11 min read

This article is more than 2 years old

How COVID took over the world and (eventually) Australia

It's been three years since an unknown virus was detected in China and went on to change the world as we know it. Here's a timeline of what happened and two animated maps showing how cases spread.

Published 31 December 2022 8:39am

By Charis Chang, Ken Macleod

Source: SBS News

On 31 December 2019, China reported a cluster of pneumonia cases in the city of Wuhan with an unknown cause. It was later identified as a novel coronavirus.

In Australia, the first COVID-19 case was confirmed on 25 January 2020, but it was largely overshadowed by the ferocious Black Summer bushfires that shrouded Sydney in smoke and burnt large parts of NSW and Victoria.

It seemed that Australia had only just dealt with one crisis when another emerged, with growing unease about the spread of a mysterious virus around the world.

On 30 January 2020, the World Health Organisation declared the outbreak a Public Health Emergency of International Concern and on 11 March 2020, it declared COVID-19 a pandemic.

The animation below shows what happened next (the red bubbles represent reported COVID-19 cases).

From 1 February 2020, the federal government imposed travel restrictions and quarantine requirements on people arriving from China, and in the following days two groups of Australians arriving from Wuhan were quarantined on Christmas Island (where an immigration detention centre formerly housed asylum seekers) and at Howard Springs near Darwin.

On 10 March 2020, Health Minister Greg Hunt announced there were 100 confirmed cases of COVID-19 in Australia.

On 11 March 2020, the federal government announced a $2.4 billion health package to address COVID-19. The package included $1.1 billion for personal protective equipment (PPE) for patients and critical healthcare staff and antibiotics and antivirals for the National Medical Stockpile, and $500 million for states and territories for their COVID-19 response.

On 12 March 2020, the government announced a $17.6 billion economic support package (followed later in the month with a $66 billion support package) and on 13 March 2020, National Cabinet was formed. Made up of the Prime Minister, premiers and chief ministers, it would then meet weekly to address Australia's response to the pandemic.

On 18 March 2020, National Cabinet announced a range of measures, including bans on non-essential indoor gatherings of more than 100 people and the cancelling of Anzac Day ceremonies.

On 20 March 2020, Australia was one of the first countries in the world to .

It was at this point many Australians began to take notice of what was going on, and supermarket shelves were stripped as panic buying began.

Empty toilet paper shelves in Coles. Source: SBS News / SBS News

States and territories soon brought in a range of emergency measures and by the end of March many non-essential businesses had been forced to close and social distancing measures had been introduced. Victoria and NSW banned large gatherings and also sent their residents into lockdown.

Around the same time, millions of people were advised to work from home if possible, and to only leave their residences for groceries, exercise and other essential items. Schools in many states were closed with parents asked to keep their children at home.

States including South Australia, Queensland, Western Australia and Tasmania closed their borders, requiring travellers to quarantine for 14 days. Movement into Indigenous communities was also restricted.

The ban on international travel meant thousands of temporary visa holders were stuck in Australia, unable to return to their home countries to see family and friends because they wouldn't be able to re-enter. Many were also .

The months-long restrictions and lockdowns were effective and kept case numbers relatively low.

Vaccines were developed and by 20 October 2021, 70 per cent of Australians had received two vaccine doses. This was seen as a key milestone in allowing restrictions to be eased, and they were.

But later in the year, the new Omicron variant started to take hold. By December 2021, it was spreading rapidly across the country.

The animation below shows how COVID-19 cases took hold in Australia.

Why COVID-19 caused a major global crisis

The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare's report on the first year of COVID-19 in Australia noted there were a number of factors why the virus had such a significant worldwide impact.

COVID-19 was caused by a virus not previously seen in humans, there was no immunity in the population, and no specific vaccine or treatment that could be used to treat it.

The disease was also highly infectious and impacted some people severely. It could be spread by people who were not very ill because the peak infectious period appeared to be before, or just after, symptoms developed, enabling it to spread in the community "under the radar".

