zhu Jun, denies the claims and , who has said she will countersue in court.

The feminist five

A new generation of feminist activists prepared the ground for #metoo to take off in China, Dr Tang said.

“2012 to 2015 was the boom era for young feminists in China, who are very social media savvy,” she said.

Provoked by a campaign by the Shanghai Subway Corporation that blamed the way women dressed for harassment, young activists started doing performance art style street protests, first in Shanghai and then in other cities.

Later came prominent activists from around China who were jailed for simply planning to hand out stickers about sexual harassment on public transport on International Women’s Day. Many of them had earlier been involved in high-profile theatrical protests such as to raise awareness of China’s domestic violence problem.

“There was this huge global outcry over the jailing of these young women,” said Dr Fincher. “The authorities were thinking they would be able to crush a potentially large-scale feminist movement by jailing them. But it drastically backfired because it served to galvanise the feminist community inside China.”

Following wide condemnation, the women were released after more than a month in jail.

Censorship vs change

Three years later, the Women’s Federation in Beijing has just put up signs against sexual harassment in the subways – something the feminist five were jailed for trying to campaign for. Some of the powerful men publicly accused of sexual abuse or harassment in academia, business and the creative industries have lost their jobs. And there is also a move to create a new offence of sexual harassment in workplaces in the civil code, although Dr Tang said scholars have criticised the vague terms of the draft provision.

But censorship remains.

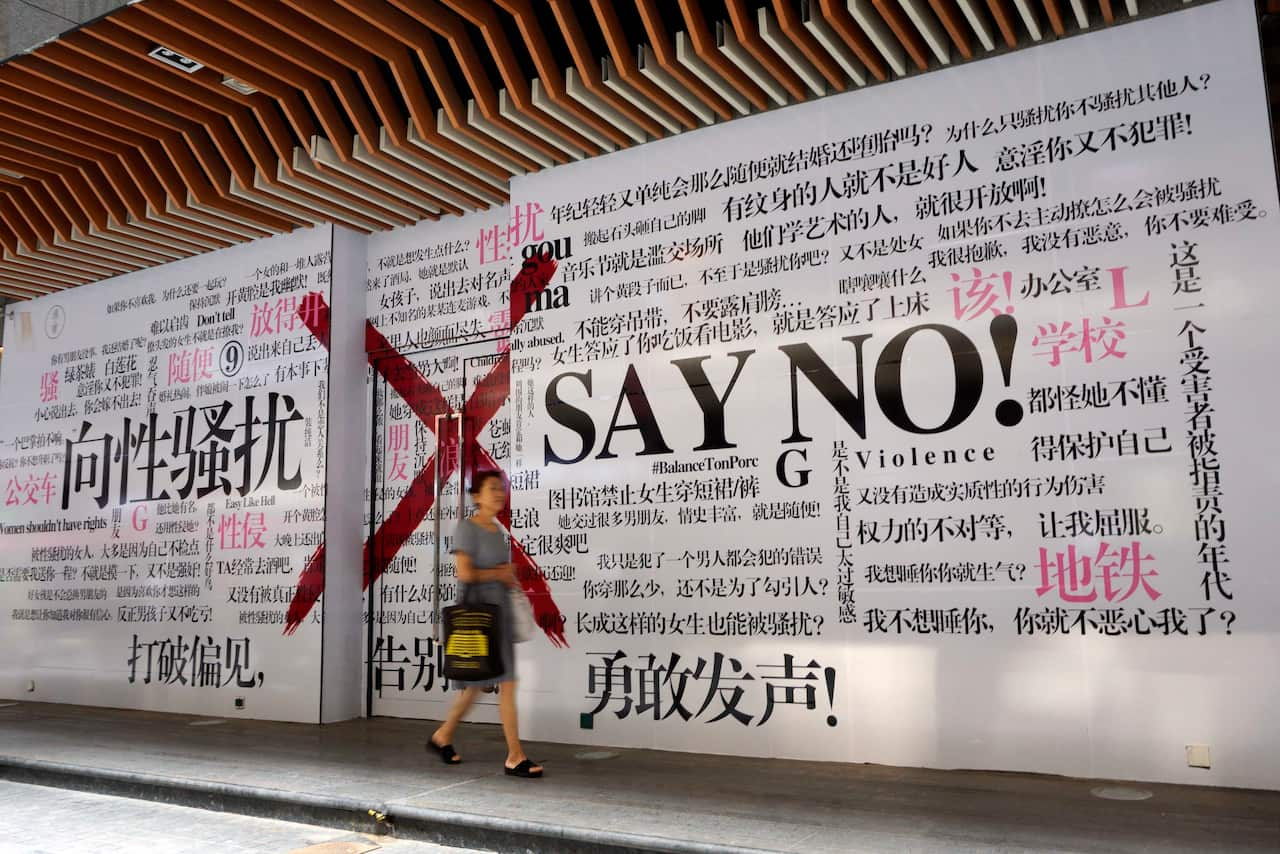

A poster that reads 'say no to sexual harassment' and encourages women to speak out, on a wall in Xi'an, Shaanxi Province. Source: Visual China Group / Getty Images

A prominent feminist group, the Beijing-based Feminist Voices, which had 180,000 members online, fell foul of government censors and was removed from the Weibo and Wechat networks earlier this year for “posting content that violated regulations”. And repeated waves of censorship of feminism and related sensitive terms on social media has made it very hard for activists to organise.

Dr Tang doesn’t think the women’s movement will be successfully silenced despite the tightening political control in the past three years.

“It’s hard to imagine it will go away. I think it’s hard to stop it, you hear of new [Me Too] incidents every few weeks. So I think the public, in general, are aware of these issues now in China.

“It’s about finding ways to work around it. That’s what a lot of women’s rights activist are trying to navigate.”