Key Points

- A three-day gathering on Dunghutti country in NSW will mark 100 years since the opening of the Kinchela Boys Home.

- The government forcibly removed boys aged five to 15 from their families and sent them to Kinchela.

- Survivors and their descendents travelled back to the site to remember the past and celebrate their resilience.

A group of First Nations men boarded a train from Central Station this week, embarking on an emotional seven-and-a-half-hour journey that retraced a painful past.

The men were survivors or descendants of survivors travelling back to the site of the notorious Kinchela Boys Home in Dunghutti, country, on the mid-north coast of NSW.

At the other end of the train line was a three-day gathering marking 100 years since the opening of the home, at which attendees would remember the past and celebrate their resilience.

They said the event would be a significant moment of truth-telling, at which stories of survival and strength — as well as hopes for the future — would be shared.

'In the interest of the moral or physical welfare'

The Kinchela Aboriginal Boys Training Home was run by the NSW government for over 50 years, from the 1920s to the 1970s.

Under the guide of the so-called Aborigines Protection Act of 1909, the government forcibly removed boys aged five to 15 from their families and sent them to Kinchela if their removal was determined to be, as they stated, "in the interest of the moral or physical welfare".

In 2018, the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare found there were 17,000 survivors of the Stolen Generations still alive in Australia, and The Healing Foundation estimates more than a third of all First Nations Australians are descendants of survivors.

Uncle Bobby Young, one of those who boarded the train, said he had mixed feelings about the return.

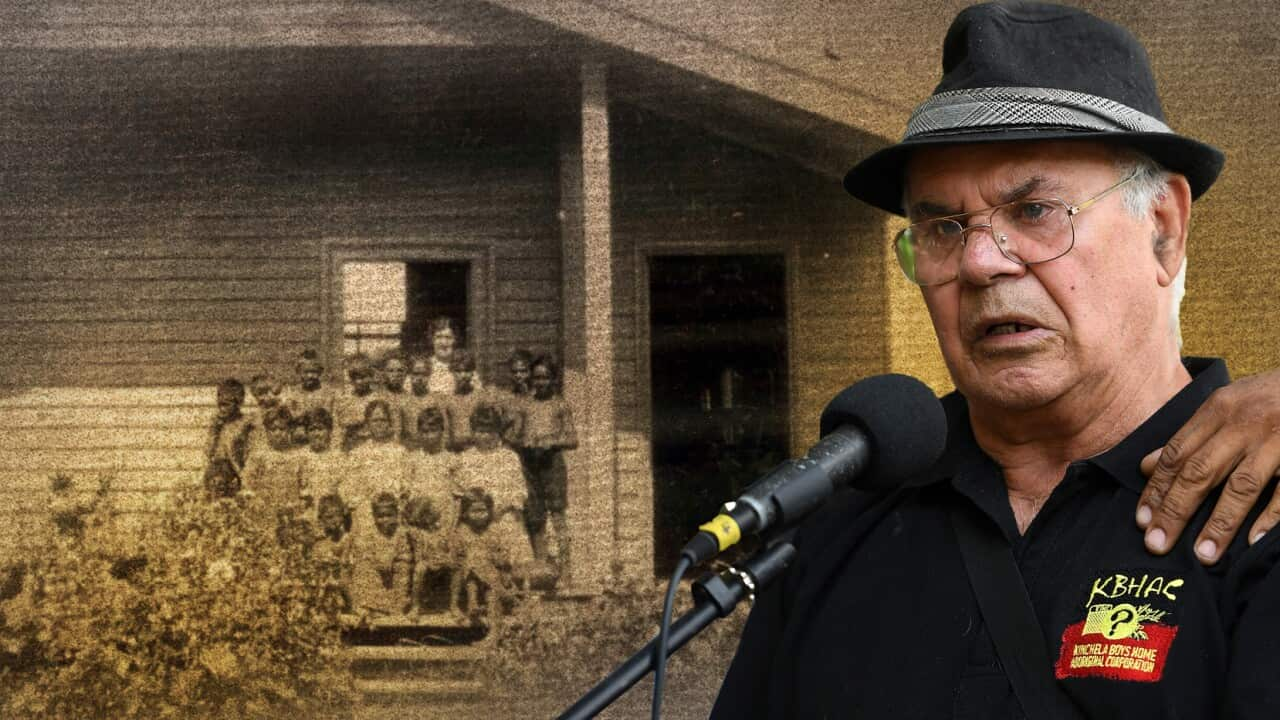

The Kinchela Aboriginal Boys Training Home was run by the New South Wales Government for over 50 years from the 1920s to the 1970s. Under the guidance of the so-called Aborigines Protection Act of 1909, the government forcibly removed boys aged five to 15 from their families and sent them to Kinchela. Source: Supplied / Kinchela Boys Home Aboriginal Corporation

Uncle Bobby Young says there were around 600 young boys like him who were stolen to be re-programmed to assimilate into white Australian society.

Now, there are 49 of them left.

"When you walked through the gates of hell, which is what we called it because it wasn't a happy place, it was sad. So there's going to be sad memories there when I get back there as well," he said.

'Boundaries and battles'

The Kempsey Aboriginal Land Council now owns the former Kinchela Boys Training Home.

The not-for-profit Aboriginal community-controlled organisation Kinchela Boys Home Aboriginal Corporation is allowed to use the site occasionally but is calling for ownership.

They are currently raising $10M to purchase the site, so they can create a centre for truth-telling and healing.

Taylor Fitzgerald says it would be a challenging weekend, but the community hopes to come together and celebrate survival.

"There's boundaries and battles that come with that, but really making sure that we're surviving through what has happened to us as people, not only just for our uncles. So it's going to be a really deadly weekend.

"There's going to be music, there's going to be dancing, there's going to be art, there's going to be kids activities. Just really promoting everything of what Kinchella Boys Home is as an organisation, but mainly supporting that truth-telling that our uncles do on a daily basis."

LISTEN TO

A group of First Nations Stolen Generations survivors retraces an emotional journey

SBS News

18/10/202405:12

Survivor, Uncle Willie Leslie, says he's looking forward to visiting the site.

"I'm looking forward to it, really looking forward to it. It's a nice area. I love it."

A place of healing for future generations

Fitzgerald says the act of starting the trip from Central Station is significant as it reflects the journey the men were forced to make as children.

"Of course, our uncles, in part of their truth-telling, they say that Central Station has such a massive impact as a lot of the time that this is where their story or their personal experiences started taking that journey to be placed into that boys' home.

"And then, of course, some uncles talk about how being dumped here after that and then just with all that trauma and impact and then having to make their own way."

Brian Shimadry from Transport for New South Wales says it's important that his department and the New South Wales government as a whole acknowledge its role in facilitating the Stolen Generations in order to move forward with healing.

"I think it's very important to acknowledge the trauma and pain that trains paid in part of the journey for Aboriginal people," he said.

"I think the trauma and intergenerational trauma that caused is something that Transport and New South Wales trains certainly want to work forward with reconciliation and continue to support our Aboriginal people and Aboriginal communities and our Aboriginal workforce."

A century after the opening of Kinchela Boys Home, survivors like Uncle Bobby Young would like to see Kinchela become a place of healing for future generations.

"What I would like to see happen is if we can get the site back, we want to turn it into a healing place museum and units and cafe," he said.

"And that there's [an] opportunity for our families, our grandkids, and our descendants so they can carry that future on for us."