Scientists developed vaccines for COVID-19 in record time with AstraZeneca's jab one of the first to be approved for use in Australia on 15 February 2021. Credit: AstraZeneca

The popularity of international travel also helped the virus spread quickly around the world, especially in places like Italy and other parts of Europe, before spreading further.

The rise of different variants

There have been a number of COVID-19 waves in Australia and in recent times these have been driven by the discovery of new variants. By the start of December 2021, five variants of concern had been detected in Australia: Alpha, Beta, Gamma, Delta and Omicron.

The first wave of cases in Australia were mainly linked to the return of overseas travellers, including those who had been on cruise ships, and impacted most states and territories, although case numbers were fairly modest.

The second wave of cases in Victoria - between May and September 2020 - was driven largely by an outbreak in its hotel quarantine system, which saw Melbourne residents locked down for almost four months in what some say was the .

Melbourne residents were in lockdown for 263 days. Source: Getty / Getty Images AsiaPac

By June 2021, the Delta strain, first detected in India between December 2020 and February 2021, had started to circulate in the harbour city. A limousine driver unknowingly become patient zero of a new outbreak that would see parts of Sydney locked down for three and a half months.

The Delta variant would also spread to other areas, with most capital cities in Australia locked down in early July 2021.

The rise of an even more infectious variant, Omicron, later created chaos for people over the Christmas-New Year period with and a , causing stress for many Australians, especially those wanting to travel and reconnect with friends and relatives in other states.

Omicron, first detected in South Africa and Botswana in early November 2021, has continued to drive large numbers of infections in the community but its impact has been less severe because of widespread vaccination and generally mild symptoms.

A "variant soup" of new Omicron sub-variants has since caused a spike in infections prior to Christmas including the XBF recombinant strain (a combination of BA.2.75 and BA.5) as well as XBB recombinant.

The impact of the vaccine

Australia managed to secure access to new vaccines that started to be rolled out in 2021.

While vaccine distribution was initially slow, it then gathered pace with most of the population getting access to at least one shot by the end of that year.

By 30 April 2022, Australia had one of the highest vaccination rates in the world with 83 per cent of the total population receiving two doses.

COVID-19 testing at Bondi in Sydney. Source: AAP

The development of vaccines in record time has helped to keep death rates down, with a UK Health Security Agency report released on 1 December showing the vaccines were 85 per cent effective against deaths from Omicron two to four weeks after a third dose, and 68 per cent effective even after six months.

Vaccination rates have been lower among Indigenous Australians, residents of the Northern Territory and participants in the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS).

Overall, Australia's response to COVID-19 has led to some of the best health outcomes in the world.

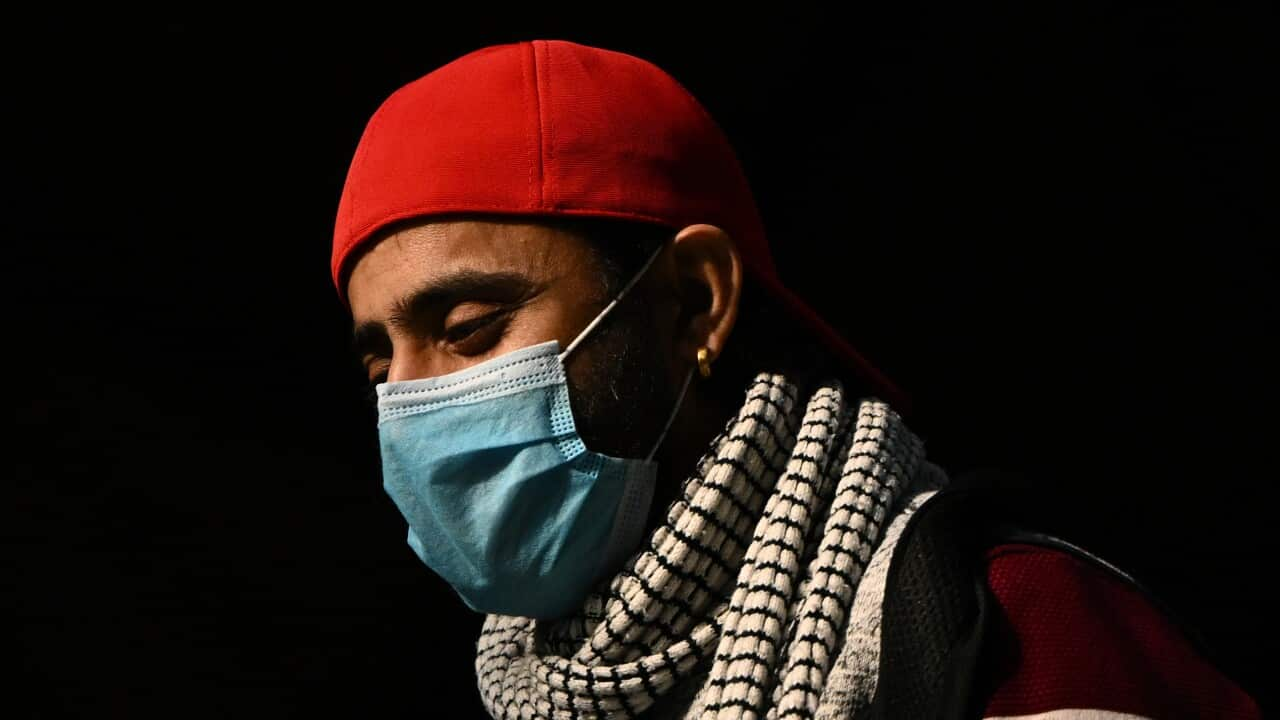

This has been attributed to Australia's decision to close its borders early, lockdowns, physical distancing, mask mandates, quarantine and isolation rules. COVID-19 patients also have access to oral treatments such as molnupirovar and nirmatrelavir + ritonavir.

Up until early October 2021, Australia had the second-lowest total number of confirmed cases per capita of all Organisation of Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries. Only New Zealand had a lower rate. Australia also had the third lowest death rate after South Korea and New Zealand, the most recent AIHW report noted.

By early March 2022, Australia had dropped to the eighth-lowest rate of confirmed cases, and the fifth-lowest death rate, largely due to the increase in cases from the Omicron outbreaks.

Among those deaths registered by 31 March 2022, people from lower socioeconomic groups and those born overseas, particularly in North Africa and the Middle East, had higher COVID-19 mortality rates.

Antibody studies have found around 65 per cent of adults in Australia had got COVID-19 by the end of August 2022. The infection rates in young people aged 18-29 years old were much higher, at 80 per cent, with rates gradually decreasing with age to 42 per cent among those over 70.

Queen Elizabeth II sits alone at Prince Philip's funeral on 17 April 2021. Source: Getty / WPA Pool/Getty Images

In the 18 months that followed, this grew to more than 8,000 deaths in Australia.

Up until 30 June this year, 8,219 people had died with or from COVID-19, making up 2.1 per cent of deaths during the pandemic.

COVID-19 was the underlying cause of death for 85.9 per cent of these people. Another 1,162 people died of other causes such as cancer but COVID-19 was thought to have contributed to their death.

The median age for those who died with COVID-19 was 84.7 years (82.9 years for men, 86.7 years for women). Chronic cardiac conditions were the most common pre-existing chronic condition. About 60 deaths were due to long-term effects of COVID-19, including .

The latest ABS figures show by 30 September 2022, 12,545 people had died with or from COVID-19 in Australia.

As of 23 December 2022, there had been 6,656,601 deaths around the world, according to the World Health Organization.

Among OECD countries, Hungary had the highest official death rate from COVID-19 as of 20 December 2022, according to Our World in Data. It was followed by the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Lithuania, Greece, Latvia, Slovenia and the United States. Australia had the fifth lowest rate and Japan had the lowest rate, followed by New Zealand, South Korea and Iceland.

The World Health Organisation raised people's hopes in September 2022 when its director-general said .

"Last week, the number of weekly reported deaths from COVID-19 was the lowest since March 2020," Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said during a news briefing.

"We have never been in a better position to end the pandemic. We're not there yet, but the end is in sight."

Would you like to share your story with SBS News? Email